Last week I had my post-midnight visit with Bradley Jay at WBZ-AM radio. The conversation was fun and detailed and as coherent as I can be that late at night.

That segment of the Jay Talking show is now available as a podcast episode titled “Four Loose Cannons.” You can find it for streaming or download at any of these links under the date of 27 July 2017:

One of the topics we discussed was the process of firing an eighteenth-century cannon. Click on the image below for a two-minute demonstration from Fort Niagara.

History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

▼

Monday, July 31, 2017

Sunday, July 30, 2017

Capt. John Trull: “Stand trim, men.”

In 1888 Edward W. Pride’s Tewksbury: A Short History recounted the town’s response to the Lexington Alarm and added:

“Oh, lord, it’s old man Manning again. Quick, let’s cross over—too late, he’s seen us! Yes, good morning, sir! Yes, I remember. You tell me every—uh-huh. Uh-huh. ‘Elbows’! Haha. Yes, that’s a good one, sir. We have to be getting along…”

One of the Tewksbury men was Eliphalet Manning. One of Captain [John] Trull’s grandsons, Mr. Herbert Trull, often related that when a boy, on his way to Salem, he used to pass Manning’s door. Eliphalet would call out: “I fought with your grandfather from Concord to Charlestown. He would cry out to us as we sheltered ourselves behind the trees: ‘Stand trim, men; or the rascals will shoot your elbows off.’”Solid advice for soldiers behind trees, but the habitual past tense means I can’t help but imagine this:

“Oh, lord, it’s old man Manning again. Quick, let’s cross over—too late, he’s seen us! Yes, good morning, sir! Yes, I remember. You tell me every—uh-huh. Uh-huh. ‘Elbows’! Haha. Yes, that’s a good one, sir. We have to be getting along…”

Saturday, July 29, 2017

The Campaign to Repair and Repaint Spell Hall

The Gen. Nathanael Green Homestead in Coventry, Rhode Island, is using Facebook to raise money to fix up the building’s exterior.

The president of the non-profit corporation that maintains the house, Dave Procaccini, says: “we are raising money to be used to repair damaged and rotted clapboards and trim and for a new coat of paint to protect the Greene Homestead, the National Historic Landmark home of George Washington’s Second in Command. Every little bit helps.”

Nathanael Greene, a bachelor forge owner, commissioned that house and moved in in 1770. He referred to the building in letters as “Spell Hall,” perhaps a reference to local children being taught to read there. It remained his residence until 1783, though he was away for significant periods in those years.

Through October, the Greene Homestead is open four days a week.

The president of the non-profit corporation that maintains the house, Dave Procaccini, says: “we are raising money to be used to repair damaged and rotted clapboards and trim and for a new coat of paint to protect the Greene Homestead, the National Historic Landmark home of George Washington’s Second in Command. Every little bit helps.”

Nathanael Greene, a bachelor forge owner, commissioned that house and moved in in 1770. He referred to the building in letters as “Spell Hall,” perhaps a reference to local children being taught to read there. It remained his residence until 1783, though he was away for significant periods in those years.

Through October, the Greene Homestead is open four days a week.

Friday, July 28, 2017

“Concord Secrets” at the Concord Museum, 31 July

On the evening of Monday, 31 July, I’ll speak at the Concord Museum on the topic of “Concord Secrets of 1775.”

Here’s the event description:

This event is part of the museum’s summer series titled “People of Concord,” which “seeks to share the histories of the notable, as well as the less well-known, citizens” of that town. The lecture series continues on the following two Mondays:

Here’s the event description:

In the early spring of 1775, Concord was full of secrets. One prominent farmer was collecting military supplies, including cannon spirited out of Boston and Salem, for Massachusetts’s rebellious Provincial Congress. A neighbor was sending reports on those supplies to the royal governor. Two army officers slipped into town in disguise. And when members of the congress met in Concord, surrounded by their weaponry, one of them was also spying for the governor. On April 18-19, redcoats marched to Concord seeking that arms cache, setting off a war—but both sides continued to keep their secrets.This talk will start at 7:00 P.M. at the Concord Museum. To reserve free seats, use this link or call 978-369-9763 ext. 216.

This event is part of the museum’s summer series titled “People of Concord,” which “seeks to share the histories of the notable, as well as the less well-known, citizens” of that town. The lecture series continues on the following two Mondays:

- 7 August: Concord Museum Curator David Wood talks about William Munroe, master cabinetmaker, who left account books and an 1839 autobiography describing his rise from journeyman to prosperous artisan.

- 14 August: Christie Jackson, Senior Curator at The Trustees of Reservations, explores the Windsor writing-arm chair where Ralph Waldo Emerson sat as he authored Nature while looking out over the pastoral grounds of the Old Manse.

Thursday, July 27, 2017

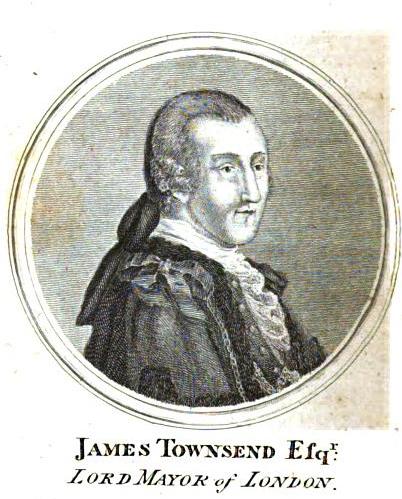

James Townsend, Lord Mayor with a Secret?

James Townsend (1737-1787) was a London alderman from 1769 to his death, sheriff of London in 1769-70 and Lord Mayor in 1772-73.

He was also a Member of Parliament for two stints, in 1767-74 and 1782-87. Unlike his father, who allied with George Grenville, Townsend became part of Lord Shelburne’s wing of the Whigs.

That put him on the left of British politics. The History of Parliament Online says of Townsend:

In 1772 Townsend and John Horne Tooke broke with Wilkes while still remaining radical reformists. That year, Wilkes won more votes for Lord Mayor than anyone else, but the sheriff manipulated the voting process to put Townsend in office instead. That prompted riots against the new mayor, and he served only one term.

In October 2016 Notes and Queries discussed another aspect of Townsend’s life: one of his eight great-grandparents was African. In the part of eastern Africa that Europeans then called the Gold Coast, now Ghana, that woman reportedly had a child with a Dutch soldier.

That child, named Catherine, married James Phipps, a long-time employee of the Royal African Company of England. Toward the end of his life Phipps was the Captain-General of the company and Governor of Cape Coast Castle. In 1722 he lost those posts after being accused of embezzling and abusing power, and the following year he died. Phipps had wanted to bring his wife to Britain, even writing incentives for her to do so into his will, but she never left Africa. Instead, she became a major trader (and slaveowner) on the Gold Coast.

Back around 1715, the couple had sent two of their daughters, Bridget and Susanna, to Britain. Both girls, who had one African grandparent, were then around nine years old. Phipps’s family was surprised to receive “some issue” of him, but they duly sent those girls to a school in Battersea. Phipps’s wealth no doubt helped—there might have been something to those embezzlement charges.

In 1730 Bridget Phipps got married in the Fleet Prison, the venue probably chosen to evade parents and guardians. Her new husband was a London merchant and mining investor named Chauncy Townsend. They had many children, including James.

James Townsend’s legal papers in Britain reportedly contain no hint of his African great-grandmother. Nor does that ancestry appear to have come up in gossip about him as a politician. As Wolfram Latsch wrote in Notes and Queries and this blog post, “this fact was either unknown, or went unnoticed, or it was ignored.” His grandmother’s decision to stay away from Britain was probably a factor in how society perceived the Townsend family.

Latsch nonetheless identifies Townsend as “Britain’s first black MP” and the first black Lord Mayor of London. In one way he indeed was. But if no one knew about his ancestry, in another way he wasn’t.

He was also a Member of Parliament for two stints, in 1767-74 and 1782-87. Unlike his father, who allied with George Grenville, Townsend became part of Lord Shelburne’s wing of the Whigs.

That put him on the left of British politics. The History of Parliament Online says of Townsend:

He made himself conspicuous in Parliament as an advocate of [John] Wilkes’s cause, contributed to his election expenses, and was a foundation member of the Bill of Rights Society. In 1771 he refused to pay the land tax on the ground that Middlesex was not represented in Parliament.That was, of course, an argument about taxation without representation within greater London itself.

