Friday, 17 June 1774, turned out to be the last day the Massachusetts assembly met under the Crown.

Before Gov. Thomas Gage shut them down, Samuel Adams and his allies used that session to authorize a delegation from the colony to the Continental Congress, as I’ve just recounted.

On the same day, there was the continuation of a town meeting in Boston. Some of that port’s merchants had started to grumble against the Whigs’ insistence that no one should pay for the tea destroyed in December (or in March, for that matter).

Adams was officially the moderator of that ongoing meeting. Expecting “a warm engagement” with the conciliatory party, Dr. Joseph Warren urged Adams to return to Boston to wield the gavel. But he was was stuck “at Salem, attending the Business of the General Court.”

At 10:00 A.M., the meeting began in Faneuil Hall. The first order of business was appointing a temporary moderator in Adams’s place. The gathering’s unanimous choice was James Bowdoin, a wealthy merchant, learned man, and genteel political leader for the Whigs.

A committee of three men went to Bowdoin’s home near Beacon Hill. He wasn’t there.

The meeting then selected merchant John Rowe to moderate. This was an unusual choice because Rowe was not a Whig stalwart. Nor was he really a Loyalist stalwart. He was a “trimmer,” adjusting his political sails according to the prevailing winds and what looked most advantageous to his business.

Perhaps the public remembered Rowe’s remark back in December about mixing tea and saltwater—the first public suggestion of that method of resolving the standoff over the East India Company cargo. Secretly Rowe appears to have regretted that remark and tried to keep a low profile afterward. So he would hardly want to chair a town meeting making controversial decisions.

In his diary Rowe wrote: “I was much engaged & therefore did not accept.” But he added a remark showing his real attitude: “The People at present seem very averse to Accommodate Matters. I think they will Repent of their Behaviour, sooner or later.”

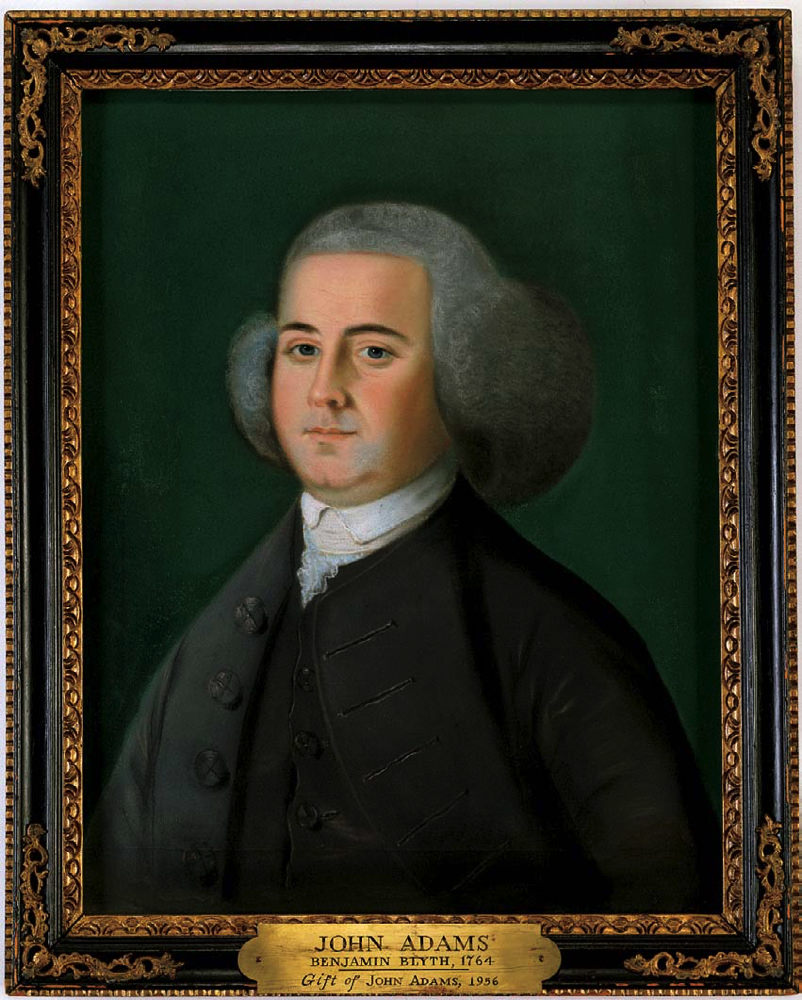

Back at Faneuil Hall, the gathering moved on to vote for a gentleman who had never moderated the Boston town meeting before. In fact, he later said he usually kept away from town meetings. But he had represented Boston for one year in the Massachusetts General Court.

This was John Adams. Per the record, “a Committee of three Gentlemen” went to him with news of their choice, and Adams “gave his Attendance accordingly.”

TOMORROW: John Adams in the chair.

