History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

Wednesday, June 30, 2021

Governance at James Madison’s Montpelier

In fact, Madison appears to have been comfortable with that. He didn’t wrestle with the morality of slaveholding like his friend Thomas Jefferson. He didn’t even acknowledge the contradictions as frankly as Patrick Henry (“I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them. I will not—I cannot justify it, however culpable my conduct.”).

The historic site of James Madison’s Montpelier had been owned since 1983 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In 1998 the Montpelier Foundation was formed “with the goal of transforming James Madison's historic estate into a dynamic cultural institution.” Which of course means raising money.

More recently the Montpelier Descendants Committee formed as a “nonprofit organization devoted to restoring the narratives of enslaved Americans at plantation sites in Central Virginia, including but not limited to James Madison’s Montpelier.”

This month the Montpelier site announced a significant step in its governance, making the Descendants Committee and the Foundation co-equals in governing the historic site.

This is the latest step in a long process that included a National Summit on Teaching Slavery convened at Montpelier in 2018. One product of that gathering was the report “Engaging Descendant Communities in the Interpretation of Slavery at Museums and Historic Sites” (P.D.F. download).

Every historic site is in a different situation, but it will be interesting to see how other sites associated with slave-owning Founders approach the questions Montpelier has been talking through.

Tuesday, June 29, 2021

A Peek at Peale’s Mastodon

Ben wrote:

Exhumed in 1799 near the banks of the Hudson River and unveiled to the public on Christmas Eve, 1801, this was the very first mounted skeleton of a prehistoric animal ever exhibited in the United States. . . .The exhibit that includes this mastodon, which is actually about the scientist Alexander Humboldt, will be up at the Smithsonian American Art Museum only until 11 July.

After Peale’s Philadelphia museum closed in 1848, the mastodon was sold and wound up at the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, Germany. There it remained for over 170 years, largely forgotten in its home country, until SAAM senior curator Eleanor Harvey had the idea to include it in a new exhibition. . . .

I spoke to Advait Jukar, a Research Associate with the National Museum of Natural History, about his involvement with the mastodon. He inspected the skeleton in early 2020, shortly after it arrived in Washington, DC. As a fossil elephant specialist, Jukar was able to determine that the mastodon was an adult male, and that about 50% of the mount was composed of real, partially mineralized bone.

Fascinatingly, most of the reconstructed bones were carved from wood. This was the handiwork of Rembrandt Peale (Charles’ son), William Rush, and Moses Williams. Most of the wooden bones were carved in multiple pieces, which were locked together with nails and pegs. The craftsmanship is exquisite, and the joins are difficult to make out unless you stand quite close. The mandible is entirely wood, but the teeth are real. These teeth probably came from a different individual—one tooth on the right side didn’t fit properly and was inserted sideways!

The mastodon at SAAM differs from the original presentation at Peale’s museum in a few ways. The missing top of the skull was once modeled in papier-mâché, but this reconstruction was destroyed when the Landesmuseum was bombed during the second world war. It has since been remodeled in plaster.

While the mastodon was never mounted with real tusks, the mount has traditionally sported strongly curved replica tusks, more reminiscent of a mammoth. While Rembrandt Peale published a pamphlet in 1803 suggesting that the mastodon’s tusks should be positioned downward, like a pair of predatory fangs [shown above], it’s unclear if the tusks on the skeleton were ever mounted this way. At SAAM, the mastodon correctly sports a pair of nearly straight replicated tusks, which curve gently upward.

Monday, June 28, 2021

The Mystery of “Our Old Friend”

Most of the toasts that day were to people or historical events. Though the allusions could be stark—“Plume of Feathers. (August 26th 1346.)”; “The 1st of August 1759.”—Google and Wikipedia offered up explanations.

At first I thought “Our old friend” was the same sort of allusion, but I couldn’t find a standard explanation for it. When I searched for other examples of a toast to “Our old friend,” they almost always also named a specific old friend.

I found two exceptions to that pattern, which left me suspecting that the phrase was an inside joke, and perhaps a dirty one.

First, in the book Monstrous Good Songs, Toasts & Sentiments, for 1793, published in London by J. Parsons for sixpence, the very last toast in the book is:

Our old friend, and her worthy companion Thomas.

Second is an anecdote from The New Bon Ton Magazine, or Telescope of the Times, in 1818. That appears to have been a lads’ mag for its era, and its story was:

AMONGST our convivial customs at table, one stands mainly prominent, which is drinking a certain toast immediately upon the ladies’ retiring. We give it many designations, “Our old friend” being the most common.Alternative explanations welcome.

At a meeting of Bon Ton in the City of Edinburgh, when the ladies had retired, the honorable and beautiful Miss Elphinston being the last, she heard the chairman give a toast, “Here’s to what the ladies carried out with them.”

When the gentlemen assembled in the tea-room, she with true simplicity and artless innocence, asked Colonel [John] Anstruther [shown above], “Pray what did you mean by that toast given just as we went out; we took nothing out with us; I’m sure I had only my work-bag in my hand.”

“It was your work-bag we toasted,” said the Colonel, “from mere whim and humour, as being the work of so accomplished a young lady.”

To this day in Edinburgh the first toast after the ladies retire is

“Miss ELPHINSTON’S WORK-BAG.”

M.B.

Sunday, June 27, 2021

Visiting the American Republics

For The New Criterion, Daniel N. Gullotta of Stanford and the Age of Jackson podcast wrote:

Taylor’s history incorporates Canadian, Mexican, and Native American perspectives to recount the birth of the early Republic and the rise of American democracy. Taylor’s sources, which also include material from European diplomats and foreign travelers, offer unique insights on episodes routinely covered in similar books. International events loom particularly large in the mind of his antebellum American subjects, such as the establishment of Haiti as a free black republic in 1804, the various Latin American revolutions that erupted throughout the early nineteenth century, and the United Kingdom’s Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.The Washington Post commissioned its review from Colin Woodard, author of American Nations and Union and journalist at the Portland Press Herald:

While other works have shown how involved Americans were in regional events and national politics, Taylor demonstrates their keen awareness of foreign events and global changes, too. They were, for instance, angry that Canadians and Britons thought of the United States as a nation of irresponsible drunks, ill-tempered ruffians, and hypocritical slavers. . . .

Even the Americans who did want to expand the nation’s borders rarely did so out of a national sense of shared destiny, but rather out of regional self-interest. The absence of early American nationalism in this period might surprise readers, who will find more figures proudly willing to call themselves Virginians, Georgians, or New Yorkers than Americans. This regionalism and the issue of slavery made for a young nation full of anxiety and built on fragile alliances, ready to break out into civil war at almost any moment.

The takeaway is that this era of conquest and expansion was a time of anguish and acrimony for U.S. leaders — manifest uncertainty — and terrible tragedy for many of the continent’s inhabitants. In an effort to achieve security for its White citizens — to protect them from imperial rivals, native nations and enslaved-person uprisings — the United States aggressively expanded. The effort instead triggered the Civil War, as the balance of power between slave and free states became impossible to maintain. . . .In addition, Taylor did a podcast interview with Lewis Lapham.

For Americans used to the comforting myth of an exceptional union boldly leading humanity in a better direction, this account may sting. Taylor doesn’t seek to salve such pain, but neither has he written a polemic. Diligently researched, engagingly written and refreshingly framed, “American Republics” is an unflinching historical work that shows how far we’ve come toward achieving the ideals in the Declaration — and the deep roots of the opposition to those ideals.