In 1772 Townsend and John Horne Tooke broke with Wilkes while still remaining radical reformists. That year, Wilkes won more votes for Lord Mayor than anyone else, but the sheriff manipulated the voting process to put Townsend in office instead. That prompted riots against the new mayor, and he served only one term.

In October 2016 Notes and Queries discussed another aspect of Townsend’s life: one of his eight great-grandparents was African. In the part of eastern Africa that Europeans then called the Gold Coast, now Ghana, that woman reportedly had a child with a Dutch soldier.

That child, named Catherine, married James Phipps, a long-time employee of the Royal African Company of England. Toward the end of his life Phipps was the Captain-General of the company and Governor of Cape Coast Castle. In 1722 he lost those posts after being accused of embezzling and abusing power, and the following year he died. Phipps had wanted to bring his wife to Britain, even writing incentives for her to do so into his will, but she never left Africa. Instead, she became a major trader (and slaveowner) on the Gold Coast.

Back around 1715, the couple had sent two of their daughters, Bridget and Susanna, to Britain. Both girls, who had one African grandparent, were then around nine years old. Phipps’s family was surprised to receive “some issue” of him, but they duly sent those girls to a school in Battersea. Phipps’s wealth no doubt helped—there might have been something to those embezzlement charges.

In 1730 Bridget Phipps got married in the Fleet Prison, the venue probably chosen to evade parents and guardians. Her new husband was a London merchant and mining investor named Chauncy Townsend. They had many children, including James.

James Townsend’s legal papers in Britain reportedly contain no hint of his African great-grandmother. Nor does that ancestry appear to have come up in gossip about him as a politician. As Wolfram Latsch wrote in Notes and Queries and this blog post, “this fact was either unknown, or went unnoticed, or it was ignored.” His grandmother’s decision to stay away from Britain was probably a factor in how society perceived the Townsend family.

Latsch nonetheless identifies Townsend as “Britain’s first black MP” and the first black Lord Mayor of London. In one way he indeed was. But if no one knew about his ancestry, in another way he wasn’t.

Wednesday, July 26, 2017

“With great zeal I went to Genl Washington”

Elias Boudinot (1740-1821) was a Continental Congress delegate from New Jersey, eventually president of that body, and later a U.S. Congressman and director of the U.S. Mint. He was brother-in-law of Richard Stockton twice over (i.e., each married the other’s sister).

For a considerable period of the war Boudinot was the American commissary of prisoners, meaning he was responsible for feeding and supplying captured British and Hessian soldiers. As such, he often worked closely with the Congress, local authorities, and Gen. George Washington.

Boudinot left behind a manuscript in which he explained:

Here’s one example:

I’ve been reviewing the final season of Turn for Den of Geek; you can find my assessments here. Gen. Washington, played by Ian Kahn, remains one of the decidedly best parts of the show.

For a considerable period of the war Boudinot was the American commissary of prisoners, meaning he was responsible for feeding and supplying captured British and Hessian soldiers. As such, he often worked closely with the Congress, local authorities, and Gen. George Washington.

Boudinot left behind a manuscript in which he explained:

A great many interesting anecdotes, that happened during the American Revolutionary War, are likely to be lost to Posterity, by the negligence of the parties concerned, in not recording them, so that in future time they may be resorted to, as throwing great light on the eventful Crisis, of this important Æra—I shall therefore without any attention to order, but merely as they arise in my memory, set down those I have had any acquaintance with, attending principally to the TRUTH of the facts.That manuscript was published in 1890 as Boudinot’s Journal or Historical Recollections of American Events during the Revolutionary War. It’s not really a journal since he didn’t record events as they happened; indeed, most of the stories aren’t tied to specific dates. But they’re valuable nonetheless.

Here’s one example:

In [April] 1777 Genl [Benjamin] Lincoln, was surprised at the Dawn of Day in his Quarters at Bound Brook. by Lord Cornwallis. who had marched from Brunswick passed his out Centinels captured or destroyed his main guard, and was at the Genls Quarters before he knew anything of it. He had but just time to escape out of a back door. Several men were killed and one or two pieces of ordnance taken.When I read that story, I thought that the interaction with Washington could have come right out of the television show Turn: Washington’s Spies, given how it presents the commander’s character.

It was sometime a mystery how this had been effected with so much secrecy, till I was well informed by a Gentn of note who was with the Enemy at Brunswick, that a certain Farmer whose name he mentioned and who lived in the midst of our Camp had communicated to Lord Cornwallis our Countersign, by which he had accomplished his intentions,

My spirit was very much aroused ags this Traitor and with great zeal I went to Genl Washington with the information, stating the substance of it. but keeping back the name of my informant; as he had assured me his life depended on my prudence & faithfulness to him; I urged the Genl, (to give) orders to sieze the Culprit without delay & make an Example of him. The Genl did not immediately answer me. on which I repeated my request.

He then said. did not you tell me that the life of your informant depended on your secrecy,—would you take up a Citizen & confine him without letting him know his crime or his accuser.—No—let him alone for the present: watch him carefully. and if you can catch him in any other crime. so as to confront him by witnesses. we will then punish him severely.——

My mortification was very great. to think. that I who had entered the Army to watch the Military & preserve the civil rights of my fellow citizens. should be so reproved by a Military man, who was so interested in having acted otherwise I recd it as a severe lecture on my own imprudence

I’ve been reviewing the final season of Turn for Den of Geek; you can find my assessments here. Gen. Washington, played by Ian Kahn, remains one of the decidedly best parts of the show.

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

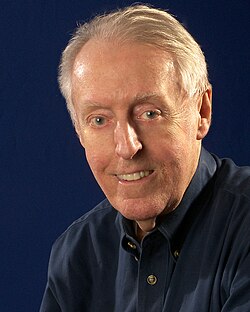

Thomas Fleming: Four Pages a Day

The author Thomas Fleming died this week at the age of ninety.

As I described back here, in 1960 Tom was a journalist putting out his first book. Now We Are Enemies was the first full-length narrative of the Battle of Bunker Hill published since the nineteenth century. It launched his career as a historical writer.

Inspired by advice he received early on to write four pages a day, six days a week, Tom completed more than fifty books in all. The best-selling title was probably Liberty!: The American Revolution, based on the P.B.S. television series. But his own studies of the Revolutionary War covered everything from a single battle in New Jersey (The Forgotten Victory) to Yorktown (Beat the Last Drum) and beyond (The Perils of Peace).

Tom also wrote on other periods of American history, he wrote historical fiction, and he wrote books for younger readers. In 2010 I got to attend a staged reading of a play he had composed decades earlier about Dr. Joseph Warren and Dr. Benjamin Church.

I had the pleasure of meeting and corresponding with Tom a few times. What struck me most was his enthusiasm for researching history and communicating it. To illustrate that, in 2009 I analyzed how he’d come to misattribute a few words about Dr. Warren to Abigail Adams. The next time we talked, Tom brought up that post, congratulated me on spotting what had happened, and even seemed happy to see an explanation. A small slip fifty years earlier meant much less to him than the pleasure of learning more.

As I described back here, in 1960 Tom was a journalist putting out his first book. Now We Are Enemies was the first full-length narrative of the Battle of Bunker Hill published since the nineteenth century. It launched his career as a historical writer.

Inspired by advice he received early on to write four pages a day, six days a week, Tom completed more than fifty books in all. The best-selling title was probably Liberty!: The American Revolution, based on the P.B.S. television series. But his own studies of the Revolutionary War covered everything from a single battle in New Jersey (The Forgotten Victory) to Yorktown (Beat the Last Drum) and beyond (The Perils of Peace).

Tom also wrote on other periods of American history, he wrote historical fiction, and he wrote books for younger readers. In 2010 I got to attend a staged reading of a play he had composed decades earlier about Dr. Joseph Warren and Dr. Benjamin Church.

I had the pleasure of meeting and corresponding with Tom a few times. What struck me most was his enthusiasm for researching history and communicating it. To illustrate that, in 2009 I analyzed how he’d come to misattribute a few words about Dr. Warren to Abigail Adams. The next time we talked, Tom brought up that post, congratulated me on spotting what had happened, and even seemed happy to see an explanation. A small slip fifty years earlier meant much less to him than the pleasure of learning more.

Monday, July 24, 2017

Hannah Snell’s Wound

Last month I quoted a news item from 1771 about Hannah Snell, celebrated in the British Empire for having served as a marine in the late 1740s.