History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

▼

Sunday, June 30, 2024

Saturday, June 29, 2024

“Their Orders were to keep the Door fast”

On Friday, 17 June 1774, inside the Salem courthouse, the Massachusetts assembly discussed sending five men to what would become the First Continental Congress.

According to the official tally, there were 129 members present. That was only about half the number of representatives that towns had elected in May, but the royal governor’s order to move the legislator to Salem had probably cut attendance. (And truth be told, the Massachusetts House rarely saw full attendance anyway.)

Of those 129 representatives, only twelve voted against the proposal. While some of the rest may have abstained, that number suggests that the Loyalist party commanded only a tenth of the chamber. Though there were lots of political arguments in Massachusetts during these tears, there were few close votes.

Nonetheless, Gov. Thomas Gage had a power stronger than democracy. Under the charter of 1692, he could simply declare the legislative session over, halting all bills.

As soon as he learned what was happening in the House, Gage sent the provincial secretary, Thomas Flucker (shown above), to Salem with just such an order.

The 20 June Boston Gazette reported:

The Massachusetts General Court was officially dissolved. Yet the assembly had officially passed the resolutions sending delegates to the congress and seeking money to pay for that trip. That packet of resolutions was quickly sent to the newspapers, which printed it before Gov. Gage’s proclamation.

TOMORROW: Meanwhile, in Faneuil Hall…

According to the official tally, there were 129 members present. That was only about half the number of representatives that towns had elected in May, but the royal governor’s order to move the legislator to Salem had probably cut attendance. (And truth be told, the Massachusetts House rarely saw full attendance anyway.)

Of those 129 representatives, only twelve voted against the proposal. While some of the rest may have abstained, that number suggests that the Loyalist party commanded only a tenth of the chamber. Though there were lots of political arguments in Massachusetts during these tears, there were few close votes.

Nonetheless, Gov. Thomas Gage had a power stronger than democracy. Under the charter of 1692, he could simply declare the legislative session over, halting all bills.

As soon as he learned what was happening in the House, Gage sent the provincial secretary, Thomas Flucker (shown above), to Salem with just such an order.

The 20 June Boston Gazette reported:

His Excellency the Governor having directed the Secretary to acquaint the two Houses it was his Excellency’s pleasure the General Assembly should be dissolved and to declare the same dissolved accordingly; the Secretary went to the Court House and finding the Door of the Representatives Chamber locked, directed the Messenger to go in, and acquaint the Speaker [Thomas Cushing] that the Secretary had a message from his Excellency to the Hon. House, and desired he might be admitted to deliver it;According to John Sanderson’s profile of Samuel Adams, published about half a century later:

The Messenger soon returned, and said he had acquainted the Speaker therewith, who mentioned it to the House, and their Orders were to keep the Door fast:

The door keeper seemed uneasy at his charge, and wavering with regard to the performance of the duty assigned to him. At this critical juncture, Mr. Adams relieved him, by taking the key and keeping it himself.Flucker proceeded with his royal duty, as the newspaper reported:

Whereupon, the following proclamation was published on the stairs leading to the Representatives Chamber, in presence of a Number of Members of the House, and immediately after in Council.To be clear, the Rev. William Gordon wrote that the secretary “read the proclamation upon the steps leading to the representatives’ chamber.” It’s unclear whether this was before or after the assembly’s vote, but the legislators didn’t acknowledge the governor’s proclamation until Adams opened the doors.

The Massachusetts General Court was officially dissolved. Yet the assembly had officially passed the resolutions sending delegates to the congress and seeking money to pay for that trip. That packet of resolutions was quickly sent to the newspapers, which printed it before Gov. Gage’s proclamation.

TOMORROW: Meanwhile, in Faneuil Hall…

Friday, June 28, 2024

“A ministerial member pleaded a call of nature”

The Massachusetts House started its session on Friday, 17 June 1774, at 9:00 A.M.

The first action was a committee report on a land grant, which the legislators read and accepted.

Then came the all-important “Committee appointed to consider the State of the Province.” The House approved a motion “The the Gallaries be clear’d and the Door be shut.”

Ordinarily this step was to keep spectators away from sensitive discussions before official votes, so legislators could speak freely and discuss compromises. In this case, however, House clerk Samuel Adams and his allies also wanted to keep people in.

The Rev. William Gordon recounted:

The designated men were:

At that moment Adams and Cushing were leading the discussion in the chamber. Bowdoin was home sick, Adams was in Boston, and Paine on his way back to Salem from Taunton with fellow legislator Daniel Leonard.

The House then approved paying £500 for those five men’s expenses traveling and staying wherever the congress met. Finally, with a lot more verbiage than I’ll reproduce, the chamber resolved that this “Meeting of Committees” was so important that it urged towns to come up with that £500 outside of the regular tax system in case the Council didn’t get around to approving this bill or the governor vetoed it.

By this time word had reached Gage at the house he rented in Danvers (shown above at its new location). He knew what the General Court was up to.

TOMORROW: The key.

The first action was a committee report on a land grant, which the legislators read and accepted.

