“The Case of the poor Boy, Calvin Piper”

In 1758, a young man named John Piper bought farmland in Bolton. He married around the same time, and from 1759 to 1765 Mary Piper had four children in Bolton. The third was a boy named Calvin, born 11 Apr 1763.

In 1764 John Piper, alongside his brothers and several neighbors, started buying farmland to the west in the town of Templeton. The next year, John moved his family onto sixty acres there.

After another few years, the Piper family moved again, this time back east to Westborough. A family genealogist found no evidence John Piper bought land in that town and guessed he “had decided to rely on his work as a tanner to support the family.” It’s also possible that the Pipers were now poor enough they had to work on other people’s land.

On 29 Apr 1774, Westborough’s minister, the Rev. Ebenezer Parkman, wrote in his diary:

That summer, many Massachusetts towns became even more roiled in imperial politics than they were already. On 1 August, Westborough had a town meeting about “Subscribing the Agreement” and “bearing of the Charge of the Congress.”

On that same Monday, Parkman wrote:

Delirium, vomiting, sleepiness—those are all symptoms of a serious head injury. Parkman was not optimistic (but then he rarely seems to have been). The next day, the minister visited the house of militia lieutenant Joseph Baker “to see young Piper”—despite his injury, the boy had been moved. Parkman wrote, “He is no better. Prayed with him.”

On Saturday morning, a coterie of rural surgeons came to Baker’s house. In addition to the local Dr. Hawes, Parkman also listed Charles Russell of Lincoln (politically a Loyalist, but still valued as a doctor), Edward Flynt of Shrewsbury, and “a Number of Doctors besides being there on the Case of the poor Boy, Calvin Piper.”

Fortunately, there were now good signs. The minister reported that the boy “last Evening began to recover his senses and to Speak—and is this morning composed and utters himself pertinently.”

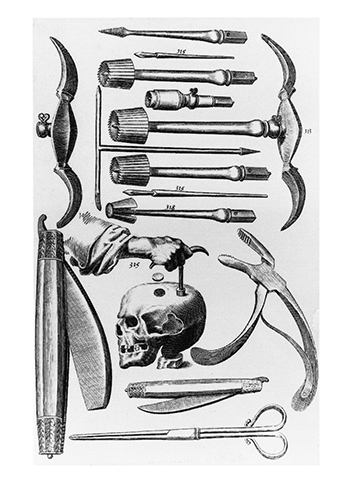

Still, those doctors had come prepared to trepan the kid—to drill a hole in Calvin’s skull to remove fluids and relieve pressure on his brain. They had no doubt brought their drills and other tools. It would have been a shame not to use any of that equipment.

TOMORROW: The operation and the aftermath.

In 1764 John Piper, alongside his brothers and several neighbors, started buying farmland to the west in the town of Templeton. The next year, John moved his family onto sixty acres there.

After another few years, the Piper family moved again, this time back east to Westborough. A family genealogist found no evidence John Piper bought land in that town and guessed he “had decided to rely on his work as a tanner to support the family.” It’s also possible that the Pipers were now poor enough they had to work on other people’s land.

On 29 Apr 1774, Westborough’s minister, the Rev. Ebenezer Parkman, wrote in his diary:

At Eve came Mr. John Piper who is newly come to live among us, and asks the privilege to communicate with us, as also that his Wife Mary, may; they being Members of the Church in Templeton.The Pipers were trying to fit into the Westborough community and congregation.

That summer, many Massachusetts towns became even more roiled in imperial politics than they were already. On 1 August, Westborough had a town meeting about “Subscribing the Agreement” and “bearing of the Charge of the Congress.”

On that same Monday, Parkman wrote:

Martin Piper, a Lad in his 12th Year, was thrown by a Colt, and his Head came down on a Rock, nigh Mr. Newtons. He was carryed in there. It was feared to be a mortal Blow. Mr. Newton came in haste for me. I went. He was delirious. Dr. [James] Hawes soon blooded him. He bled well. Vomited Several Times — inclined to sleep; when any thing was given him, he cryed out bitterly, but could not speak. I prayed with him. What a Warning! Especially to Youth! But how great the Mercy he was not killed! His parents much distressed.As subsequent journal entries make clear, this was Calvin Piper. In his distress, and not knowing the family well, the minister mistakenly called him “Martin” (after another Protestant leader?).

Delirium, vomiting, sleepiness—those are all symptoms of a serious head injury. Parkman was not optimistic (but then he rarely seems to have been). The next day, the minister visited the house of militia lieutenant Joseph Baker “to see young Piper”—despite his injury, the boy had been moved. Parkman wrote, “He is no better. Prayed with him.”

On Saturday morning, a coterie of rural surgeons came to Baker’s house. In addition to the local Dr. Hawes, Parkman also listed Charles Russell of Lincoln (politically a Loyalist, but still valued as a doctor), Edward Flynt of Shrewsbury, and “a Number of Doctors besides being there on the Case of the poor Boy, Calvin Piper.”

Fortunately, there were now good signs. The minister reported that the boy “last Evening began to recover his senses and to Speak—and is this morning composed and utters himself pertinently.”

Still, those doctors had come prepared to trepan the kid—to drill a hole in Calvin’s skull to remove fluids and relieve pressure on his brain. They had no doubt brought their drills and other tools. It would have been a shame not to use any of that equipment.

TOMORROW: The operation and the aftermath.

No comments:

Post a Comment