During Britain’s early campaigns in India, Snell was wounded in the legs and groin. Nevertheless, her superiors didn’t discover that she was a woman. That provoked some questions, so I looked up the portion of the book about Snell that described her wounding.

This is from an 1801 edition of The Female Warrior:

At least one later author assumed that the “black woman” in Snell’s eighteenth-century biography was a native of India rather than, say, an African attached to the army. Either way, it’s an interesting example of women working together.

During Britain’s early campaigns in India, Snell was wounded in the legs and groin. Nevertheless, her superiors didn’t discover that she was a woman. That provoked some questions, so I looked up the portion of the book about Snell that described her wounding.

This is from an 1801 edition of The Female Warrior:

During all this time, our heroine still maintained her wonted intrepidity, and behaved in every respect consistent with the character of a brave British soldier. She fired during the engagement, no less than thirty-seven rounds, and received six shots in her right leg, and live in the left; and what was still more painful, a dangerous one in the groin.Curious as it seems, the Royal Navy did have a ship named the Tartar Pink. In 1739 it brought news of Britain’s rising hostilities with Spain to Boston. That was the start of the War of the Austrian Succession, which was still going on when Snell joined the military in 1747.

Distressed in her mind, lest the surgeons should discover the wound in her groin, and consequently her sex, which she was determined to conceal, even at the hazard of her life.—Confirmed in this resolution, she communicated her design to a black woman, who attended her, and who had access to the surgeon’s medicines, and begged her assistance. Her pain, now became very acute; and with the generosity of the black woman, who brought her lint, salve, &c. she endeavoured to extract the ball; by probing the wound with her finger, till she could feel the ball, after which she thrust in her finger and thumb, and pulled it out. This was a painful and dangerous operation; but she was resolved to brave every difficulty, rather than expose her sex, and in a little time she made a perfect cure.

As the heavy rains, and the violent claps of thunder were now set in, (being what they term in that country, the monsoons) the siege was entirely raised.

Our heroine being so dangerously wounded, was sent to an hospital, at Cuddylorum; and was attended by Mr. Belchier and Mr. Hancock, two able surgeons; from whom she concealed the wound in her groin.

During her residence in the hospital, the greater part of the fleet sailed; but as soon as she was perfectly cured, was sent on board the Tartar Pink, which then lay in the harbour, and continued to do the duty of a sailor, till the return of the fleet from Madras.

At least one later author assumed that the “black woman” in Snell’s eighteenth-century biography was a native of India rather than, say, an African attached to the army. Either way, it’s an interesting example of women working together.

Sunday, July 23, 2017

Talking About Revolutionary Massachusetts This Week

From midnight to 1:00 A.M. on Wednesday, 26 July, I’m scheduled to be interviewed by Bradley Jay on his radio show, Jay Talking. That will be on WBZ, 1030 AM.

[CORRECTION: It turns out that when I agreed to be on the show on 26 July, the producer was thinking that’s the date when I’d show up at the studio for a show to be broadcast on 27 July. So the conversation will actually happen early on Thursday.]

(Assuming, that is, that the U.S. Constitution is still operative and we haven’t stumbled into any wars that will preempt regular programming. Hard to be confident these days.)

I understand that Jay is a fan of Revolutionary history. I expect we’ll talk about The Road to Concord, Gen. Washington in Cambridge, and other gossip I’ve collected over the years. But this will be a new experience.

On Saturday, 29 July, I’ll be one of the many speakers at History Camp Pioneer Valley, to be held at the Kittredge Center at Holyoke Community College. This is the second annual gathering of history enthusiasts sharing their research to be organized by the Pioneer Valley History Network.

My presentation will be “An Assassin in Pre-Revolutionary Boston: The Strange Case of Samuel Dyer.” Other presentations on Revolutionary history include “Resurrecting the Memory of Major Joseph Hawley of Northampton: John Adams’s Campaign for a Forgotten Patriot” by Morgan E. Kolakowski, “A Forgotten ‘Hessian’ Prisoner in Brimfield during the Revolutionary War” by Larry and Kitty Lowenthal, “Early Black American Patriotism” by Adam McNeil, and “Pioneer Valley Gravestones (and some of the men who made them), c. 1650-1850” by Bob Drinkwater.

As of today there are still a few slots available for History Camp Pioneer Valley.

[CORRECTION: It turns out that when I agreed to be on the show on 26 July, the producer was thinking that’s the date when I’d show up at the studio for a show to be broadcast on 27 July. So the conversation will actually happen early on Thursday.]

(Assuming, that is, that the U.S. Constitution is still operative and we haven’t stumbled into any wars that will preempt regular programming. Hard to be confident these days.)

I understand that Jay is a fan of Revolutionary history. I expect we’ll talk about The Road to Concord, Gen. Washington in Cambridge, and other gossip I’ve collected over the years. But this will be a new experience.

On Saturday, 29 July, I’ll be one of the many speakers at History Camp Pioneer Valley, to be held at the Kittredge Center at Holyoke Community College. This is the second annual gathering of history enthusiasts sharing their research to be organized by the Pioneer Valley History Network.

My presentation will be “An Assassin in Pre-Revolutionary Boston: The Strange Case of Samuel Dyer.” Other presentations on Revolutionary history include “Resurrecting the Memory of Major Joseph Hawley of Northampton: John Adams’s Campaign for a Forgotten Patriot” by Morgan E. Kolakowski, “A Forgotten ‘Hessian’ Prisoner in Brimfield during the Revolutionary War” by Larry and Kitty Lowenthal, “Early Black American Patriotism” by Adam McNeil, and “Pioneer Valley Gravestones (and some of the men who made them), c. 1650-1850” by Bob Drinkwater.

As of today there are still a few slots available for History Camp Pioneer Valley.

Saturday, July 22, 2017

“Last Argument” Symposium at Fort Ti, 5-6 Aug.

Fort Ticonderoga will host a symposium on 5-6 August titled “New Perspectives on the Last Argument of Kings: A Ticonderoga Seminar on 18th-Century Artillery.”

This event complements the exhibit “The Last Argument of Kings: The Art and Science of 18th-Century Artillery,” which runs at the site through October 29.

Presenters from Fort Ticonderoga’s own staff and elsewhere include:

I’m already signed up.

This event complements the exhibit “The Last Argument of Kings: The Art and Science of 18th-Century Artillery,” which runs at the site through October 29.

Presenters from Fort Ticonderoga’s own staff and elsewhere include:

- Stuart Lilie, “Artillery at This Post: Three Case Studies of Artillery at Ticonderoga.”

- Matthew Keagle, “Lost in Boston: The Artillery of Carillon/Ticonderoga” and “Pell’s Citadel: The Ticonderoga Artillery Collection.”

- Nicholas Spadone, “Green Wood and Wet Paint: American Traveling Carriages at Ticonderoga.”

- Christopher Bryant, “Ultima Ratio Regum: A Pair of Vallere 4-Pounders at Yorktown and Beyond.”

- Richard Colton, “The American Foundry-Springfield Arsenal, Massachusetts, 1782-1800: Assuring Independence.”

- Andrew De Lisle, “If you are satisfied with the methods the workers have found…then so am I: Reproduction as a method of understanding Eighteenth-century Artillery.”

- Eric Schnitzer, “Pack Horses, Grasshoppers, and Butterflies reconsidered: British light 3-pounders of the 1770s.”

- Robert A. Selig, “The Politics of Arming America or: Why are there still more than 50 Vallere 4-pound cannon in the United States but only 3 in all of Europe?”

- Christopher Waters, “When the King’s Last Argument is but a whimper: Artillery Deployment in Antigua’s Colonial Fortifications.”

I’m already signed up.

Friday, July 21, 2017

Colonial Newspaper Subscription Prices

Last month I posted twice about the cost of advertising in colonial American newspapers.

One source of those articles, the 1884 U.S. Census Office report “The Newspaper and Periodical Press” by S. N. D. North, also discussed what pre-Revolutionary newspapers charged their readers for subscriptions:

One source of those articles, the 1884 U.S. Census Office report “The Newspaper and Periodical Press” by S. N. D. North, also discussed what pre-Revolutionary newspapers charged their readers for subscriptions:

The colonial newspapers were sold at prices which varied according to the location and the currency of that location. The latter fluctuated so frequently in value that it is not always possible at this date to determine precisely the sum that the publisher regarded himself entitled to receive from his patrons; but there is sufficient reason to believe that this sum was a nearly uniform one in the respective colonies, and that it did not vary greatly in any one colony from the standard established in all the others.Supplementing North’s rundown, here are the subscription prices I found this spring:

John Campbell, when he founded the News-Letter in 1704, may be said to have established for his own and for subsequent generations the prevailing price of the weekly newspaper. He received the equivalent of $2 of our present currency, but did not think it worth while to advertise his price of subscription in the paper itself. This was a neglect to take advantage of an opportunity which found several imitators in the subsequent colonial newspapers. The Boston Gazette and Weekly Journal (1719) was sold for 16s. a year, and 20s. when sealed, payable quarterly, and at the value of currency at that time this was equivalent to $250 in our present money.