Then came the all-important “Committee appointed to consider the State of the Province.” The House approved a motion “The the Gallaries be clear’d and the Door be shut.”

Ordinarily this step was to keep spectators away from sensitive discussions before official votes, so legislators could speak freely and discuss compromises. In this case, however, House clerk Samuel Adams and his allies also wanted to keep people in.

The Rev. William Gordon recounted:

They had their whole plan compleated, prepared their resolves, and then determined upon bringing the business forward. But before they went upon it, the door-keeper was ordered to let no one whatsoever in, and no one was to go out:Inside the Salem courthouse, the committee laid out their recommendations. First, the General Court would appoint five men to represent Massachusetts at an upcoming “Meeting of Committees from the several Colonies on this Continent”—what became known as the Continental Congress.

however, when the business opened, a ministerial member pleaded a call of nature, which is always regarded, and was allowed to go out.

He then ran to give information of what was doing, and a messenger was dispatched to general [Thomas] Gage, who lived at some distance.

The designated men were:

At that moment Adams and Cushing were leading the discussion in the chamber. Bowdoin was home sick, Adams was in Boston, and Paine on his way back to Salem from Taunton with fellow legislator Daniel Leonard.

The House then approved paying £500 for those five men’s expenses traveling and staying wherever the congress met. Finally, with a lot more verbiage than I’ll reproduce, the chamber resolved that this “Meeting of Committees” was so important that it urged towns to come up with that £500 outside of the regular tax system in case the Council didn’t get around to approving this bill or the governor vetoed it.

By this time word had reached Gage at the house he rented in Danvers (shown above at its new location). He knew what the General Court was up to.

TOMORROW: The key.

Thursday, June 27, 2024

“Undertook to carry off Mr. Leonard”

As I’ve been discussing, in the middle of June 1774 Samuel Adams and his Whig colleagues had come up with a plan to have their colony represented at what would be the First Continental Congress.

As I’ve been discussing, in the middle of June 1774 Samuel Adams and his Whig colleagues had come up with a plan to have their colony represented at what would be the First Continental Congress.But to give the Massachusetts General Court time to approve that plan before Gov. Thomas Gage learned about it and shut down the legislature, they needed to get around committee member Daniel Leonard. He had recently moved to the Loyalist side of the political divide.

Besides Leonard, the other representative from Taunton was Robert Treat Paine, one of Adams’s allies. Both Leonard and Paine were lawyers, and on Tuesday, 14 June, the Bristol County court of common pleas was due to sit in their town. The courthouse was quite close to Leonard’s house, in fact.

As Paine described his actions decades later, he told Leonard that

it had been usual for Years past, to adjourn the Common Pleas Court at Taunton which was to set the then next Tuesday in Order that the Members of the General Court from that County might attend the General Court; but that the Neglect of it always gave uneasiness to many persons; especially the Tavern keepers, who from the great Concourse of people Collected there (the days being long & the Season pleasant) reaped great profits &c., &c., & that we might agree to Shorten the Court by Demurrers & Continuances & get back to [the Massachusetts General] Court in Season to attend to all important businessIt was important for politicians to keep local tavern-keepers happy, after all. They were influential men at election times.

But Paine revealed his real motivation when he wrote: “the writer hereof Undertook to carry off Mr. Leonard.”

This maneuver is sometimes described as Paine inducing Leonard to leave Salem just before the crucial legislative vote. But in fact the two men left the previous Saturday, attended the county court for a few days, and even agreed to sit on a county committee to write an address to Gov. Gage.

At the end of the week, Paine and Leonard headed back to the legislature in Salem—“in Season to attend to all important business,” Paine had promised. But Adams’s resolutions were already moving.

TOMORROW: Behind closed doors.

Wednesday, June 26, 2024

“Keep the committee in play, and I will go and make a caucus”

In addition to Robert Treat Paine’s recollection quoted here, the Rev. William Gordon’s early history of the American Revolution offers another peek at the delicate political maneuverings in Salem in June 1774.

Gordon wrote:

First, the Massachusetts House would appoint delegates to a Continental Congress, an idea raised by the Providence town meeting, the Virginia House of Burgesses, and other political allies outside of the colony. The House would also alert all its counterparts of that step and urge them to participate as well.

But then there was the age-old question of how to pay for this. Sending five gentlemen to Philadelphia would cost upwards of £500. Any legislative action involving money, even if it passed the Council, could be vetoed by Gov. Thomas Gage.

The solution was to write a bill authorizing that expenditure of £500 and then adding this clause:

The next problem was how to pass those resolutions through the House. As Paine wrote:

TOMORROW: The Bristol feint.

Gordon wrote:

Mr. Samuel Adams observed, that some of the committee were for mild measures, which he judged no way suited to the present emergency. He conferred with Mr. [James] Warren of Plymouth upon the necessity of giving into spirited measures, and then said, “Do you keep the committee in play, and I will go and make a caucus against the evening; and do you meet me.”Adams and his team came up with a two-step plan.

