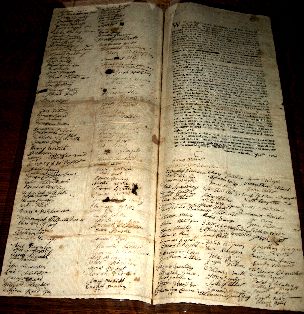

The Boston committee of correspondence sent its draft non-consumption agreement to all towns in Massachusetts and to allies outside of the colony on 8 June. But it didn’t make those documents public within Boston.

Andrews later wrote:

it was not known to be in being in this town (but by the few who promoted it) till near a month after it had been circulated through the country: in which time it went through whole towns with the greatest avidity, every adult of both sexes putting their names to it, saving a very few.By the time Andrews composed that letter, Boston’s Loyalist-leaning newspapers had published the text of the Solemn League and Covenant. But, as I concluded back here, that 23 June publication reflected the Worcester version. The Boston committee would thus have been accurate to say “it originated…from the country.”

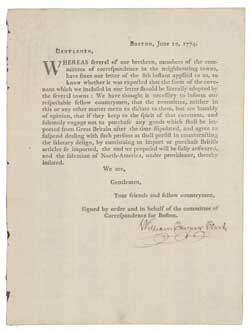

It was sent out in printed copies by the Clerk to the Committee. W[illiam]. Cooper, who accompanied it with a letter intimating that the measure was in general adopted here, whereas upon enquiry I can’t find that a single person in the town has signed it—and the only excuse they now make for so absurd a piece of conduct is, that it originated altogether from the country, without any of their advice or interposition; thinking so palpable a falsehood will remove the just prejudices of the more rational and judicious people among us.

“Altogether” would have been misleading to say since most of the Worcester text echoed Boston’s. But I rather suspect that Andrews inserted that adverb. He tended to exaggerate details, such as that it took “near a month” for the non-consumption agreement to appear in Boston rather than fifteen days.

Still, Andrews was far from alone in his anger at the committee of correspondence. On 17–18 June, as I recounted back here, Boston had a town meeting to hash out the situation. Voters ended up endorsing the committee, but that was before people had read its work.

A week later, everyone in Boston had been able to see the Solemn League and Covenant (Worcester edition) and the letter Cooper had sent. The Loyalists and merchants demanded another session of the ongoing town meeting on the morning of Monday, 27 June.

As described back here, that meeting brought in so many people it moved to Old South.

The complaints led to a motion “that some Censure be now passed By the Town on the Conduct of the Comittee of Correspondence; and that said Committee be annihilated.” Some leading politicians and traders spoke for and against that proposal.

In fact, the discussion went on for so long that the day grew “dark” (in late June!). And still the proponents of the motion said “they had farther to offer.” Cooper as town clerk put on record that those men had been “patiently heard.” The meeting voted to adjourn for the day and pick up their discussion on Tuesday at 10:00 A.M.

TOMORROW: The final vote.