The American Magazine, a monthly periodical of 50 pages, founded in 1743, was sold for 3s., new tenor, a quarter, being at the rate of 50 cents, or $2 per annum. The Rehearsal, founded in 1731, was sold originally for 20s., but was reduced from that price to 16s. when [Thomas] Fleet took possession of it in 1733.

The Boston Advertiser was sold for 5s.4d. “lawful money”, and the Boston Chronicle (1767) for 6s.8d.—“but a very small consideration for a newspaper on a large sheet and well printed,” according to [Isaiah] Thomas, but likely to be regarded as a high price for a similar newspaper in these days.

The Christian History, weekly, 1743, was sold for 2s., new tenor, per quarter, but subsequently 6d. more was added to its price, “covered, sealed, and directed.” The American Magazine and Historical Chronicle, a monthly of 50 pages, sold for 3s., new tenor, per quarter, the equivalent of $150 per year.

Nevertheless, 6s.8d. appears to have been the ruling price at this period, for the Salem Essex Gazette (1768) and the Norwich Packet (1773) were vended at that rate. The New Hampshire Gazette (1756) was sold for “one dollar per annum, or its equivalent in bills of credit, computing a dollar this year at four pounds, old tenor”. The Portsmouth Mercury (1765) was sold for “one dollar, or six pounds o.t. per year; one-half to be paid at entrance”.

Thomas Fleet, who discontinued the Weekly Rehearsal in 1735 and began the publication of the Boston Evening Post on a half sheet of large foolscap paper, regarded the prevailing price for newspapers altogether too low, and in a dunning advertisement to his subscribers he declared:

In the days of Mr. Campbell, who published a newspaper here, which is forty years ago, Paper was bought for eight or nine shillings a Ream, and now tis Five Pounds; his Paper was never more than half a sheet, and that he had Two Dollars a year for, and had also the art of getting his Pay for it; and that size has continued until within a little more than one year, since which we are expected to publish a whole Sheet, so that the Paper now stands us in near as much as all the other charges.In Pennsylvania the prices of newspapers were more uniform than in New England. The Philadelphia American Weekly Mercury, the first paper founded in that city, and the first outside of New England, being the third in the colonies, was sold for 10s. per annum. The Philadelphia Gazette (1733) was sold for the same price, as was also the Philadelphia Journal (1766), the Chronicle (1767), and the Ledger (1775). The Philadelphia Evening Post, founded in 1775, and issued three times a week, was sold at a price of two pennies for each paper, or 3s. the quarter. The Dutch [actually German] and English Gazette was sold for 10s. in 1749, when it was a weekly publication, and for 5s. in 1751, when it became a fortnightly publication.

The New York Weekly Journal (1733) was sold for 3s. the quarter. The Virginia Gazette (1766) was 12s.6d. per year [Purdie and Dixon offered that price in 1770, William Rind the same in 1771]. There was a notable increase in prices during the war in several cases, and the New Jersey Gazette, which was founded in 1777, fixed its price at 26s. per annum.

- New-England Courant under (nominally) Benjamin Franklin, 1723, 12s. per year or 4d. each issue.

- New-York Mercury under Hugh Gaine, 1756, 12s. per year, rising to 14s. in 1757 to defray the cost of a provincial stamp tax, plus another 7s.6d. for delivery to Connecticut.

- Massachusetts Spy under Zechariah Fowle and Isaiah Thomas, 1770, 5s.

- Massachusetts Spy under Thomas alone, 1774, 6s.8d. unsealed, 8s. “sealed and directed.” Thomas continued to charge that price after moving to Worcester in 1775.

- Pennsylvania Packet under John Dunlap, 1771, 10s.

- North-Carolina Gazette under James Davis, 1775, 16s.

- New-York Packet under Samuel Loudon, 1776, 12s.

Thursday, July 20, 2017

An Aged Veteran and “The Young Provincial”

I’ve been discussing the Rev. W. B. O. Peabody’s sketch “The Young Provincial,” published in 1829, and Jacob Frost’s 1832 claim for a pension as a Revolutionary War veteran. Together they raise interesting questions.

First, looking just at the pension file, Jacob Frost’s wound on Breed’s Hill was bad enough to disable him but not to kill him, even with months in prisons and eighteenth-century medicine and hygiene. He must have had one hell of an immune system.

That wound also wasn’t bad enough to keep Frost from reenlisting for a short stint in 1780. Probably his experience as a soldier in battle and a prisoner of war was a reason the company made him its orderly sergeant. Yet that same wound was enough to earn Frost an invalid pension after the war. I suspect it was awarded in recognition of his suffering as a prisoner as much as for actual disability.

Next the bigger question of how Frost’s experiences relate to “The Young Provincial.” Dave Marcus of the Tewksbury Historical Society spotted the strong parallels between “The Young Provincial” and Jacob Frost’s experiences, as this article from the Tewksbury Town Crier in 2014 reported.

The Springfield Republican article from 1829 confirms that connection: “all the narrative parts of it are facts, in the life of a Mr. FROST, now living in Norway, Maine.” Even more clearly it made a connection between that literary sketch and “Dr. JOSHUA FROST of this town,” the veteran’s little brother.

Tewksbury vital records confirm that Jacob Frost, born 9 July 1753, had a little brother named Joshua, born 2 Dec 1765 and thus nine years old at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, just as the newspaper stated. Dr. Joshua Frost graduated from Harvard in 1793.

(Curiously, Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield from 1893 says that Dr. Frost was “born in Fryeburg, Me., in 1767.” Fryeburg wasn’t even formed into a town until 1777. It’s about thirty miles from Norway, where Jacob settled, but perhaps the two communities were more closely linked in the eighteenth century. But there’s some mix-up there.)

Given the Springfield newspaper’s hints, it seems likely that the Rev. W. B. O. Peabody heard stories about Jacob Frost from the old soldier himself during a visit, or from Dr. Frost, talking about his big brother.

The next question is whether “The Young Provincial” is a reliable source on Jacob Frost’s military experiences, filling out the bare-bones account that he submitted to the federal government. And on that question I’m skeptical. I think Peabody took so much literary license that we can’t accept any particular detail as reflecting Frost’s own story unless it also appears in his own account.

It’s not just a matter of how much dramatic detail “The Young Provincial” has but also how details contradict Frost’s own statement:

(Thanks once again to Boston National Historical Park’s Jocelyn Gould for setting me off on this investigation. The photo above is the headquarters of Norway, Maine’s historical society; Jacob Frost would have known that 1828 building in its original location.)

First, looking just at the pension file, Jacob Frost’s wound on Breed’s Hill was bad enough to disable him but not to kill him, even with months in prisons and eighteenth-century medicine and hygiene. He must have had one hell of an immune system.

That wound also wasn’t bad enough to keep Frost from reenlisting for a short stint in 1780. Probably his experience as a soldier in battle and a prisoner of war was a reason the company made him its orderly sergeant. Yet that same wound was enough to earn Frost an invalid pension after the war. I suspect it was awarded in recognition of his suffering as a prisoner as much as for actual disability.

Next the bigger question of how Frost’s experiences relate to “The Young Provincial.” Dave Marcus of the Tewksbury Historical Society spotted the strong parallels between “The Young Provincial” and Jacob Frost’s experiences, as this article from the Tewksbury Town Crier in 2014 reported.

The Springfield Republican article from 1829 confirms that connection: “all the narrative parts of it are facts, in the life of a Mr. FROST, now living in Norway, Maine.” Even more clearly it made a connection between that literary sketch and “Dr. JOSHUA FROST of this town,” the veteran’s little brother.

Tewksbury vital records confirm that Jacob Frost, born 9 July 1753, had a little brother named Joshua, born 2 Dec 1765 and thus nine years old at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, just as the newspaper stated. Dr. Joshua Frost graduated from Harvard in 1793.