Mr. Samuel Adams secured a meeting of about five principal members of the house, at the time specified; and repeated his endeavours against the next night; and so as to the third, when they were more than thirty; the friends of administration knew nothing of the matter. The popular leaders took the sense of the members in a private way, and found that they should be able to carry their scheme by a sufficient majority.

First, the Massachusetts House would appoint delegates to a Continental Congress, an idea raised by the Providence town meeting, the Virginia House of Burgesses, and other political allies outside of the colony. The House would also alert all its counterparts of that step and urge them to participate as well.

But then there was the age-old question of how to pay for this. Sending five gentlemen to Philadelphia would cost upwards of £500. Any legislative action involving money, even if it passed the Council, could be vetoed by Gov. Thomas Gage.

The solution was to write a bill authorizing that expenditure of £500 and then adding this clause:

Wherefore this House would recommend, and they do accordingly hereby recommend to the several Towns and Districts within this Province, that each Town and District, raise, collect and pay, to the Honorable THOMAS CUSHING, Esq; of Boston, the Sum of FIVE HUNDRED POUNDS by the Fifteenth Day of August next, agreeable to a List herewith exhibited, being each Town and District’s proportion of said Sum, according to the last Province Tax, to enable them to discharge the important Trust to which they are appointed; they upon their Return to be accountable for the same.Adams’s unofficial caucus managed to formulate that plan without official committee member Daniel Leonard or other Loyalists catching on.

The next problem was how to pass those resolutions through the House. As Paine wrote:

it was Considered that the regular Method was for the Committee on the State of the Province to make report of these doings as their Report; eight of that Committee were then present, but the ninth [Leonard] was known to be adverse to any Such measure & therefore could not be trusted, least the whole should be defeated by the Governor;…If Gov. Gage learned about the measures that the House was discussing, he could use his constitutional authority to shut down the legislature entirely.

TOMORROW: The Bristol feint.

Tuesday, June 25, 2024

Boston’s “party who are for paying for the tea”

June 1774 was a tense time in Boston. At the start of the month the harbor was closed to trade, with Royal Navy warships enforcing that rule.

Army regiments were arriving: the 4th Regiment on 10 June, the 43rd Regiment on 15 June. These troops joined the men Gen. Thomas Gage had brought with him in May.

Many of the town’s merchants, fearing for their livelihood, were trying to devise a way to pay for the East India Company tea destroyed in December, compromising with the Crown and getting back to business.

The “no taxation without representation” crowd thought that would be giving in to an unjust power grab by Parliament.

Just as the Boston Whigs had organized opposition to landing that tea in meetings of “the Body of the People” rather than official town meetings, Boston’s business community had their own big but unofficial gathering.

Merchant John Rowe wrote in his diary on 15 June:

TOMORROW: Back in Salem, a plan comes together.

Army regiments were arriving: the 4th Regiment on 10 June, the 43rd Regiment on 15 June. These troops joined the men Gen. Thomas Gage had brought with him in May.

Many of the town’s merchants, fearing for their livelihood, were trying to devise a way to pay for the East India Company tea destroyed in December, compromising with the Crown and getting back to business.

The “no taxation without representation” crowd thought that would be giving in to an unjust power grab by Parliament.

Just as the Boston Whigs had organized opposition to landing that tea in meetings of “the Body of the People” rather than official town meetings, Boston’s business community had their own big but unofficial gathering.

Merchant John Rowe wrote in his diary on 15 June:

This Evening the Tradesmen of the Town met to Consult on the Distress of this PlaceDr. Joseph Warren reported to Samuel Adams, who was in Salem with the Massachusetts General Court:

There were Upwards of eight hundred at this meeting – they did nothing being much Divided in Sentiment

This afternoon was a meeting of a considerable number of the tradesmen of this town; but, after some altercations, they dissolved themselves without coming to any resolutions, for which I am very sorry, as we had some expectations from the meeting.Back on 30 May, the Boston town meeting had adjourned to Friday, 17 June. Warren wanted Adams back in Boston by then to chair that session. But Adams was busy pulling strings in Salem, and trying to keep those strings invisible from Daniel Leonard.

We are industrious to save our country, but not more so than others are to destroy it. The party who are for paying for the tea, and by that making a way for every compliance, are too formidable.

However, we have endeavored to convince friends of the impolicy of giving way in any single article, as the arguments for a total submission will certainly gain strength by our having sacrificed such a sum as they demand for the payment of the tea.

I think your attendance can by no means be dispensed with next Friday. I believe we shall have a warm engagement. . . .

You will undoubtedly do all in your power to effect the relief of this town, and to expedite a general congress; but we must not suffer the town of Boston to render themselves contemptible, either by their want of fortitude, honesty, or foresight, in the eyes of this and the other colonies.

TOMORROW: Back in Salem, a plan comes together.