Saturday, June 26, 2021

The Latest on the Adams Academy

As I reported then, it took decades for the Adams Academy to be built, and it never actually housed Adams’s books. Those books were sent to the new Boston Public Library in 1893, an act widely reported as a “gift” from the city of Quincy.

After the academy closed, other organizations used its stone building, most recently the Quincy Historical Society. The Adams Temple and School Fund remained, eventually charged with benefiting a nearby school. The city’s management of those assets became a subject of litigation in this century, and eventually the courts told Quincy to pay the school $2 million.

What prompted my posts was a proposal by Quincy mayor Thomas Koch to turn the Adams Academy building into a John Adams Presidential Library. Not the type of presidential library that houses a former President’s papers, since those are at the Massachusetts Historical Society, but Mayor Koch did ask the Boston Public Library to send back Adams’s books.

My South Shore friend Patrick Flaherty just sent me a Quincy Patriot Ledger article reporting the latest developments in this story. In December the Massachusetts court system ruled that the Adams Academy is the property of the Adams Temple and School Fund, not the city of Quincy. That fund’s trustee thus had the legal right to sell the building and land for the benefit of the surviving school.

Mayor Koch then announced that Quincy would exercise its power of eminent domain, buying the Adams Academy and two nearby properties for a “fair market price.” The city’s most recent assessments of the three buildings total to almost $4.1 million. However, since the neighboring properties were going to be redeveloped into larger buildings containing more than sixty residences, that could well affect their market value.

The Quincy city council’s finance committee just approved a plan, already approved by the Community Preservation Commission, to spend $9 million from the Community Preservation Act to settle the lawsuit, buy the three properties, and presumably pay legal fees. The immediate goal appears to be preventing that development around the academy building. What will become of the building is still up in the air.

The city’s current plan, which still needs a full council vote, doesn’t cover the creation of a presidential library. Not all the councilors who approved spending the $9 million are on board for spending more on that idea. For his part, the mayor told the newspaper, “I don’t expect to build that with city money.”

Friday, June 25, 2021

Founders Feeling Homesick—and Using That Word

I was relying on Etymology Online, but that turns out to be mistaken.

The Oxford English Dictionary states that “homesick” first appeared in 1748 in a collection of Moravian Brethren hymns printed in London. That word was a direct translation of the German “heimweh.”

Likewise, the earliest appearance of “homesickness” in 1756 was a direct translation of “heimweh” in an edition of the travel writings of Johann Georg Keyssler.

One might assume the word was still working its way into English at that time, starting in the imperial capital. But I came across an example of the word being used in a remote corner of the British Empire. On 2 Dec 1756, none other than Col. George Washington reported to Gov. Robert Dinwiddie about provincial conscripts under his command:

I have used every endeavour to detain the Drafts, but all in vain. They are home-sick, and tired of work.The young colonel wrote from Fort Loudoun (recreation shown above) in what in now south-central Pennsylvania. He obviously expected his superior to understand the word.

In addition (and this example is noted in the O.E.D.), in November 1759 Gen. Jeffery Amherst wrote in his journal: “As soon as the homesick were getting in the boats they were immediately half recovered.”

The second appearance of “home-sick” listed in the O.E.D. is from the journal of Philip Vickers Fithian on 21 Nov 1773. By that point some familiar correspondents were also using the term:

- Benjamin Franklin to his son William, 30 Jan 1772: “I have of late great Debates with my self whether or not I should continue here any longer. I grow homesick, and being now in my 67th. Year, I begin to apprehend some Infirmity of Age may attack me, and make my Return impracticable.”

- Franklin to Jonathan Shipley, June 1773?: “But I grow exceedingly homesick. I long to see my own Family once more. I draw towards the Conclusion of Life, and am afraid of being prevented that Pleasure.”

- Abigail Adams to John, from Weymouth, 30 Dec 1773: “The Time I proposed to tarry has Elapsed. I shall soon be home sick. The Roads at present are impassible with any carriage. I shall not know how to content myself longer than the begining of Next week.”

We see that idea reflected in the way John Adams wrote of his own homesickness on 28 Mar 1783.

- To Abigail: “No Swiss ever longed for home more than I do.”

- To C. W. F. Dumas: “No Swiss was ever more homesick than I am.”

Thursday, June 24, 2021

More to See at History Camp America 2021

There are seven more video previews of sessions at this page, ranging from Fort Ticonderoga in the north to the Buffalo Soldier National Museum in ths south.

Here are more scheduled History Camp America sessions with some link to Revolutionary New England:

- Video tour of Fort Ticonderoga

- Video tour of Buckman Tavern in Lexington

- “Reimagining America: The Maps of Lewis and Clark” by Carolyn Gilman

- “The Amphibious Assault on Long Island August 1776” by Ross Schwalm

- “Saunkskwa, Sachem, Minister: native kinship and settler church kinship in 17th and 18th-century New England” by Lori Rogers-Stokes

- “‘Thrown into pits’: how were the bodies of the nineteen hanged Salem ‘witches’ really treated?” by Marilynne K. Roach

- “Black Flags, Blue Waters: The Epic History of America’s Most Notorious Pirates” by Eric Jay Dolin

- “Inconvenient Founders: Thomas Young and the Forgotten Disrupters of the American Revolution” by Scott Nadler

- “Slaves in the Puritan Village: The Untold History of Colonial Sudbury” by Jane Sciacca

- “Surviving the Lash: Corporal Punishment and British Soldiers’ Careers” by Don Hagist

- “Saving John Quincy Adams From Alligators and Mole People” by Howard Dorre

- “Lafayette’s Farewell Tour and National Coherence – The Lafayette Trail” by Julien Icher

- “Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern: The Headquarters of the Revolution” by Andrew Cotten

- “The Fairbanks House of Dedham: The House, The Myth, The Legend” by Stuart Christie

- “First Amendment Origin Stories & James Madison Interview” by Jane Hampton Cook & Kyle Jenks

- “Historic Marblehead – A Walking Tour” by Judy Anderson

- “The Second Battle of Lexington & Concord: re-inventing the history of the opening engagements of the American Revolution” by Richard C. Wiggin

- “To Arms: How Adams, Revere, Mason, and Henry Helped to Unify their Respective Colonies” by Melissa Bryson

Again, registration costs $94.95, and for another $30 folks can receive a box of goodies from History Camp sponsors and participating historical sites. Registrants can watch videos and participate in scheduled live online discussions on 10 July, and will have access to the entire video library for a year.

Wednesday, June 23, 2021

A Preview of History Camp America 2021

Via Vimeo, here’s a preview of my video presentation “Washington in Cambridge and the Siege of Boston” prepared for History Camp America 2021, an online event coming up on 10 July.

I’ve presented at History Camp Boston since its beginning and at a couple of Pioneer Valley History Camps as well. They’re fun events that bring together academic historians, public historians, living historians, independent historians, and unabashed history buffs (often overlapping categories) to learn about all sorts of topics and research.

Unfortunately, for the last two years the Covid-19 pandemic has made large public get-togethers risky. In 2020 the History Camp organizing team produced America’s Summer Road Trip instead.

This year, the team invites people to register for History Camp America, gaining access to over two dozen video presentations covering a wide range of subjects (listed here). Registration costs $94.95, and for another $30 folks can receive a box of goodies from History Camp sponsors and participating historical sites. Households who register can watch videos and participate in scheduled live online discussions on 10 July, and they’ll have access to the entire video library for a year.