(Curiously, Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield from 1893 says that Dr. Frost was “born in Fryeburg, Me., in 1767.” Fryeburg wasn’t even formed into a town until 1777. It’s about thirty miles from Norway, where Jacob settled, but perhaps the two communities were more closely linked in the eighteenth century. But there’s some mix-up there.)

Given the Springfield newspaper’s hints, it seems likely that the Rev. W. B. O. Peabody heard stories about Jacob Frost from the old soldier himself during a visit, or from Dr. Frost, talking about his big brother.

The next question is whether “The Young Provincial” is a reliable source on Jacob Frost’s military experiences, filling out the bare-bones account that he submitted to the federal government. And on that question I’m skeptical. I think Peabody took so much literary license that we can’t accept any particular detail as reflecting Frost’s own story unless it also appears in his own account.

It’s not just a matter of how much dramatic detail “The Young Provincial” has but also how details contradict Frost’s own statement:

- Frost stated that after the Battle of Lexington and Concord “he immediately enlisted at Cambridge near Boston for a term of eight months.” The narrator of “The Young Provincial” says he went home after the battle, joined a company in Tewksbury, and “arrived at the camp the evening before the battle of Bunker Hill.”

- Frost was quite clear that he “was employed on the night previous to the battle of Bunker Hill on the 17th. Day of June 1775, in throwing up breast works.” The “Young Provincial” narrator describes other men doing that work; he “happened to reach the spot just as the morning was breaking in the sky.” (Veterans who worked all night digging and then had to fight the battle tended not to let anyone forget.)

- Frost was “severely wounded in the hip” during that battle. For the narrator, “the ball entered my side,” and he also “was beaten with muskets on the head.”

- The “Young Provincial” arrives home “on a clear summer afternoon.” Frost stated it was “the last of September.”

- The final scene of “The Young Provincial” turns on the soldier’s family believing him to be dead, based on a report from a companion on the battlefield. In 1775 and 1776, Massachusetts newspapers published lists of provincial prisoners from the Battle of Bunker Hill which told everyone that Frost was still alive. His return home was a surprise, but not that much of a surprise.

(Thanks once again to Boston National Historical Park’s Jocelyn Gould for setting me off on this investigation. The photo above is the headquarters of Norway, Maine’s historical society; Jacob Frost would have known that 1828 building in its original location.)

Wednesday, July 19, 2017

The True Author of “The Young Provincial”

The idea that Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote “The Young Provincial,” the sketch I quoted yesterday from The Token, for 1830, wasn’t a bad guess.

In 1830 Hawthorne wrote to the editor of that volume, Samuel G. Goodrich, proposing a collection titled Provincial Tales. The next year’s volume of The Token contained two sketches unquestionably by Hawthorne, and he wrote more for later volumes—so many that in one year Goodrich worried about publishing too many pieces by one author.

Hawthorne never claimed “The Young Provincial,” but he left some hints about not wanting some of his early literary output rediscovered. And he suppressed his 1828 novel Fanshawe altogether.

In 1890 Moncure D. Conway published a biography of Hawthorne stating positively that “The Young Provincial” was one of his early stories that had “escaped the attention” of scholars. He repeated that claim in an 8 June 1901 article in the New York Times Saturday Review.

Franklin B. Sanborn also argued that Hawthorne wrote seven previously unrecognized stories, including “The Young Provincial,” in the New England Magazine in 1898 and elsewhere. George Edward Woodbury discussed the sketch as likely Hawthorne in his 1902 biography of the author, and John Erskine accepted that possibility in Leading American Novelists (1910).

There were some doubters. Nina E. Browne said the sketch “probably was not written by Hawthorne” in her 1905 bibliography of his work. But there was enough consensus about “The Young Provincial” that variously titled editions of Hawthorne’s collected works published in 1900 included it in an appendix.

However, back in late 1829, when The Token, for 1830 first appeared for sale, the author of “The Young Provincial” was named. The 25 November Springfield Republican reprinted the story and reported:

The Rev. William Bourn Oliver Peabody (1799-1847, shown above) was a Unitarian minister in Springfield. He wrote poems, hymns, book reviews, and short biographies for Jared Sparks’s Library of American Biography as well as sermons. The Token, for 1828 contained his poem “To an Aged Elm,” so he was definitely in touch with Goodrich.

After Peabody died in 1847, his twin brother Oliver William Bourn Peabody started to write a biography to be published with his literary work. “A few of his productions may be found in ‘The Token’,” Oliver wrote about his brother William. Oliver also dabbled in literary pursuits, publishing a poem in The Token, for 1831 himself, while working as a Boston lawyer, legislator, bureaucrat, and college professor. But in 1845 the pull of parallelism had become too strong, and Oliver became a Unitarian minister like his twin, preaching in Vermont.

In fact, that parallelism was so strong that Oliver died in 1848, just one year after his brother. The biography of William had to be completed by a friend before being published in a collection of William’s sermons. In 1850, Everett Peabody edited The Literary Remains of the Late William B. O. Peabody, D.D. He chose only reviews and poetry from the North American Review, leaving out “The Young Provincial” and everything like it.

As a result, no book credited W. B. O. Peabody with that sketch until Volume XI of the Centenary Edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne. That scholarly edition of Hawthorne’s tales cited the newspaper articles I quoted above about “The Young Provincial.” It also took four other tales that Conway and Sanborn had attributed to Hawthorne and showed they had been written by Lydia Maria Child, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Edward Everett.

Ironically, the 1900 collections of Hawthorne that include “The Young Provincial” are now in the public domain and thus available on Google Book and as digital texts. The more reliable Centenary Edition is protected by copyright and priced for research libraries. Therefore, people looking into “The Young Provincial” are once again apt to come across statements that it was most likely written by Hawthorne—I did so at first. This book dealer is even selling The Token, for 1830 on the possibility that it might contain an early Hawthorne story.

But all that literary investigation is just in service of the question of whether “The Young Provincial” has historical value. Is it a reliable narration of a certain private’s experiences in the first year and a half of the Revolutionary War?

TOMORROW: Back to Jacob Frost.

In 1830 Hawthorne wrote to the editor of that volume, Samuel G. Goodrich, proposing a collection titled Provincial Tales. The next year’s volume of The Token contained two sketches unquestionably by Hawthorne, and he wrote more for later volumes—so many that in one year Goodrich worried about publishing too many pieces by one author.

Hawthorne never claimed “The Young Provincial,” but he left some hints about not wanting some of his early literary output rediscovered. And he suppressed his 1828 novel Fanshawe altogether.

In 1890 Moncure D. Conway published a biography of Hawthorne stating positively that “The Young Provincial” was one of his early stories that had “escaped the attention” of scholars. He repeated that claim in an 8 June 1901 article in the New York Times Saturday Review.

Franklin B. Sanborn also argued that Hawthorne wrote seven previously unrecognized stories, including “The Young Provincial,” in the New England Magazine in 1898 and elsewhere. George Edward Woodbury discussed the sketch as likely Hawthorne in his 1902 biography of the author, and John Erskine accepted that possibility in Leading American Novelists (1910).

There were some doubters. Nina E. Browne said the sketch “probably was not written by Hawthorne” in her 1905 bibliography of his work. But there was enough consensus about “The Young Provincial” that variously titled editions of Hawthorne’s collected works published in 1900 included it in an appendix.

However, back in late 1829, when The Token, for 1830 first appeared for sale, the author of “The Young Provincial” was named. The 25 November Springfield Republican reprinted the story and reported:

The Token, for 1830.—This elegant little work, published S. G. Goodrich, Boston, has been before the public some weeks. We have had opportunity to read only the following story; but if this may be considered a specimen of the merits of the other articles, the book must be interesting. Its typographical execution exceeds any thing of the kind we ever saw. It will doubtless be gratifying to our readers in this vicinity, to know that the following story was written by a gentlemen of this town who has contributed much to elevate the standard of American literature; and that all the narrative parts of it are facts, in the life of a Mr. FROST, now living in Norway, Maine, and brother of Dr. JOSHUA FROST of this town. Dr. Frost, who was then about nine years of age, was “the little brother who ran to the meeting-house” to carry the tidings of the young provincial’s return from captivity.That item was reprinted in the Essex Register, and then in the 13 Feb 1830 Columbian Centinel. Those newspapers added a phrase to the Republican’s identification of the author as a Springfield local: “[meaning, we presume, the Rev. W. B. O. Peabody.]” The Essex Register was published in Salem, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s home town, but he didn’t object to crediting the Rev. W. B. O. Peabody with “The Young Provincial.”