Monday, June 24, 2024

“It was known to all but Mr. Leonard”

Robert Treat Paine and Daniel Leonard were Taunton’s two representatives to the Massachusetts General Court in the spring of 1774.

Both Paine and Leonard were Harvard graduates and well regarded lawyers. Both men had, as I mentioned yesterday, courted Sarah White, with Leonard being successful and marrying her.

(Paine finally married Sally Cobb of Taunton in 1770, when he turned thirty-nine and she twenty-six. Losing no time, they had their first child two months later.)

On 9 June 1774, both Paine and Leonard were named to the assembly’s committee of nine members to consider how Massachusetts should respond to the Boston Port Bill.

Looking back after two decades, Paine described that period this way:

TOMORROW: Dr. Warren’s diagnosis.

Both Paine and Leonard were Harvard graduates and well regarded lawyers. Both men had, as I mentioned yesterday, courted Sarah White, with Leonard being successful and marrying her.

(Paine finally married Sally Cobb of Taunton in 1770, when he turned thirty-nine and she twenty-six. Losing no time, they had their first child two months later.)

On 9 June 1774, both Paine and Leonard were named to the assembly’s committee of nine members to consider how Massachusetts should respond to the Boston Port Bill.

Looking back after two decades, Paine described that period this way:

Mr. Leonard was a Gentleman of natural good Sence & Eloquence, polite & of engaging Adress & had been Chosen Several Years as member for the Town of Taunton, on the Idea of his being a firm & able freind to the Opposition in wch. his Town was so determined; but on the prevailing Address & Sollicitation of Govr. [Thomas] Hutchinson he had changed his principles, & considered himself now at Market to make the best of them;Meanwhile, back in Boston some leading merchants were also arguing that the town should pay for the East India Company tea.

all this was well known to the members of the Court & the rest of the Committee more especially to his Colleague the writer hereof; it was therefore considered unsafe for that committee to enter into the consideration of the State of the Province on principles of Opposition while he was present, & as it appeared by the Port bill that the only releif from the Continual Exn. of it was the payment for the Tea that was destroy’d, the Committee turn’d their whole Attention to that;

& as it was known to all but Mr. Leonard, that Another Committee of vastly more importance, form’d from Members of the house of Representatives by their own inclinations was beginning to operate in secret the committee of nine talkd very favourably of paying for the Tea, as a thing not to be compar’d with the Sufferings from the Port Bill:

it would be hard to discribe the Smooth & placid Observations made by Mr. S[amuel]. Adams, Saying that it was an irritating affair, & must be handled Cautiously; that the people must have time to think & form their minds, & that hurrying the matter would certainly create such an Opposition as would defeat the matter;

& many Observations of this kind, all tending to induce Mr. Leonard the Oblique Member of that Committee to think that matters would work terminate in Obedience to the Port Bill were made by Several other Members of the Committee, & then it was Observ’d that it was very hot, & that they had been engag’d in Court all day, & that it was unprofitable to set any longer at that time for the people must have time to bring their minds to a Compromise;

Proceedings of this kind took place on the PM & Evning of three days; as soon as the Committee on the State of the Province was adjournd, all the Members except Mr. Leonard immediately repaird to a retired room where the Self Created Committee before mention’d mett, & being cornpos’d of Such members only as had Signalized themselves in their Opposition to the British Aggressions of Tyrannick Govt., they Shut their Doors & entered freely & fully on all the Subjects of Grievances;…

TOMORROW: Dr. Warren’s diagnosis.

Sunday, June 23, 2024

Daniel Leonard on the Move

Daniel Leonard (1740–1829) was born into a wealthy family in Norton. He went to Harvard College, where he ranked third in the class of 1760 in social prestige, captained a militia company, and was elected valedictorian.

After graduating, Leonard earned his master’s degree and then went into the law. He was a leader among other bright young attorneys like Josiah Quincy, Jr., Francis Dana, and John Trumbull.

In 1767 Leonard married Sarah White, daughter of his legal mentor. Her other suitors had included Robert Treat Paine. Sarah Leonard died young, however, and in 1770 Leonard remarried to Sarah Hamock, daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant, in Trinity Church.

Inheriting his first father-in-law’s legal practice and his second father-in-law’s money, Leonard settled in Taunton. He quickly gained a royal appointment as the King’s Attorney for Bristol County and a seat in the Massachusetts General Court.

In that legislature Leonard worked with the province’s most fervent Whigs. He was on the committee of correspondence and a committee that called for the removal of Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and Chief Justice Peter Oliver.

Around the time of the Boston Tea Party, however, Leonard moved toward the side of the royal government. He said he’d come to distrust the motives of men like Samuel Adams. In February 1774 Leonard voted against impeaching Oliver.

People said Gov. Hutchinson had lured Leonard over to the Crown. Taunton locals reportedly watched him standing under a pear tree, speaking at length with the governor as he sat in his carriage. (I don’t know of any time the governor actually visited that town.) In 1815 John Adams put his own spin on the younger man’s progress:

So Adams and friends came up with a plan.