When I first thought about presenting at History Camp America, I pictured another live Zoom talk. But we’ve seen a lot of those, right? Then Lee Wright of History Camp and I developed a way to take better advantage of the video format by recording segments at more than half a dozen historical sites linked to Gen. George Washington’s mission in Massachusetts in 1775 and 1776.

We still have stuff to learn about making such videos, from wardrobe choice and collecting good sound next to traffic to remembering which of the four lessons I talk about is number two. But overall I’m pleased with the way this video turned out. I’ll tune in on 10 July to offer commentary and answer questions in the session chat room. I hope you folks will join me!

Tuesday, June 22, 2021

The Regimental Goat and “Memory Creep”

As one writer picks up a story from another, he or she can change it slightly—either through error or through wishfully reading sources in a more dramatic or meaningful way. And then the next writer changes it further. The earliest sources can get buried or stay hovering in brief quotations or citations, lending an air of reliability, when in fact they don’t say what the latest writer says they said.

Thus, a man who was serving in the provincial army during Bunker Hill becomes a soldier who fought in the battle—even if he was stationed on the other end of the siege lines. A man turning out for several short-term militia activations over the course of the war becomes a Continental soldier who served the length of the war. A plausible but undocumented travel route gets marked with stones and steel signs that seem beyond doubt.

In the case of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, the British casualty lists after the Bunker Hill battle included many officers from the flank companies of that 23rd Regiment, but none from the other companies. For decades authors assumed that all the companies suffered losses at the same rate but some records weren’t available. That made the American fire more effective, the regiment’s sacrifice more gallant—both sides won.

In fact, British army sources were very good at reporting the names of all killed and wounded officers. (Enlisted men, not so much.) The less dramatic but more accurate interpretation of the evidence is that the rest of the 23rd Regiment’s companies just didn’t fight in that battle.

Likewise, the solid evidence that by 1775 the 23rd Regiment was in the habit of “passing in review preceded by a Goat” became a picture of the regiment marching into battle on 17 June 1775 behind that goat. That’s a very striking picture which can be hard to resist once one thinks of it.

That sight should also have been striking to the men who fought that battle, especially the provincials. Yet no eyewitness ever reported seeing a goat on the field, much less one leading a redcoat company or butting its way into the redoubt. Left without supporting evidence, authors quoted James Fenimore Cooper’s otherwise-unread novel for support, even though his character didn’t even say the goat was in the battle.

Significantly, claims that the Royal Welch Fusiliers marched into the fight behind a goat appear almost exclusively in books and articles about the regiment. It’s a claim that requires good evidence and comes with little to none. I haven’t found a single mention of the animal in books about the Battle of Bunker Hill.

In 1777 a British officer, Maj. Robert Donkin, set down a story that the regimental goat had bucked off its rider at the 1775 St. David’s Day dinner. A version of that anecdote was reprinted many times in the nineteenth century. But for one train of authors, the story became more meaningful after they interpreted Donkin’s words to mean that the the rider had died. That made a comic moment into something portentous. But no drummer was actually killed in the making of that anecdote.

I can’t trace the story of the Royal Welch Fusiliers adopting a “wild goat” on the Bunker Hill battlefield the same way, but I think it arose in recent years through the same process. Someone saw that the historical record of the regiment’s goat goes back only to 1775, and claims that a goat led the Fusiliers at Bunker Hill, and put those ideas together to create an entertaining story: The 23rd adopted their first goat on the Bunker Hill battlefield!

Again, the historical sources actually say the Royal Welch Fusiliers was known for parading with a goat before 1775, even if no one had bothered to write it down. But no one testified to seeing a goat, wild or saddled or gilt-horned, during the Battle of Bunker Hill. The mascot of the 23rd Regiment must have sat out the battle in Boston with most of the Fusiliers. The real question is how it survived the hungry weeks of the siege that followed.

Monday, June 21, 2021

“A poor drum-boy, killed by the goat on St David’s Day”

In describing that regiment’s losses at the Battle of Bunker Hill, the writer said:

If it may be permitted to quote a work of fiction as an authority, it may be observed, as a confirmation of the severe loss of the regiment, that an American novelist, after describing the battle of Bunker’s Hill, states, “The Welsh Fusileers had not a man left to saddle their goat.”The article didn’t name the American novelist (though, to be fair, there weren’t that many back then, so it was a lot easier to guess). It also didn’t explain the goat. Apparently readers of this magazine were supposed to know.

Eighteen years later, in 1850, the British military clerk Richard Cannon (1779-1865) borrowed that sentence for a footnote in the Historical Record of the Twenty-Third Regiment that he’d been assigned to compile. Cannon identified the source of the line as “J. Fennimore [sic] Cooper, in his work entitled, ‘Lionel Lincoln’.” Cannon also quoted from Francis Grose quoting from Maj. Robert Donkin to explain the goat.

Another thirty-nine years later, in 1889, a reviewer in the United Service Magazine (the latest name for the United Service Journal) criticized Cannon for using such “apocryphal sources of information” as Cooper‘s fiction and a letter from Abigail Adams setting down rumors. That critic pointed out that the 23rd Regiment’s records show that only the grenadier and light infantry companies were ordered onto Bunker Hill. Most of the Royal Welch Fusiliers stayed on the Boston side of the river and suffered no casualties.

But by then the idea that the Royal Welch Fusiliers had lost so many men they couldn’t even saddle their goat had moved from a remark by a character in an American novel into an official British military history.

And that wasn’t the only elaboration. In Famous Pets of Famous People (1892), Eleanor Lewis cited “an officer [who] wrote at some length in the London Graphic” as quoting the description of the 1775 St. David’s Day in Francis Grose’s Military Antiquities and adding:

the same goat which threw the drummer accompanied the regiment into action at Bunker’s Hill, when the Welsh Fusileers had all their officers except one placed hors de combat. What became of the Bunker’s Hill goat, we do not know; nor can we say how many successors he had between the years 1775 and 1844.That same year, an article in The Cornhill Magazine titled “A Wreath of Laurels” offered another variation on the sources from the 1770s:

The death of a poor drum-boy, killed by the goat on St David’s Day, just before the outbreak of the American War, must have seemed an omen of the disaster of ‘Bunker's Hill,’ when, according to Fennimore Cooper, ‘the Welsh Fusiliers had hardly men enough left to saddle their goat.’This author cited Richard Cannon’s regimental history about the death of the drummer. In fact, Cannon had simply quoted the report of the goat bucking the drummer onto a table. No source mentioned any children killed at that dinner, and that’s the sort of detail people mention.

Given such exaggeration, it was relatively restrained for The Navy and Army Illustrated to state on 12 Nov 1898: “At any rate, we know that the regiment had a goat with them at Bunker’s Hill in 1775.”

But do we know that?

TOMORROW: Wrapping up the goat story.

[The photograph above comes from the 1898 story in The Navy and Army Illustrated.]

Sunday, June 20, 2021

“Hardly men left enough to saddle their goat!”

Grose, a hard-working if not particularly talented draftsman, published four volumes of images of Britain’s medieval ruins from 1772 to 1776.

As a result, Grose had to publish a lot more books in the years after the war. In addition to more sketchbooks, he came out with his oft-cited Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785) and A Provincial Glossary, with a Collection of Local Proverbs, and Popular Superstitions (1787).