The Rev. William Bourn Oliver Peabody (1799-1847, shown above) was a Unitarian minister in Springfield. He wrote poems, hymns, book reviews, and short biographies for Jared Sparks’s Library of American Biography as well as sermons. The Token, for 1828 contained his poem “To an Aged Elm,” so he was definitely in touch with Goodrich.

After Peabody died in 1847, his twin brother Oliver William Bourn Peabody started to write a biography to be published with his literary work. “A few of his productions may be found in ‘The Token’,” Oliver wrote about his brother William. Oliver also dabbled in literary pursuits, publishing a poem in The Token, for 1831 himself, while working as a Boston lawyer, legislator, bureaucrat, and college professor. But in 1845 the pull of parallelism had become too strong, and Oliver became a Unitarian minister like his twin, preaching in Vermont.

In fact, that parallelism was so strong that Oliver died in 1848, just one year after his brother. The biography of William had to be completed by a friend before being published in a collection of William’s sermons. In 1850, Everett Peabody edited The Literary Remains of the Late William B. O. Peabody, D.D. He chose only reviews and poetry from the North American Review, leaving out “The Young Provincial” and everything like it.

As a result, no book credited W. B. O. Peabody with that sketch until Volume XI of the Centenary Edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne. That scholarly edition of Hawthorne’s tales cited the newspaper articles I quoted above about “The Young Provincial.” It also took four other tales that Conway and Sanborn had attributed to Hawthorne and showed they had been written by Lydia Maria Child, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Edward Everett.

Ironically, the 1900 collections of Hawthorne that include “The Young Provincial” are now in the public domain and thus available on Google Book and as digital texts. The more reliable Centenary Edition is protected by copyright and priced for research libraries. Therefore, people looking into “The Young Provincial” are once again apt to come across statements that it was most likely written by Hawthorne—I did so at first. This book dealer is even selling The Token, for 1830 on the possibility that it might contain an early Hawthorne story.

But all that literary investigation is just in service of the question of whether “The Young Provincial” has historical value. Is it a reliable narration of a certain private’s experiences in the first year and a half of the Revolutionary War?

TOMORROW: Back to Jacob Frost.

Tuesday, July 18, 2017

“The Young Provincial” on Bunker Hill

At the end of 1829 the writer and editor Samuel G. Goodrich published an anthology of short stories and literary sketches by various authors titled The Token, for 1830.

One of those pieces was titled “The Young Provincial,” and it began:

The story the old man tells those boys begins with him as a youth in “Tewksbury, a small town in Middlesex county.” He and the other “younger men of our village” formed a minuteman company. The story says: “Perhaps if you accent the last syllable of that word minute, it would better describe a considerable portion of our number, of whom I was one.”

The narrator of the “Young Provincial” describes experiences that closely parallel those of Jacob Frost, quoted yesterday, except in a much more elevated language. This is how Frost’s pension application of 1832 discussed the Battle of Bunker Hill:

“The Young Provincial” thus seems to be an elevated version of Jacob Frost’s experiences. But did the author really hear about those events from Frost? Might the story’s hero be a composite of Frost and other men with similar war records? Can we use the story’s details to fill out Frost’s bare-bones pension application, or must we assume that the author used a lot of literary license? Those were questions that Jocelyn Gould of Boston National Historical Park and I started discussing earlier this month.

The easiest place to find “The Young Provincial” now is at the end of this volume of The Complete Writings of Nathaniel Hawthorne, published in 1900. The picture above shows Hawthorne in 1841, or about eleven years after “The Young Provincial” was published. By then he had become locally known for his short stories, many based on New England history.

TOMORROW: But this story is not actually by Hawthorne.

One of those pieces was titled “The Young Provincial,” and it began:

“Now, father, tell us all about the old gun,” were the words of one of a number of children, who were seated around the hearth of a New England cottage. The old man sat in an arm-chair at one side of the fireplace, and his wife was installed in one of smaller dimensions on the other. The boys, that they might not disturb the old man’s meditations, seemed to keep as much silence as was possible for individuals of their age; the fire burned high, with a sound like that of a trumpet, and its blaze occasionally shone on an old rifle which was suspended horizontally above the mantel.Of course, the Revolutionary-era gun above a mantel in a New England cottage wouldn’t have been a rifle but a musket.

The story the old man tells those boys begins with him as a youth in “Tewksbury, a small town in Middlesex county.” He and the other “younger men of our village” formed a minuteman company. The story says: “Perhaps if you accent the last syllable of that word minute, it would better describe a considerable portion of our number, of whom I was one.”

The narrator of the “Young Provincial” describes experiences that closely parallel those of Jacob Frost, quoted yesterday, except in a much more elevated language. This is how Frost’s pension application of 1832 discussed the Battle of Bunker Hill:

[He] was in the battle and was then severely wounded in the hip, and entirely disabled, and he laid among the wounded until the day after the battle—when he was taken up by the British & carried to Boston & there kept a prisonerThe Token story says:

As soon as Boston was invested, we heard that our services were called for, and nothing more was wanted to fill the ranks of the army. I arrived at the camp the evening before the battle of Bunker Hill. Though weary with the march of the day, I went to the hill upon which our men were throwing up the breastwork in silence, and happened to reach the spot just as the morning was breaking in the sky. It was clear and calm; the sky was like pearl, the mist rolled lightly from the still water, and the large vessels of the enemy lay quiet as the islands.Like Jacob Frost, the “Young Provincial” narrator is kept in the Boston jail for months, then transported to Nova Scotia in March 1776. He and five other men break out of their new prison on a night that’s literally described as “dark and stormy.” He struggles through the wilderness toward Massachusetts, benefiting from strangers’ kindness. At last he arrives in Tewksbury on a Sunday.

Never shall I forget the earthquake-voice with which that silence was broken. A smoke like that of a conflagration burst from the sides of the ships, and the first thunders of the revolutionary storm rolled over our heads. The bells of the city spread the alarm, the lights flashed in a thousand windows, the drums and trumpets mustered their several bands, and the sounds, in their confusion, seemed like an articulate voice foretelling the strife of that day.

We took our places mechanically, side by side, behind the breastwork, and waited for the struggle to begin. We waited long and in silence. There was no noise but of the men at the breastwork strengthening their rude fortifications. We saw the boats put off from the city, and land the forces on the shore beneath our station. Still there was silence, except when the tall figure of our commander moved along our line, directing us not to fire until the word was given.

For my part, as I saw those gallant forces march up the hill in well ordered ranks, with the easy confidence of those who had been used to victory, I was motionless with astonishment and delight. I thought only on their danger, and the steady courage with which they advanced to meet it, the older officers moving with mechanical indifference, the younger with impatient daring. Then a fire blazed along their ranks, but the shot struck in the redoubt or passed harmlessly over our heads. Not a solitary musket answered, and if you had seen the redoubt, you would have said that some mighty charm had turned all its inmates to stone.

But when they stood so near us that every shot would tell, a single gun from the right was the signal for us to begin, and we poured upon them a fire, under which a single glance, before the smoke covered all, showed us their columns reeling like some mighty wall which the elements are striving to overthrow. As the vapor passed away, their line appeared as if a scythe of destruction had cut it down, for one long line of dead and dying marked the spot where their ranks had stood.

Again they returned to the charge; again they were cut down; and then the heavy masses of smoke from the burning town added magnificence to the scene. By this time my powder-horn was empty, and most of those around me had but a single charge remaining. It was evident that our post must be abandoned, but I resolved to resist them once again.

They came upon us with double fury. An officer happened to be near me; raising my musket, and putting all my strength into the blow, I laid him dead at my feet. But, meantime, the British line passed me in pursuit of the flying Americans, and thus cut off my retreat; one of their soldiers fired, and the ball entered my side. I fell, and was beaten with muskets on the head until they left me for dead upon the field.

When I recovered, the soldiers were employed in burying their dead. An officer inquired if I could walk; but finding me unable, he directed his men to drag me by the feet to their boats, where I was thrown in, fainting with agony, and carried with the rest of the prisoners to Boston. One of my comrades, who saw me fallen, returned with the news to my parents. They heard nothing more concerning me, but had no doubt that I was slain.