TOMORROW: An old rival returns.

After graduating, Leonard earned his master’s degree and then went into the law. He was a leader among other bright young attorneys like Josiah Quincy, Jr., Francis Dana, and John Trumbull.

In 1767 Leonard married Sarah White, daughter of his legal mentor. Her other suitors had included Robert Treat Paine. Sarah Leonard died young, however, and in 1770 Leonard remarried to Sarah Hamock, daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant, in Trinity Church.

Inheriting his first father-in-law’s legal practice and his second father-in-law’s money, Leonard settled in Taunton. He quickly gained a royal appointment as the King’s Attorney for Bristol County and a seat in the Massachusetts General Court.

In that legislature Leonard worked with the province’s most fervent Whigs. He was on the committee of correspondence and a committee that called for the removal of Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and Chief Justice Peter Oliver.

Around the time of the Boston Tea Party, however, Leonard moved toward the side of the royal government. He said he’d come to distrust the motives of men like Samuel Adams. In February 1774 Leonard voted against impeaching Oliver.

People said Gov. Hutchinson had lured Leonard over to the Crown. Taunton locals reportedly watched him standing under a pear tree, speaking at length with the governor as he sat in his carriage. (I don’t know of any time the governor actually visited that town.) In 1815 John Adams put his own spin on the younger man’s progress:

As a Member of the House of Representatives, even down to the year 1770 he made the most ardent Speeches which were delivered in that House against Great Britain and in favour of the Colonies. His Popularity became allarming. The two Sagacious Spirits Hutchinson and [Jonathan] Sewall Soon penetrated his Character of which indeed he had exhibited very visible proofs.Whatever had motivated Daniel Leonard’s political shift, in June 1774 he still had enough of a history of standing up to the royal governors that several colleagues recommended him for the assembly’s committee to respond to the Boston Port Act. But Whig leaders didn’t trust him. He would, they suspected, tell Gov. Thomas Gage everything that committee was talking about.

He had married a daughter of Mr Hammock, who had left her a Portion, as it was thought in that day. He wore a broad Gold Lace round the rim of his Hatt. He had made his Cloak glitter with laces Still broader. He had sett up his Charriot and Pair and constantly travelled in it from Taunton to Boston. This made the World Stare. It was a Novelty. Not another Lawyer in the Province, Attorney or Barrister, of whatever Age Reputation Rank or Station presumed to ride in a Coach or a Charriot.

The discerning ones Soon perceived that Wealth and Power must have charms to a heart that delighted in So much finery and indulged in such unusual Expence. Such Marks could not escape the vigilant Eyes of the two Arch Tempters Hutchinson and Sewall, who had more Art, Insinuation and Adress than all the rest of their Party.

Poor Daniel was beset, with great Zeal for his Conversion. Hutchinson sent for him, courted him with the Ardor of a Lover, reasoned with him flattered him, overawed him frightened him, invited him to come frequently to his House.

As I was Intimate with Mr Leonard during the whole of this process I had the Substance of this Information from his own Mouth, was a Witness to the progress of the Impression made upon him, and to many of the Labours and Struggles of his Mind between his Interest or his Vanity and his Duty.

So Adams and friends came up with a plan.

TOMORROW: An old rival returns.

Saturday, June 22, 2024

The Sestercentennial of Salem as the Seat of Government

Gov. Thomas Hutchinson prorogued the Massachusetts General Court on 8 Mar 1774, stating:

Two months later, Gen. Thomas Gage arrived as the new governor, and the legislature didn’t have Thomas Hutchinson to kick around anymore.

A newly elected General Court convened in Boston on 25 May. By the end of the day, the legislatures had elected twenty-eight gentlemen to sit on the new Council.

The next morning, Gov. Gage vetoed thirteen of those men. So things were off to a smooth start.

The House started to address the petitions, bills, and other business before it. On Saturday, 28 May, the governor sent a message that he was adjourning the legislature, and the term would start up again on 7 June in the courthouse at Salem (shown above).

That action was part of the British government’s policy of isolating and punishing Boston until the town repaid the cost of the tea destroyed the previous December. Gage acted on instructions from London. Deciding when and where the legislature would meet had long been a Massachusetts governor’s power.

Naturally, the House’s first business when it reconvened was to complain about having to be in Salem. Its resolution argued that since Gage had acted “unnecessarily, or merely in Obedience to an Instruction, and without exercising that Judgment and Discretion of his own,” he wasn’t properly exercising the governor’s prerogative.

A day after that, the House members responded to Gage’s speech opening the session with more complaints about being in Salem.

Late on the morning of 9 June, the House made itself “a Committee to consider the State of the Province” after the Boston Port Bill. After some private and unrecorded debate, the lawmakers appointed a committee to recommend responses to that situation. Its members were:

That committee thus included three of Boston’s four representatives to the General Court. The remaining member was John Hancock, who’s not mentioned in the record of the Salem session, suggesting he wasn’t even there.