Grose also drew on his military experience. In 1783 he was the anonymous author of Advice to the Officers of the British Army, an acerbic satire on how the army operated in the recent war. And in 1786 he collected stories from many sources into Military Antiquities Respecting a History of the English Army.

One of those sources was Maj. Robert Donkin’s Military Collections and Remarks. In a footnote on pages 265-6 of his 1788 London edition, Grose quoted (though inexactly) what Donkin’s book said about the Royal Welch Fusiliers, their gilt-horned goat, and the disrupted St. David’s Day dinner of 1775. Grose’s reprinting of that anecdote ensured it remained available to readers into the next century even when Donkin’s book became rare.

In 1818 Samuel Swett published his first essay on the Battle of Bunker Hill as an appendix to an edition of David Humphreys’s short biography of Gen. Israel Putnam. In a footnote he provided a somewhat garbled explanation of the 23rd Regiment’s goat tradition:

From a tradition that a former Prince of Wales had ridden from his principality into England on a goat; a very large one, with gilded horns, was always maintained by the corps, and they celebrated the anniversary of the feat by a procession, rejoicing and exultation.As the sources from the 1770s indicate, the fusilier officers observed St. David’s Day, but perhaps this was how some old Bostonians understood the ritual.

The next figure in the spread of 23rd Regiment goat lore was James Fenimore Cooper, the New York novelist. Three of his first five books—the three that were most successful—were stories of eighteenth-century America. Cooper made a plan to write thirteen more novels about the Revolution, using actual historical figures and events, one for each original state in the union.

The first of those books was Lionel Lincoln, or The Leaguer of Boston, published in 1825 to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of war. Cooper put a lot of effort into depicting historical events such as the Battle of Bunker Hill, but the plot was his usual overcooked melodrama. That might not have been a problem except that for some reason Cooper thought that his public wanted to read about an aristocratic Loyalist antihero.

Lionel Lincoln was a critical and sales failure, and remains so to this day. Cooper abandoned his plan to write more books like that. His next novel was The Last of the Mohicans.

In Lionel Lincoln one character discussing the British casualties at Bunker Hill says: “the Fusileers had hardly men left enough to saddle their goat!” Cooper then showed off his research with a footnote:

This regiment, in consequence of some tradition, kept a goat, with gilded horns, as a memorial. Once a year it celebrated a festival, in which the bearded quadruped acted a conspicuous part. In the battle of Bunker-Hill, the corps was distinguished alike for its courage and its losses.Cooper probably relied on Grose’s Military Antiquities or Swett’s footnote, or both, for his information, which is notably vague on the particulars. Either way, it’s clearly an allusion to how the Royal Welch Fusiliers celebrated, not how they entered battle.

But that’s not how people chose to read it.

TOMORROW: Putting a goat on the battlefield.

Saturday, June 19, 2021

“Mounted on the goat richly caparisoned for the occasion”

In 1772 Capt. Donkin married Mary Collins, daughter of a clergyman. They had their first child, a son they named Rufane Shaw Donkin, in early October, with two daughters to follow.

Then came the American War. In 1775 Donkin was assigned to the Royal Welch Fusiliers, or 23rd Regiment. He was one of the officers present at the regiment’s St. David’s Day dinner on 1 March reported yesterday.

By 1777 Donkin held the rank of major in the 44th Regiment of Foot, stationed in New York City. He decided that was the right time and place to publish what he called a “collection and remarks of a late general officer of distinguished abilities, in the science of war, in every possible situation of an army.” That probably meant Gen. Rufane, who had died in 1773. Donkin supplemented that collection with his own material.

The major collected £290 in subscriptions, mostly from his fellow officers. He stated that he “published for the benefit of the children and widows of the valiant soldiers inhumanly and wantonly butchered when peacefully marching to and from Concord, April 19, 1775, by the rebels.”

Donkin made a deal with Hugh Gaine (1726-1807), a Belfast-born printer who had supported the Patriot cause in his New-York Mercury newspaper until late 1776. Then Gaine had decided the British would probably win, slipped back into the occupied city, and resumed publishing his paper with a new editorial slant.

Donkin’s Military Collections and Remarks offered a livelier description of the 1775 St. David’s Day dinner:

The royal regiment of welch Fuzileers has the privilegeous honor of passing in review preceded by a Goat with gilded horns, and adorned with ringlets of flowers; and although this may not come immediately under the denomination of a reward for Merit, yet the corps values itself much on the ancientness of the custom.Donkin’s text thus explains that mysterious sentence from the Boston News-Letter article on this event: “St. David, mounted on a Goat, adorned with Leeks, presented himself to View.” A young drummer played the part of St. David while riding on a goat. (A goat who, on this date, didn’t want to be ridden.)

[Footnote:] Every 1st of March being the anniversary of their tutelar Saint, David, the officers give a splendid entertainment to their welch brethren; and after the cloth is taken away, a bumper is filled round to his royal highness the Prince of Wales, (whose health is always drunk the first that day) the band playing the old tune of, “The noble race of Shenkin,” when an handsome drum-boy, elegantly dressed, mounted on the goat richly caparisoned for the occasion, is led thrice round the table in procession by the drum-major.

It happened in 1775 at Boston, that the animal gave such a spring from the floor, that he dropped his rider upon the table, and then bouncing over the heads of some officers, he ran to the barracks with all his trappings, to the no small joy of the garrison and populace.

These sources from the Revolutionary years show that the claim I quoted back here, that the Royal Welch Fusiliers adopted a “wild goat” that trotted onto the Bunker Hill battlefield, to be bunk. The regiment already had “a Goat with gilded horns” months and probably years before the battle.

As for Maj. Donkin, he continued serving in the British army. In 1778 he put his son, then aged five, on the roster of the 44th Regiment as an ensign, and the following year promoted him to lieutenant. Meanwhile, the boy was studying at the Westminster School in London.

Donkin became lieutenant colonel in charge of the Royal Garrison Battalion from 1779 to 1783, then colonel in 1790, major general in 1794, lieutenant general in 1801, and general in 1809. The picture above shows him in the Pump-Room at Bath in 1809. Donkin died in Bristol in 1821. By then his son was a decorated major general and acting governor of the Cape Colony.

TOMORROW: How the goat story bounced.

Friday, June 18, 2021

“St. David, mounted on a Goat”

In his entry for 1 Mar 1775, Lt. Mackenzie described how the regiment’s officers organized a festive dinner in honor of St. David’s Day. David was the patron saint of Wales, and even though the 23rd’s no longer had a particular connection to Wales beyond its name, that was enough of an excuse for a feast at the end of winter.

Mackenzie listed the men who dined at this event, both from the 23rd Regiment and from the wider garrison. Generals Thomas Gage and Frederick Haldimand came, along with brigadiers Earl Percy and Valentine Jones. (Gen. Robert Pigot was invited but “was unwell.”) Adm. Samuel Graves represented the Royal Navy. Many top staff officers attended, as did the regimental surgeon and chaplain. Two officers “Formerly in the Regt.” and two designated only as “Welchmen” were additional guests.

Unfortunately, about the festivity itself Mackenzie wrote nothing beyond that it was “according to Custom.” For more information we turn to the report printed in Margaret Draper’s Boston News-Letter the next day:

Yesterday being DAVID’s Day, (the Tutelar Saint for Wales,) the same was observed with the usual demonstrations of Joy, by his Majesty’s own Regiment of Royal Welch Fusilears; an elegant Entertainment was provided at the British Coffee-House, which his Excellency the Commander in Chief honored with his Presence: The Admiral and all the General Officers likewise assisted.---I’ve used links to annotate the historical allusions in those toasts.