I went to my father’s door, and entered it softly. My mother was sitting in her usual place by the fireside, though there were green boughs instead of fagots in the chimney before her. When she saw me, she gave a wild look, grew deadly pale, and making an ineffectual effort to speak to me, fainted away. With much difficulty I restored her, but it was long before I could make her understand that the supposed apparition was in truth her son whom she had so long mourned for as dead.Again, Jacob Frost’s 1832 account said simply that “he finally arrived at his residence in said Tewksbury the last of September 1776”—which was in fact a Monday.

My little brother had also caught a glimpse of me, and with that superstition which was in that day so much more common than it is in this, he was sadly alarmed. In his fright he ran to the meeting-house to give the alarm; when he reached that place, the service had ended, and the congregation were just coming from its doors. Breathless with fear, he gave them his tidings, losing even his dread, in that moment, for the venerable minister and the snowy wigs of the deacons.

Having told them what he had seen, they turned, with the whole assembly after them, towards my father's house; and such was their impatience to arrive at the spot, that minister, deacons, old men and matrons, young men and maidens, quickened their steps to a run.

Never was there such a confusion in our village. The young were eloquent in their amazement, and the old put on their spectacles to see the strange being who had thus returned as from the dead.

“The Young Provincial” thus seems to be an elevated version of Jacob Frost’s experiences. But did the author really hear about those events from Frost? Might the story’s hero be a composite of Frost and other men with similar war records? Can we use the story’s details to fill out Frost’s bare-bones pension application, or must we assume that the author used a lot of literary license? Those were questions that Jocelyn Gould of Boston National Historical Park and I started discussing earlier this month.

The easiest place to find “The Young Provincial” now is at the end of this volume of The Complete Writings of Nathaniel Hawthorne, published in 1900. The picture above shows Hawthorne in 1841, or about eleven years after “The Young Provincial” was published. By then he had become locally known for his short stories, many based on New England history.

TOMORROW: But this story is not actually by Hawthorne.

Monday, July 17, 2017

Jacob Frost’s Revolutionary War

On 13 Sept 1832, an eighty-year-old man from Norway, Maine, named Jacob Frost signed an affidavit describing his experiences during the Revolutionary War.

Frost’s statement, part of his plea for a federal government pension, said:

In a separate 1832 document, Frost added:

TOMORROW: The literary version.

(The photograph above, courtesy of Classic New England, shows the Brown Tavern on Main Street in Tewksbury, built in 1740. The prominent porch is a later addition, as is the bank branch inside.)

Frost’s statement, part of his plea for a federal government pension, said:

on the 19th day of April 1775, on the alarm of the enemys being on their march from Boston to Lexington, at Tewksbury in the State of Massachusetts, his then residence, he then being a minute man, he marched to Concord in the company commanded by Capt. John Trull of the Massachusetts militia and pursued the enemy to Boston and he immediately enlisted at Cambridge near Boston for a term of eight months, in the company commanded by Capt. Benjamin Walker, in the regiment commanded by Col. Ebenezer Bridge,The Nova Scotia diarist Simeon Perkins wrote on 1 April that “The Centurion man of war is off the harbour.”

and was employed on the night previous to the battle of Bunker Hill on the 17th. Day of June 1775, in throwing up breast works—was in the battle and was then severely wounded in the hip, and entirely disabled, and he laid among the wounded until the day after the battle—when he was taken up by the British & carried to Boston & there kept a prisoner until March 1776, at which time the British evacuated Boston—when he was put on board a British man of war ship, called the Centurian—& carried in Irons to Halifax in Nova Scotia—

and there kept in prison untill the 21st. of June 1776, when he with some others found means to escape from prison, & wandered almost without clothes & entirely without money through the woods, till he finally arrived at his residence in said Tewksbury the last of September 1776, being one year & five months absent from his enlistment aforesaid until his return to his home.That certificate, dated 29 Aug 1788, stated that Frost, then aged thirty-five, had been disabled by “one Musket ball, through his left hip bone.” He was awarded a pension of 15 shillings per month.

In the month of July 1779 [actually 1780] he again enlisted at Tewksbury aforesaid for the term of three months, as a private in the company commanded by Capt Amos Foster, and was immediately appointed a sergeant, said company was attached to the regiment commanded by Colo. [John] Jacobs, and was marched to Rhode Island where he served said three months—and was there verbally discharged—

He further represents that he is an Invalid Pensioner, as will appear by the certificate hereunto annexed—

In a separate 1832 document, Frost added:

during the period of three months, that I served as orderly sargeant in the Company commanded by Capt. Amos Foster in Col. Jacobs regiment, on Rhode Island in the year A.D. 1779—the orderly Sargeant was appointed to act as a Lieut. in consequence of the absence of one of the Lieuts—and I was thereupon appointed to fill the vacancy and served the term of three months in that capacity—and I further declare that I did not receive a warrant from any officer, but acted without one.Other veterans attested to Frost’s work as the company’s orderly sergeant.

TOMORROW: The literary version.

(The photograph above, courtesy of Classic New England, shows the Brown Tavern on Main Street in Tewksbury, built in 1740. The prominent porch is a later addition, as is the bank branch inside.)

Sunday, July 16, 2017

“The Road to Concord” Ends in Stow, 20 July

On Thursday, 20 July, I’ll speak about The Road to Concord at the Randall Library in Stow, Massachusetts.

For this talk I plan to stress the end of the story, as Gen. Thomas Gage strove to find the cannon that the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was accumulating in the countryside—particularly in Concord.

On 29 Oct 1774, that congress appointed Henry Gardner (1731-1782) of Stow as its “receiver general”—the shadow treasurer for a shadow government. The congress asked towns to send Gardner all the taxes they collected for Massachusetts instead of sending them to Harrison Gray, the royal government’s treasurer in Boston.

In 1907 Edward Everett Hale wrote for the Massachusetts Historical Society, “It would seem as if Henry Gardner might be called the first person who by public act was instructed to commit high treason against the King.”

Be that as it may, Gardner was responsible for managing payments for the cannon, carriages, and artillery equipment that the congress bought over the months before the war. Given how the economy worked, he may simply have kept track of the debts that tradesmen or wealthy Patriot merchants were accruing. Many towns apparently chose to keep their tax collections themselves rather than forwarding them on to either side.

Stow has another link to the story in The Road to Concord. It looks like that town was the farthest west that the Boston militia artillery company’s four brass cannon traveled in 1775. The town’s website says, “Cannon were hidden in the woods surrounding the Lower Common, gunpowder and other armaments in the Meeting House and a small powderhouse on Pilot Grove Hill.” I look forward to seeing those sites.

This talk will start at 7:00 P.M. at the Randall Library, 19 Crescent Street in Stow. It is free and open to the public. I’ll have copies of The Road to Concord and other books available for sale and signing.

For this talk I plan to stress the end of the story, as Gen. Thomas Gage strove to find the cannon that the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was accumulating in the countryside—particularly in Concord.

On 29 Oct 1774, that congress appointed Henry Gardner (1731-1782) of Stow as its “receiver general”—the shadow treasurer for a shadow government. The congress asked towns to send Gardner all the taxes they collected for Massachusetts instead of sending them to Harrison Gray, the royal government’s treasurer in Boston.

In 1907 Edward Everett Hale wrote for the Massachusetts Historical Society, “It would seem as if Henry Gardner might be called the first person who by public act was instructed to commit high treason against the King.”

Be that as it may, Gardner was responsible for managing payments for the cannon, carriages, and artillery equipment that the congress bought over the months before the war. Given how the economy worked, he may simply have kept track of the debts that tradesmen or wealthy Patriot merchants were accruing. Many towns apparently chose to keep their tax collections themselves rather than forwarding them on to either side.

Stow has another link to the story in The Road to Concord. It looks like that town was the farthest west that the Boston militia artillery company’s four brass cannon traveled in 1775. The town’s website says, “Cannon were hidden in the woods surrounding the Lower Common, gunpowder and other armaments in the Meeting House and a small powderhouse on Pilot Grove Hill.” I look forward to seeing those sites.

This talk will start at 7:00 P.M. at the Randall Library, 19 Crescent Street in Stow. It is free and open to the public. I’ll have copies of The Road to Concord and other books available for sale and signing.

Saturday, July 15, 2017

Col. Putnam and the Cannon Balls

As shown by postings like this one, I keep my eyes peeled for stories of Continental soldiers during the siege of Boston

picking up British cannon balls for reuse.