Paine later wrote that eight of those men “were considered as firm in the Opposition to British measures.” The exception?

I have passed over without notice the groundless, unkind, and illiberal charges and insinuations made by each of the other branches against the Governor…So those insinuations didn’t bother him, not at all.

Two months later, Gen. Thomas Gage arrived as the new governor, and the legislature didn’t have Thomas Hutchinson to kick around anymore.

A newly elected General Court convened in Boston on 25 May. By the end of the day, the legislatures had elected twenty-eight gentlemen to sit on the new Council.

The next morning, Gov. Gage vetoed thirteen of those men. So things were off to a smooth start.

The House started to address the petitions, bills, and other business before it. On Saturday, 28 May, the governor sent a message that he was adjourning the legislature, and the term would start up again on 7 June in the courthouse at Salem (shown above).

That action was part of the British government’s policy of isolating and punishing Boston until the town repaid the cost of the tea destroyed the previous December. Gage acted on instructions from London. Deciding when and where the legislature would meet had long been a Massachusetts governor’s power.

Naturally, the House’s first business when it reconvened was to complain about having to be in Salem. Its resolution argued that since Gage had acted “unnecessarily, or merely in Obedience to an Instruction, and without exercising that Judgment and Discretion of his own,” he wasn’t properly exercising the governor’s prerogative.

A day after that, the House members responded to Gage’s speech opening the session with more complaints about being in Salem.

Late on the morning of 9 June, the House made itself “a Committee to consider the State of the Province” after the Boston Port Bill. After some private and unrecorded debate, the lawmakers appointed a committee to recommend responses to that situation. Its members were:

- speaker Thomas Cushing

- Joseph Hawley

- clerk Samuel Adams

- William Phillips

- Robert Treat Paine

- James Warren

- John Tyng

- Daniel Leonard

- Timothy Pickering

That committee thus included three of Boston’s four representatives to the General Court. The remaining member was John Hancock, who’s not mentioned in the record of the Salem session, suggesting he wasn’t even there.

Paine later wrote that eight of those men “were considered as firm in the Opposition to British measures.” The exception?

by the mixture of nominations from both parties in the House the Name of Daniel Leonard was so repeated, that the Speaker found himself Obliged to nominate him & he was chosen.TOMORROW: Who was Daniel Leonard?

Friday, June 21, 2024

“He would not consent to any alteration in the style”

Among the many disputes between Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and the Massachusetts General Court was one over how new laws were designated by year.

According to Hutchinson, the usual form for Parliament’s laws, copied by the colonial legislature, was “Anno Regni Regis Georgii Magnæ Britannia Franciæ &c.”—in the [number] year of George [number], King of Great Britain, France, and so on. (British monarchs continued to claim France until the Treaty of Amiens in 1802.)

In the spring of 1773, House clerk Samuel Adams started using the English phrase “In the thirteenth year of King George the third,” a common legal formula.

Hutchinson didn’t like that. He considered Adams “a Member of the House who does nothing without design.” (Though he added, “The House in general I suppose were not acquainted with the design.”)

On 28 June, the governor wrote to the assembly: “I am not only averse to Innovations, unless a manifest Reason can be given, but I am also restrained by my Instructions from consenting to any Bill of an unusual and extraordinary Nature without a suspending Clause.” He asked the legislature to return to the old style.

The Massachusetts House of course named a committee to respond, and of course the first member on that committee was Samuel Adams. The reply (hand-delivered by others) was:

Writing to the Lords of Trade in August, Hutchinson insisted: “the English words did not convey the same ideas and the alteration was proposed to the House meerly to get rid of Magne Britannæ or any words which imply it.”

That General Court had a second term from 26 January to 9 March, with the impeachment of Chief Justice Peter Oliver one of the main pieces of business—creating another big dispute with the governor.

In that session, Hutchinson noticed that the House used “Anno Regni Regis Georgii” but “left out the words et cætera.” He declared he now wouldn’t approve any bill unless it contained the whole phrase “Magnæ Britanniæ Franciæ & Hiberniæ.”

In a volume of history Hutchinson wrote a few years later, he connected those small edits to a big plan for elevating the province of Massachusetts to the same level as Britain:

Gov. Hutchinson felt that he was standing up for the British constitution by insisting that George III be designated king of Great Britain, France, and Ireland—leaving no possibility that he was separately king of Massachusetts, or that the colonies might be listed at the same level as those core parts of the empire.

At the same time, Hutchinson was sure this nuance would be lost on most people in Massachusetts. They would assume his insistence on traditional wording arose “from mere humour” or peevishness. “To this inconvenience he was,” Hutchinson wrote of himself, “in many instances, forced to submit, to avoid a greater, by the controversy in which his attempting an explanation would involve him, which, in every answer, would bring fresh abuse.”