On entering the Room, St. David, mounted on a Goat, adorned with Leeks, presented himself to View, and the whole Ceremony concluded with the following Healths:—

1. St. DAVID and Wales.

2. Prince of Wales.

3. The KING.

4. The QUEEN and Royal Family.

5. The General and the Army.

6. The Admiral and the Navy.

7. Lord NORTH.

8. Lord Dartmouth.

9. Plume of Feathers. (August 26th 1346.)

10. Colonels and Corps.

11. The glorious Memory.

12. Our old Friend.

13. The 1st of August 1714. (Hanover Succession.)

14. The 1st of August 1759. (Minden.)

15. The 13th of September 1759. (Quebec.)

16. The 20th of November 1759. (Hawke.)

17. May Great-Britain forever maintain her Supremacy over the Colonies.

18. The 1st of July 1690. (Boyne.)

19. The 12th of July 1691. (Aghrim.)

20. The 15th of of April 1746. (Culloden.)

21. General Amherst, and the 8th of September 1760. (Surrender of Canada.)

22. Prince Ferdinand.

This newspaper item offers what appears to be the earliest record of a goat associated with the Royal Welch Fusiliers: “St. David, mounted on a Goat, adorned with Leeks, presented himself to View.” The article doesn’t make clear what that means—evidently the right people were supposed to know already, indicating that this was an established tradition.

For more detail, we must turn to another officer’s account of that same dinner.

TOMORROW: Goat behaving badly.

Thursday, June 17, 2021

A Goat from Bunker Hill?

Was there a goat at the Battle of Bunker Hill?

In the first decade of this century the Royal Welch battalion of the British army, successor to the Royal Welch Fusiliers or 23rd Regiment of the eighteenth century, had a goat mascot named William Windsor. Naturally, he has his own Wikipedia page, which explains:

The tradition of having goats in the military originated in 1775,[2] when a wild goat walked onto the battlefield in Boston[2] during the American Revolutionary War and led the Welsh regimental colours at the end of the Battle of Bunker Hill.[3][4]Look at all those citations! Of course, most of them are to 2009 newspaper articles about William Windsor’s retirement to a zoo. Others lead to the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum.

That museum offers a P.D.F. file listing all the goat mascots, but it goes back only to 1844. Those are all the “royal goats,” however, presented to the unit by Queen Victoria and her successors. There’s good evidence that the Royal Welch Fusiliers found their own goats before that.

But as to whether the 23rd adopted a wild goat on the Charlestown battlefield, for that we need primary sources, right?

TOMORROW: Voices from 1775.

(The photograph above comes from the B.B.C.’s report on the death of a more recent Royal French battalion mascot called Lance Corporal Shenkin II.)

Wednesday, June 16, 2021

A British Soldier Debilitated by Nostalgia in 1781

In July 1780 Hamilton, a weaver’s son just out of medical school, was commissioned a surgeon’s mate for the British army’s 10th Regiment of Foot. That regiment had been involved in the very beginning of the Revolutionary War, its light company firing at militiamen on Lexington common. But in 1778 the depleted 10th was sent back to Britain to rebuild.

Hamilton’s case study reported on a young man enlisted in those years:

In the year 1781, while I lay in barracks at Tinmouth in the north of England, a recruit who had lately joined the regiment (named Edwards), was returned in the sick list, with a message from his captain, requesting I would take him into the hospital.Hamilton first suspected “an incipient typhus” and started treatment for that disease. But this private didn’t improve. He barely ate, spent most of his time dozing in bed. After “near three months” in the hospital, he looked “like one in the last stage of a consumption.”

He had only been a few months a soldier; was young, handsome, and well-made for the service; but a melancholy hung over his countenance, and wanness preyed on his checks. He complained of universal weakness, but no fixed pain; a noise in his ears, and giddiness of his head. Pulse rather slow than frequent; but small, and easily compressible. His appetite was much impaired. His tongue was sufficiently moist, and his belly regular; yet he slept ill, and started suddenly out of it, with uneasy dreams. He had little or no thirst.

As there were little obvious symptoms of fever, I did not well know what to make of the case.

Fortunately, there was a nurse at the hospital paying attention to the whole patient. Dr. Hamilton wrote:

she happened to mention the strong notions he had got in his head, she said, of home, and of his friends. What he was able to speak was constantly on this topic. This I had never heard of before. The reason she gave for not mentioning it, was, that it appeared to her to be the common ravings of sickness and delirium. He had talked in the same style, it seems, less or more, ever since he came into the hospital.The recruit asked the doctor if he could go home. Hamilton replied that he was in no physical shape to travel. But, even without the commanding officer’s approval, he promised a six-week furlough if the soldier could recover.

I went immediately up to him, and introduced the subject; and from the alacrity with which he resumed it (yet with a deep sigh, when he mentioned his never more being able to see his friends), I found it a theme which much affected him.

“In less than a week,” Dr. Hamilton reported, he saw “evident signs of recovery.” The young man was in a better mood. At first he enjoyed being carried out to the beach to watch the ships. In less than two months, the private was able to walk to his barracks.

Dr. Hamilton then set about getting the soldier that furlough. He convinced the regiment’s officers that their recruit would relapse if he wasn’t allowed to see home again. Finally, the commanding officer “obligingly granted” a leave. And there the story ended.

Hamilton reprinted his essay in 1787 and again in 1794 in The Duties of a Regimental Soldier. Philip Shaw analyzed that version in the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies in 2014, noting at the end:

Although the muster rolls for the 10th Foot Regiment list a soldier named John Edwards as sick for consecutive periods in 1780 when the regiment was stationed in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, there is no mention of a soldier with this name in the sick list for Tynemouth in 1781, which is the place and year that Hamilton establishes.Hamilton’s case study used the name “Edwards” only once, and in parentheses. In his book, the doctor also referred to another soldier with a different problem by the same name. Finally, Shaw adds that a sad army veteran named Edwards was a character in Henry Mackenzie’s popular 1771 novel A Man of Feeling. So it’s likely that Edwards was not the soldier’s real name—or that Hamilton wasn’t exact in other details.

Be that as it may, Hamilton made a point of his patient being from Wales. That was on the other side of Britain from Newcastle or Tynemouth, a significant distance. In addition, Wales is a mountainous region, and at the time people from the Alps were thought to be especially prone to nostalgia, perhaps because of altitude changes.

As for any possible connection between nostalgia and post-traumatic stress disorder, this is another case of a man showing signs of depression before seeing any known combat. Hamilton obviously viewed the problem as homesickness, though of course this young man might have been naturally melancholic.

(The photograph above is a detail of an image from Newcastle Photos showing Tynemouth Castle and Priory, used for barracks over the centuries. I’m not sure that Dr. Hamilton and Pvt. Edwards were housed there, but it looks handsome.)

Tuesday, June 15, 2021

Nostalgia “a frequent disease in the American army”

American doctors did use the diagnosis of nostalgia, learning it from European medical authorities. Their uses reflected the original meaning of the word as homesickness rather than how we use the term today.

