Shortly after the establishment of the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates reported to Commander-in-Chief George Washington that “the sick suffered much for want of good female Nurses.” Gen. Washington then asked Congress for “a matron to supervise the nurses, bedding, etc.,” and for nurses “to attend the sick and obey the matron’s orders.” A plan was submitted to the Second Continental Congress that provided one nurse for every ten patients and provided “that a matron be allotted to every hundred sick or wounded.”Though I’d studied Washington’s work in Cambridge in 1775–76, that first quotation was new to me. I’m always interested in more information, so I dug deeper, seeking more definite dates.

Those statements and quotations are echoed in other army webpages and textbooks about the history of nursing. After all, they come from the army itself.

Some of those overviews put Gates’s report on 14 June 1775 instead of “Shortly after” that date. But that timing wouldn’t make sense. As the original passage above states, the Congress created the Continental Army on 14 June—implicitly, by authorizing the recruitment of riflemen from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland. Washington wasn’t commissioned commander-in-chief for another couple of days.

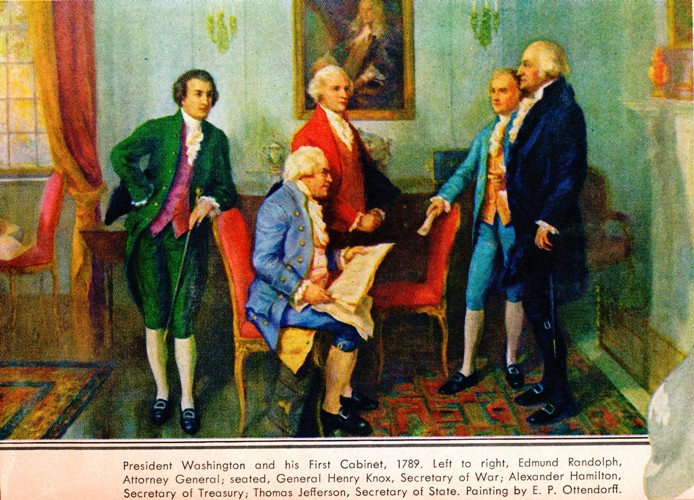

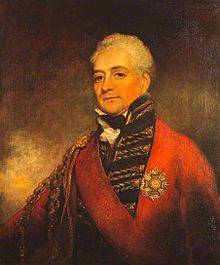

As for Gates (shown above), he learned of his appointment as adjutant general (with the rank of brigadier general) on 21 June, and he reached Cambridge on 9 July. So at what point “Shortly after” 14 June would he have made that quoted statement?

Fortunately, the specificity of the quotations makes it easy to look them up on Founders Online, which includes all known writing to and from George Washington during the war. Gates’s reports to Washington and the commander-in-chief’s requests to the Congress all appear there.

Yet none of the quoted phrases comes up in a Founders Online search.

TOMORROW: Real sources and real dates.