“My affectionate bosom friend will be with me”

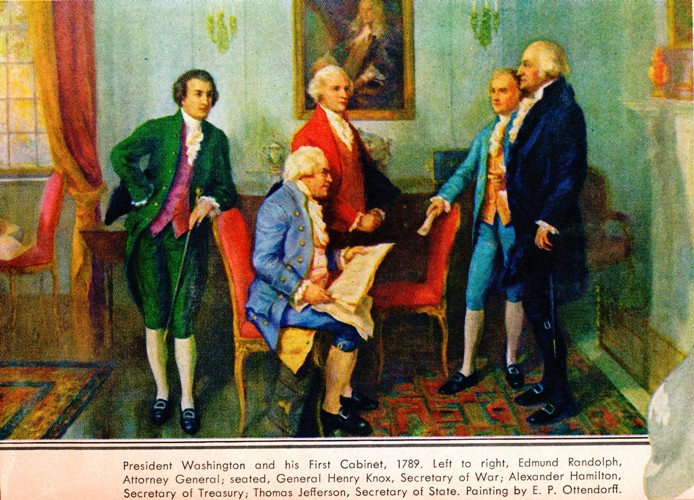

I told the story of Elizabeth and Edmund Randolph’s distress over a miscarriage through Edmund’s correspondence with James Madison.

Since the Randolphs were together at the time, there were of course no letters between them. But I find that Edward had written to Elizabeth just before he came home from New York, telling her he was moving the family to the capital for his job, and he knew she wouldn’t be happy about that.

Edmund wrote on 14 Feb 1790:

It shows that Elizabeth was already reluctant to make a big move, even before her pregnancy went awry. It also states exactly when Randolph had promised to be back at George Washington’s side while the new federal governmet took shape. The attorney general missed that deadline by weeks, so no wonder he was anxious about what the President would say.

At the same time, this letter shows how Edmund was still gushing with affection for Elizabeth fourteen years after their marriage—though also cajoling her into what he wanted.

TOMORROW: The farewell.

Since the Randolphs were together at the time, there were of course no letters between them. But I find that Edward had written to Elizabeth just before he came home from New York, telling her he was moving the family to the capital for his job, and he knew she wouldn’t be happy about that.

Edmund wrote on 14 Feb 1790:

My dearest Betsy:That text is quoted from Omitted Chapters of History Disclosed in the Life and Papers of Edmund Randolph by Moncure Daniel Conway.

I can now inform you with certainty that I shall return to Virginia to bring my treasures thence; and indeed if the importunity of the President with me to stay had not been overwhelming I should not have hesitated about a resignation. . . .

The President insists, and I have promised to be here by the 20th April precisely. We must therefore without fail begin our journey on the first day of April. . . .

I am afraid it may be inconvenient and indeed painful to you, my dear wife, but I candidly tell you that I shall not be able to return to accompany you after the present trip. Let us not, I beseech you, be longer separated than the strange vicissitudes of life render indispensable. Prepare yourself and the girls for the trip. I shall provide the conveyances. . . .

My two chief anxieties on this subject are the difficulty of your travelling in your present situation [i.e., pregnancy], and the preference you would give to being confined in Virginia rather than here. But what am I to do, thou dearest object of my soul? I will consent to any thing but an absence from you. I will provide you with a gentle and easy passage.

I undergo a mixture of sensations when I think of our new plans. But it comforts me to think that my affectionate bosom friend will be with me, and that I really believe she may be happy. Until we meet, keep in remembrance my never-failing love for the best of women. Adieu, my dearest girl.

It shows that Elizabeth was already reluctant to make a big move, even before her pregnancy went awry. It also states exactly when Randolph had promised to be back at George Washington’s side while the new federal governmet took shape. The attorney general missed that deadline by weeks, so no wonder he was anxious about what the President would say.

At the same time, this letter shows how Edmund was still gushing with affection for Elizabeth fourteen years after their marriage—though also cajoling her into what he wanted.

TOMORROW: The farewell.

No comments:

Post a Comment