In “An Account of the Influence of the Military and Political Events of the American Revolution upon the Human Body” (published with other essays in 1789), Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote:

THE NOSTALGIA of Doctor [William] Cullen, or the homesickness, was a frequent disease in the American army, more especially among the soldiers of the New-England states. But this disease was suspended by the superior action of the mind under the influence of the principles which governed common soldiers in the American army.Rush’s essay was as much political as medical. He wanted to make the case that, while the disruptions of revolution and war caused stress and illness, the best remedy was more republicanism. Nothing cured the New Englanders’ nostalgia quicker than the imminent prospect of being hanged as traitors by an invading monarchical army.

Of this General [Horatio] Gates furnished me with a remarkable instance in 1776, soon after his return from the command of a large body of regular troops and militia at Ticonderoga. From the effects of the nostalgia, and the feebleness of the discipline, which was exercised over the militia, desertions were very frequent and numerous in his army, in the latter part of the campaign; and yet during the three weeks in which the general expected every hour an attack to be made upon him by General [John] Burgoyne, there was not a single desertion from his army, which consisted at that time of 10,000 men.

Rush’s memory may have been faulty about dates. He said Gen. Gates told him in 1776 that nostalgia cleared up because of the threat from Gen. Burgoyne. In that year, Gen. Guy Carleton was in command, with Burgoyne serving under him. Burgoyne led the bigger advance from Canada in 1777. Rush may have amalgamated the events in his mind, but such detail doesn’t matter much to how Rush understood nostalgia.

Dr. James Thacher of Plymouth served the entire war as a surgeon’s mate and military surgeon for the Continental Army. Decades later, in 1823, he adapted his wartime diaries into A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War.

In that book Thacher wrote under the date of late June 1780:

Our troops in camp are in general healthy, but we are troubled with many perplexing instances of indisposition, occasioned by absence from home, called by Dr. Cullen nostalgia, or home sickness. This complaint is frequent among the militia, and recruits from New England. They become dull and melancholy, with loss of appetite, restless nights, and great weakness. In some instances they become so hypochondriacal as to be proper subjects for the hospital.Rush and Thacher didn’t use the term “nostalgia” in a way that we can easily map onto the modern diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Thacher definitely saw signs of anxiety and depression with physical manifestations. Rush linked the condition to desertions. But they didn’t see nostalgia as a reaction to combat.

This disease is in many instances cured by the raillery of the old soldiers, but is generally suspended by a constant and active engagement of the mind, as by the drill exercise, camp discipline, and by uncommon anxiety, occasioned by the prospect of a battle.

Both of these doctors described nostalgia as prevalent in soldiers away from home (particularly from New England), not in those soldiers who had been through hard fighting. In fact, both of these American doctors saw “the prospect of a battle” as dispelling nostalgia, and Thacher viewed “old soldiers” as less prone to it than fresh militiamen.

It’s possible that other American doctors diagnosed Revolutionary soldiers or veterans with nostalgia based on symptoms and circumstances that correspond better with what we call P.T.S.D. I’ve looked for such cases, haven’t found any, and would welcome references.

TOMORROW: A British case study.

Monday, June 14, 2021

A Mistaken Idea of Nostalgia’s Origin

The symptoms of this condition, Hofer wrote, included:

continued sadness, meditation only of the Fatherland, disturbed sleep either wakeful or continuous, decrease of strength, hunger, thirst, senses diminished, and cares or even palpitations of the heart, frequent sighs, also stupidity of the mind—attending to nothing hardly, other than an idea of the FatherlandThe young doctor medicalized (and Hellenized) a condition that his fellow German-speaking Swiss were already calling Heimweh.

Over the next few decades other Swiss physicians wrote about the same condition. Some of them described spotting those symptoms in Swiss soldiers working far from home as mercenaries. They debated causes, with J. J. Scheuchzer (1672-1733) theorizing that the problem was the change in altitude from the Alps. No one appears to have blamed the experience of war, however.

Eventually the concept of nostalgia or Heimweh traveled to other European countries. It became mal du pays in French-speaking Switzerland and then France, listed in a French medical manual by 1754.

The word “homesickness” appeared in English in 1756, just a little too late for Dr. Samuel Johnson’s dictionary. The Scottish physician and professor William Cullen (1710-1790, shown above) eventually included two forms of nostalgia, simplex and complicata, in his Synopsis Nosologiae Methodicae. Again, doctors saw this problem arising from being away from home, not from experiencing trauma.

In the last decade of the eighteenth century, Revolutionary and Imperial France produced armies larger than Europe had ever seen, armies that swept across other countries as far as Moscow. When some of those soldiers began to demonstrate signs of anxiety and depression, and—what militaries most care about—stopped being able to fight, physicians looked for reasons. Nostalgia was one diagnosis they discussed, hypothesizing that the symptoms would disappear when the men returned home. Today we might instead suspect those soldiers were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Over the next century, nostalgia evolved to mean something separate from homesickness. It came to refer to yearning for another time more than another place. It became a cultural condition, not a psychological or physical malady. By 1975 the origin of the term was so obscure that George Rosen published a paper titled “Nostalgia: A ‘Forgotten’ Psychological Disorder” in Psychological Medicine.

I don’t have access to that paper, so I can’t assess how Rosen described the original characterization of the condition. Four years later Fred Davis wrote in A Sociology of Nostalgia:

Coined by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in the late seventeenth century, the term was meant to designate a familiar, if not especially frequent, condition of extreme homesickness among Swiss mercenaries fighting far from their native land in the legions of one or another European despot. The “symptoms” of those so afflicted were said by Hofer and other learned physicians of the time to be despondency, melancholia, lability of emotion, including profound bouts of weeping, anorexia, a generalized “wasting away,” and, not infrequently, attempts at suicide.As reported yesterday, Hofer’s dissertation defining nostalgia did not address “extreme homesickness among Swiss mercenaries.” His case studies involved civilians. Davis, and perhaps others before him, projected back from the interest in nostalgia among Swiss and later French military physicians in the 1700s to make soldiers part of the condition’s 1688 origin story, a crucial element of the diagnosis.

Meanwhile, in post-Vietnam War America, psychiatrists were recognizing what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. And historians of medicine were recognizing that earlier generations of doctors had viewed much the same symptoms in earlier generations of war veterans, coming up with such diagnoses as soldier’s heart, shell shock, and combat fatigue.

We thus had two concepts that appeared to fit together perfectly:

- Seventeenth-century doctors coining the term “nostalgia” to describe signs of anxiety and depression in Swiss soldiers.

- A pattern of war-related P.T.S.D. cases lurking in the medical literature under other names.

But a look at Johannes Hofer’s dissertation shows that the first of those two concepts is mistaken. There is no link between his original diagnosis of nostalgia and military service. Hofer’s description didn’t go beyond what we now consider homesickness to mention soldiers or other people who had suffered trauma. It may well be that eighteenth-century war veterans suffered from P.T.S.D. and were diagnosed with nostalgia, but that doesn’t mean all or even most cases of nostalgia from that time were triggered by military trauma.

TOMORROW: Three Revolutionary War discussions of nostalgia.

Sunday, June 13, 2021

When and Why Johannes Hofer Wrote about “Nostalgia”

I thought there might well be, but I couldn’t identify any examples, so after the talk I started nosing around to find useful sources. I came across many online articles saying flat out that P.T.S.D. was called “nostalgia” in the Revolutionary period, which would be a good lead—if we could rely on that statement.