Here’s one variation that appeared in the Pennsylvania Evening Post on 14 Sept 1775 in a section on news from London. It was most likely printed in a London newspaper that, at least that early in the war, supported the American cause.

However, I haven’t found any such tricks in first-hand descriptions of the fight from Massachusetts, either newspaper accounts or letters. The story fits a common “crafty Yankees” trope. I’m not convinced it actually happened.

picking up British cannon balls for reuse.

Here’s one variation that appeared in the Pennsylvania Evening Post on 14 Sept 1775 in a section on news from London. It was most likely printed in a London newspaper that, at least that early in the war, supported the American cause.

July 10. We hear Gen. [Israel] Putnam, who distinguished himself last war under Gen. [Jeffery] Amherst, by his ingenious inventions and invincible courage, having nearly expended his cannon ball before the King’s schooner [H.M. S. Diana] surrendered, took this method to get more from the Somerset in Boston harbour:This item was reprinted in New York’s Constitutional Gazette newspaper and thence in Frank Moore’s 1850s compilation Diary of the American Revolution.

He ordered parties, consisting of about two or three of his men, to shew themselves on the top of a certain sandy hill, near the place of action, in sight of the man of war, but at a great distance, in hopes that the Captain would be fool enough to fire at them.

It had the desired effect, and so heavy a fire ensued from this ship and others, that the country round Boston thought the town was attacked. By this means he obtained several hundred balls, which were easily taken out of the sand, and much sooner than he could have sent to the head-quarters for them.

Other accounts say, that towards the close of the day he ordered meal bags to be filled with straw, and set up with hats on, and guns shouldered, which produced the desired effect.

However, I haven’t found any such tricks in first-hand descriptions of the fight from Massachusetts, either newspaper accounts or letters. The story fits a common “crafty Yankees” trope. I’m not convinced it actually happened.

Friday, July 14, 2017

EXTRA: A Projectile from the Plains of Abraham Pops Up

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported:

The C.B.C. report includes a photograph of the excavation workers gathered around the artifact before it was rendered harmless.

A cannonball fired by the British during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759 has been unearthed at a building site in Old Quebec.Technically, I think the gunpowder inside makes this a mortar shell, not a cannonball. But such distinctions wouldn’t matter if someone loses an eye.

The rusted, 90-kilogram projectile was unearthed during excavation work last week at the corner of Hamel and Couillard streets and still contained a charge and gunpowder.

The work crew that found the ball picked it up and gathered around it for photographs, unaware that it was still potentially explosive.

Municipal authorities were contacted, and archeologist Serge Rouleau was called in.

Rouleau brought the cannonball back to his home, and noticed it still contained a charge.

The C.B.C. report includes a photograph of the excavation workers gathered around the artifact before it was rendered harmless.

When Jefferson Investigated the Storming of the Bastille

Since this is Bastille Day, I’m linking to Sara Georgini’s article on for the Smithsonian magazine, “How the Key to the Bastille Ended Up in George Washington’s Possession.”

Here’s a taste:

Here’s a taste:

On July 14, 1789, a surge of protesters stormed the medieval fortress-turned-prison known as the Bastille. Low on food and water, with soldiers weary from repeated assault, Louis XVI’s Bastille was a prominent symbol of royal power—and one highly vulnerable to an angry mob armed with gunpowder. From his two-story townhouse in the Ninth Arrondissement, the Virginian Thomas Jefferson struggled to make sense of the bloody saga unspooling in the streets below.I saw that key a couple of years ago; here’s that little story.

He sent a sobering report home to John Jay, then serving as Secretary for Foreign Affairs, five days after the Bastille fell. Even letter-writing must have felt like a distant cry—since the summer of 1788, Jefferson had faithfully dispatched some 20 briefings to Congress, and received only a handful in reply. In Jefferson’s account, his beloved Paris now bled with liberty and rage. Eyeing the narrowly drawn neighborhoods, Jefferson described a nightmarish week. By day, rioters pelted royal guards with “a shower of stones” until they retreated to Versailles. At evening, trouble grew. Then, Jefferson wrote, protesters equipped “with such weapons as they could find in Armourer’s shops and private houses, and with bludgeons…were roaming all night through all parts of the city without any decided and practicable object.”

Yet, despite his local contacts, Jefferson remained hazy on how, exactly, the Bastille fell. The “first moment of fury,” he told Jay, blossomed into a siege that battered the fortress that “had never been taken. How they got in, has as yet been impossible to discover. Those, who pretend to have been of the party tell so many different stories as to destroy the credit of them all.” Again, as Jefferson and his world gazed, a new kind of revolution rewrote world history. Had six people led the last charge through the Bastille’s tall gates? Or had it been 600? (Historians today place the number closer to 900.)

In the days that followed, Jefferson looked for answers. By July 19, he had narrowed the number of casualties to three. (Modern scholars have raised that estimate to roughly 100.) Meanwhile, the prison officials’ severed heads were paraded on pikes through the city’s labyrinth of streets. With the Bastille in ruins, the establishment of its place in revolutionary history—via both word and image—spun into action. Like many assessing what the Bastille’s fall meant for France, Thomas Jefferson paid a small sum to stand amid the split, burnt stone and view the scene. One month later, Jefferson returned. He gave the same amount to “widows of those who were killed in taking the Bastille.”

At least one of Jefferson’s close friends ventured into the inky Paris night, bent on restoring order. Major General Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, a mainstay at Jefferson’s dinner table, accepted a post as head of the Paris National Guard. As thanks, he was presented with the Bastille key.

Thursday, July 13, 2017

John Pigeon’s Petulance and Property

I was tracing the political career of John Pigeon, a Boston merchant who retired to Newton a few years before the Revolution. In the early months of 1775 he went from clerk of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress’s committee of safety to commissary of stores to commissary general of the Massachusetts army.

And within two months Pigeon decided that job was too much for him. On 20 June he petitioned to be allowed to resign. The congress instead adopted this recommendation from a committee:

Three days later, at Pigeon’s request, the congress appointed a committee to examine his account books. This was a common way to respond to accusations of malfeasance or other criticism.

And Pigeon was getting criticism. After the Battle of Bunker Hill the army had spread out, putting more men on Prospect and Winter Hills to prevent any redcoats from charging off the Charlestown peninsula. That made it harder to supply every regiment. On 30 June Gen. Artemas Ward wrote to Pigeon:

But by then, apparently, Pigeon had damaged his reputation with his colleagues. On 9 August James Warren, president of the congress, told John Adams, “his temper is so petulant, that he has been desirous of quitting for some time, and, indeed, I have wished it.”

The Continental Congress’s takeover of the New England army offered a way to resolve this situation. On 19 July the Congress in Philadelphia appointed Joseph Trumbull, politically well connected and already in camp as commissary for the Connecticut troops, to be commissary general of the whole army. On 12 August the Massachusetts General Court responded by passing this resolve:

By November 1775 the Massachusetts government was treating Richard Devens, a reliable member of the committee of safety from Charlestown, as its head commissary. No one’s found a date for his official commission; Devens seems to have slid into the office after working on other assignments, but by the end of the year he had the title.

And on 9 December, the legislature had to resolve:

John and Jane Pigeon’s only daughter, Patience, died in Newton in 1777 at age twenty-four. Their sons John, Jr., and Henry both married in 1790 and started having children. Then Henry died in 1799; John, Sr., in 1800; and John, Jr., in 1801. Widow Jane Pigeon passed away in 1808.

Pigeon’s estates in Newton became the town’s poor farm for a while. But one grandson born in 1799, the Rev. Charles Dumaresq Pigeon, remembered that property fondly. He bought land in the “Riverside” area in 1846, convinced a railroad to build a stop there, and recruited other clergymen to retire nearby. The result was the genteel suburb that the Rev. Mr. Pigeon dubbed Auburndale.

And within two months Pigeon decided that job was too much for him. On 20 June he petitioned to be allowed to resign. The congress instead adopted this recommendation from a committee:

Resolved, That Mr. John Pigeon, commissary general, requesting a dismission from his said office, being under a mistake, have liberty to withdraw his petition; that the conduct of said commissary general in his office, has been such as to merit the approbation of this Congress, and of the public in general; and that said John Pigeon be desired to attend his business as commissary general in the service of this province.The legislature agreed to assist Pigeon by appointing a deputy commissary for every regiment, adding considerably to its payroll. On 25 June Pigeon told the committee of safety that he also needed a “supervisor” near each of the main camps of the American army, in Cambridge and Roxbury. Men