For example, Joshua A. Jones wrote in “From Nostalgia to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Mass Society Theory of Psychological Reactions to Combat” (Inquiries, 2013):

Military doctors made the first concerted attempts to categorize and diagnose the manifestations of acute combat reaction for which Johannes Hofer had championed the term “nostalgia” in his 1688 medical dissertation. This classification survived through the end of the Seven Years War and described the disorder as consisting of depression, angst, and exhaustion. Since the symptoms were believed to be associated with soldier’s longing to return home during extended campaigns (not to actual battlefield experiences), both the French and Germans classified the malady as “homesickness”; maladie du pays and heimweh respectively. In Spain, the same symptoms would come to be known as estar roto (“to be broken”). This notion persisted through much of the Napoleonic era (Charvat, 2010).Jones’s citation pointed to Mylea Charvat’s 2010 “History of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Combat," which is a set of PowerPoint slides from a presentation for the Department of Veterans Affairs. One of those slides says, “1678[:] Swiss physician Johannes Hofer coins the term ‘nostalgia.’ to describe symptoms seen in Swiss Troops.” No further citations.

Scholars agree that Johannes Hofer coined the term “nostalgia” as a particular psychological condition that produced physical symptoms. They disagree, as Jones and Charvat did, on when Hofer did so. Some authors say 1678, some ten years later.

Alex Davis’s paper “Coming Home Again: Johannes Hofer, Edmund Spenser, and Premodern Nostalgia” provides an answer to that discrepancy by stating that an edition of Hofer’s Dissertatio Medica de Nostalgia, oder Heimwehe (shown above, beside his portrait from later in life) “is mis-dated on the titlepage to 1678” but was actually published in 1688. Since Hofer was only nine years old in 1678, that makes sense. He published this dissertation and another in the year when he graduated medical school.

So I went looking for Hofer’s Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia to see what he wrote about soldiers’ psyches. Fortunately, the text was translated in 1934 for the Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine.

And I was surprised to find that Hofer wrote nothing about Swiss soldiers or mercenaries. He didn’t coin “nostalgia” as a term for a response to trauma or military experiences. The closest he came was the statement: “[nostalgia] is ascribed to some (authority) for a short time it was frequent with the centurions of the forces in Helvetian Gaul” during Roman times. Hofer’s detailed descriptions of the condition all involved Swiss civilians.

TOMORROW: So how did the diagnosis of “nostalgia” get attached to soldiers?

Saturday, June 12, 2021

Thinking about Feel-Good History

While Blaakman’s remarks were prompted by David McCullough’s book The Pioneers, which is the focus of the latest issue of S.H.E.A.R.’s journal, and by the flimsy “1776 Report” from the last Presidential administration, his concerns can apply to other history projects.

This was snowflake history—history designed to inspire, delight, or comfort, while sheltering its imagined audience from challenging questions about the past. [It] embodied an idea that is not going away anytime soon: that history’s purpose is to make people feel good. . . .Blaakman sees the appeal of history books like McCullough’s lying in “drama,” and he suggests foregrounding the authors’ investigative process to produce that.

For most historians, meanwhile, the primary goal is not to make us feel one way or another, but to help us think: to understand prior worlds, to discover why events unfolded the way they did, and to explain how all of it has shaped the present. . . .

Stories [that center on the origins and character of the nation] carry a lot of baggage. They implicate a primary and deeply political category of their reader’s personal identity, in ways that do not bear as heavily on biographies, microhistories, and global histories, at least not by definition.

Is it inevitable that any nation-centered history will necessarily alienate whole constituencies, even within the nation itself? The optimist in me would like to think it’s not, because it seems more vital than ever for scholars of the early republic to help broad audiences understand themselves and the nation in historical context. As the United States’ semiquincentennial approaches, we will be called on increasingly to do so.

I think those books’ appeal comes from narrative, which includes moments of drama but goes beyond that one ingredient. The historian can indeed be the protagonist of a narrative, but so can the historical actors, even when the author concludes that history is shaped by larger forces and trends beyond individual actions.

Friday, June 11, 2021

The Beard of John Stavely

This fact is sometimes regretted by reenactors who don’t want to shave their modern beards, but the artistic record is clear.

That doesn’t mean there were no bearded men in Revolutionary America. Rather, they were few, and people saw them as unusual. The Boston shoemaker William Scott grew a long beard for religious reasons, and it scared children on the street.

Another man of the period noted for his full beard was John Stavely. We know him as a model for the painter Joseph Wright of Derby. And we know his name only by the inscription on the back of a Wright drawing now in the collection of the Morgan Library:

Portrait ofWe can spot the same bearded face in other Wright paintings and drawings, such as his two versions of The Captive and various studies as the man aged.

John Stavely

who came from Hert-

fordshire with Mr. French

& sat to Mr. Wright in the character of the old man & his ass in the

Sentimental Journey

The Sotheby’s site says:

Wright’s practise of employing old men as models in the 1760s and early ’70s is well documented and the artist’s account book, now preserved in the archives of the National Portrait Gallery in London, includes the details and addresses of several local Derbyshire characters that sat for him on a regular basis. . . . Perhaps his favourite model, however, was a character known as Old John Staveley…Stavely’s most famous role for Wright was as the scientist in The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers. Wright finished this painting in 1771, then went back over it in 1795.

Unfortunately, we don’t appear to have any account of what John Stavely’s family and neighbors thought of his beard. We know only that when Joseph Wright of Derby wanted to paint bearded men, he had a limited pool to choose from.

Thursday, June 10, 2021

The Later Career of Henry DeBerniere

A couple of months later, he drew a map of the Battle of Bunker Hill that I discussed back here.

We have just a few glimpses of DeBerniere through the next few years as the 10th fought at Brooklyn, Germantown, Monmouth, and Rhode Island. He became a lieutenant during the war, a captain-lieutenant sometime in 1783. As of 1792 he was a captain, still with the 10th Regiment, stationed on Jamaica. Three years later, he was promoted to major.

Britain’s wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France opened up more opportunities for career officers. In November 1796, DeBerniere transferred to the 9th Regiment with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Three years later, the regiment fought in Holland, including the Battle of Bergen (shown above).

In 1798 DeBerniere married Elizabeth Longley (1770-1858), eighteen years old and born the year the lieutenant colonel entered the army. That difference in ages may be why later sources estimated he was born later than he was.

Meanwhile, in 1799 Henry’s older brother, retired army officer John Anthony DeBerniere (1744-1812), and his family moved from Ireland to South Carolina. Papers from that branch of the family are in the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society. His gravestone is in the cemetery of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Charleston.

On 10 Nov 1805 three British transport ships sailed from Cork, Ireland, to carry Lt. Col. DeBerniere and the 9th Regiment to a new assignment on the continent. A storm blew up, and one of those ships, the Ariadne, was wrecked off Calais. All the regiment’s staff officers and 262 soldiers became prisoners of war.

The Times of London reported that twenty women and twelve children were also captured. Those might have included Lt. Col. DeBerniere’s wife, their son John (b. 1801), and daughter Elisabeth (b. 1803). If not, Elizabeth DeBerniere later joined her husband in France.

The French government chose not to exchange the regimental commander for an officer held in Britain. DeBerniere remained a prisoner at Nancy, far from the coast in northeastern France, year after year as the wars swirled around him.

Eventually Napoleon had to retreat from Moscow, and the Sixth Coalition formed to pursue his army, defeating it at Liepzig in late 1813 and then entering France. In his Narrative of a Forced Journey Through Spain and France, as a Prisoner of War, in the Years 1810 to 1814, Baron Blayney wrote:

Shortly after the head quarters of the grand army were established at Metz, and the sick and wounded were removed from Mayence, &c. towards Verdun and the interior. For six weeks the roads were crowded with waggons, and all the public buildings at Verdun were converted into hospitals. At the same time an hospital fever prevailed at Mayence, and was conveyed to Metz and Nancy, in which latter place Colonel de Bernière of the 9th regiment fell a victim to it, universally regretted.Henry DeBerniere thus died a captive in the land of his Huguenot ancestors on 6 December 1813.

Parliament approved a £150 annual pension for the widow Elizabeth DeBerniere and her three daughters. The DeBernieres’ only son had already died. Francoise Charlotte Josephine, born while the couple was in France, married the Rev. Newton Smart, and the family took the name of DeBerniere-Smart. Among their descendants is Louis de Bernières, author of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin.

Wednesday, June 09, 2021

The Early Career of Henry DeBerniere

I also promised a look at DeBerniere’s career after the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, which he helped to make happen when and where it did.

My research was complicated and delayed by what David C. Agnew wrote about the DeBerniere family in the genealogical reference book Protestant Exiles from France, Chiefly in the Reign of Louis XIV (1874):

Jean Antoine de Bernière…came over to Ireland. He is reputed by the present French representatives of the family to have been the chief of his name. For conscience sake he left the estate of Bernières near Caen; he is called in the Crommelin Pedigree, “gentilhomme d’aupres d’Alencon.”If that birthyear is correct, then Ens. Henry DeBerniere was only twelve or thirteen years old when he scouted the roads to Worcester and Concord, drew his maps, and wrote his report. That narrative doesn’t read like the writing of a young teenager, and there’s no indication that the people DeBerniere met perceived him as unusually young.

The refugee served under the Earl of Galway at the battle of Almanza; he was wounded and lost a hand; his life was also in danger, but by means of an ancient ring which he wore, and which had been the gift of a French king to one of his ancestors, he was recognised by a tenant on the Bernières lands and received quarter.

On his return to Ireland he married Madeleine Crommelin, only daughter of the great Crommelin. His grandson was Captain [Louis Crommelin] De Bernière of the 30th Regiment, who died from exhaustion after the siege of Senegal in 1762, leaving an only son and heir, Henry Abraham Crommelin de Bernière, who rose to be a Major-General in the British army.

Major-General de Bernière, was born in 1762, and joined the 10th regiment in 1777, at once entering upon active service in America under General [John] Burgoyne.

Furthermore, Agnew was obviously wrong about when Henry DeBerniere joined the British army. He was serving in Boston in early 1775, so he probably enlisted before that. Plus, he wasn’t his father’s “only son.”

This webpage about the Crommelin family offers different and seemingly more reliable information, though it doesn’t cite sources:

In 1739 Louis Bernière married Elinor Donlevy, sister-in-law of the Bishop of Dromore, Louis was also a soldier and saw service in Canada and Senegal where he became ill and was sent home on furlough. He never reached Lisburn, dying at sea in 1762. His wife had died previously in 1759 and their children were taken by relatives to be brought up.Since Henry’s mother died in 1759, he must have been at least sixteen and quite possibly a little older when he did his scouting missions. Not too much older since ensign was the most junior officer’s rank, but at least in his late teens.

The elder son, John Anthony De Bernière born in Lisburn in 1744, was sent to his aunt, the wife of Bishop Marlay, and eventually entered the army. The younger son [Henry] went to Dublin, to the home of Paul Mangin, and in time he also became a soldier, serving in America and France and rising to the rank of Brigadier.

In the 1890s Washington Chauncey Ford published a compilation of “British Officers in America, 1754–1774” in the New England Historical Genealogical Register. It included these listings of commissions:

Birniere, Henry / Ensign / [blank] / 22 August, 1770.Because of the contradictory information, I had to consider the possibility that there were two men named Henry DeBerniere, perhaps cousins, serving in the British army at the same time. But the Army Lists published in the 1770s and 1780s show only one.

Ensign / 10[th Regiment] / 14 September, 1779.

Birniere, John de / Ensign / 55 / 22 November, 1755.

Lieut. / 44 / 9 August, 1760.

Lieut. / 18 / 4 February, 1769.

In the end, I concluded that Henry DeBerniere followed his father and his older brother John into the army in 1770. It looks like the DeBerniere family had connections and a military pedigree but not a lot of money, plus Henry was the younger son. His army career was probably slower than other officers because he couldn’t buy higher ranks as easily.

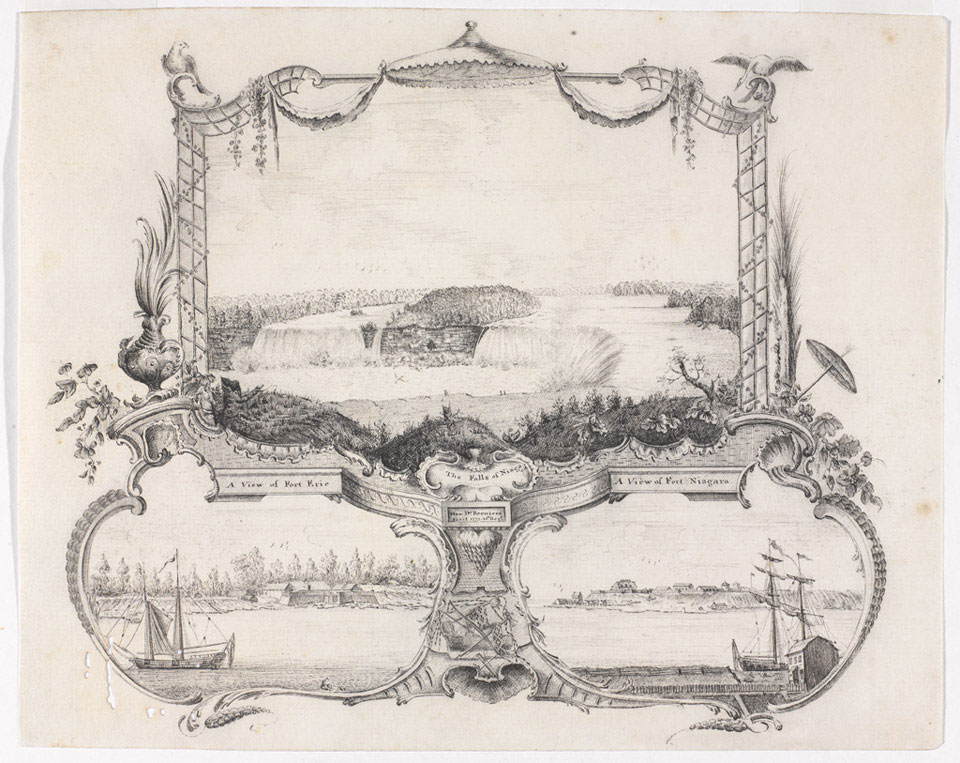

In 1773 the 10th Regiment was stationed along the Niagara River. And we have Ens. DeBerniere’s sketches of Fort Erie, Fort Niagara, and Niagara Falls from that year. Those appear above, courtesy of the U.K.’s National Army Museum. I found another statement saying he probably drew a map of Detroit around the same time.

Thus, by early 1775 Ens. DeBerniere had nearly five years of experience in the army and in North America, and was a practiced draftsman.

TOMORROW: DeBerniere after 1775.