According to Hutchinson, the usual form for Parliament’s laws, copied by the colonial legislature, was “Anno Regni Regis Georgii Magnæ Britannia Franciæ &c.”—in the [number] year of George [number], King of Great Britain, France, and so on. (British monarchs continued to claim France until the Treaty of Amiens in 1802.)

In the spring of 1773, House clerk Samuel Adams started using the English phrase “In the thirteenth year of King George the third,” a common legal formula.

Hutchinson didn’t like that. He considered Adams “a Member of the House who does nothing without design.” (Though he added, “The House in general I suppose were not acquainted with the design.”)

On 28 June, the governor wrote to the assembly: “I am not only averse to Innovations, unless a manifest Reason can be given, but I am also restrained by my Instructions from consenting to any Bill of an unusual and extraordinary Nature without a suspending Clause.” He asked the legislature to return to the old style.

The Massachusetts House of course named a committee to respond, and of course the first member on that committee was Samuel Adams. The reply (hand-delivered by others) was:

The House have read your Message just now laid before them, and cannot but wonder that you should consider the Bills that have passed the two Houses as of an extraordinary nature, merely because the words expressive of the Year of the King’s Reign are in plain English instead of the Roman Language as usual; or that your Excellency should think yourself restrained by an Instruction from consenting to them.Nonetheless, the House said it would revert to the previous phrasing.

Writing to the Lords of Trade in August, Hutchinson insisted: “the English words did not convey the same ideas and the alteration was proposed to the House meerly to get rid of Magne Britannæ or any words which imply it.”

That General Court had a second term from 26 January to 9 March, with the impeachment of Chief Justice Peter Oliver one of the main pieces of business—creating another big dispute with the governor.

In that session, Hutchinson noticed that the House used “Anno Regni Regis Georgii” but “left out the words et cætera.” He declared he now wouldn’t approve any bill unless it contained the whole phrase “Magnæ Britanniæ Franciæ & Hiberniæ.”

In a volume of history Hutchinson wrote a few years later, he connected those small edits to a big plan for elevating the province of Massachusetts to the same level as Britain:

Mr. Adams’s attention to the cause in which he was engaged would not suffer him to neglect even small circumstances, which could be made subservient to it. From this attention, in four or five years, a great change had been made in the language of the general assembly. That which used to be called the “court house,” or “town house,” had acquired the name of the “state house;” “the house of representatives of Massachusetts Bay,” had assumed the name of “his majesty’s commons;”—the “debates of the assembly,” are styled “parliamentary debates;”—“acts of parliament,” “acts of the British parliament;”—“the province laws,” “the laws of the land;”—“the charter,” a grant from royal grace or favour, is styled the “compact;”—and now “impeach” is used for “complain,” and the “house of representatives” are made analogous to the “commons,” and the “council” to the “lords,” to decide in cases of high crimes and misdemeanours, and, upon the same reason, in cases of high treason.In a small way, those linguistic changes did get to the crux of Massachusetts’s dispute with the Crown. Did the Parliament in London have authority over every colony within the empire? Or was a colony’s own legislature the only parliament that could levy taxes and make laws for its people?

Gov. Hutchinson felt that he was standing up for the British constitution by insisting that George III be designated king of Great Britain, France, and Ireland—leaving no possibility that he was separately king of Massachusetts, or that the colonies might be listed at the same level as those core parts of the empire.

At the same time, Hutchinson was sure this nuance would be lost on most people in Massachusetts. They would assume his insistence on traditional wording arose “from mere humour” or peevishness. “To this inconvenience he was,” Hutchinson wrote of himself, “in many instances, forced to submit, to avoid a greater, by the controversy in which his attempting an explanation would involve him, which, in every answer, would bring fresh abuse.”

Thursday, June 20, 2024

“Beyond the Thirteen” at History Camp Boston, 10 Aug.

History Camp Boston will take place on Saturday, 10 August, with ancillary events before and after.

At organizer Lee Wright’s request, I’ll speak on the topic “Beyond the Thirteen: The American Colonies That Stayed with Britain”:

There are more than fifty other sessions on the History Camp Boston schedule, including a whole lot about the Revolution and eighteenth-century America:

This main session of History Camp Boston will once again take place in the Suffolk University Law School building, 120 Tremont Street. Doors will open at 8:00 A.M., and the presentations are scheduled to start at 9:00. That gathering will end at 5:30 P.M., but folks can choose to attend Revolution’s Edge at the Old North Church an hour later.

On Sunday, 11 August, there are four tours available at extra cost—two inside Boston, one on the North Shore, and one on the South Shore (which is already sold out).

Registration for the Saturday sessions with breakfast refreshments and lunch costs $110. A T-shirt, a Sunday tour, and a donation that brings an invitation to a reception on Friday night are all extra. For all the details, start on this page.

At organizer Lee Wright’s request, I’ll speak on the topic “Beyond the Thirteen: The American Colonies That Stayed with Britain”:

As Americans we speak of “the thirteen colonies,” but that includes only those colonies that rebelled in 1775. Britain’s empire in the western hemisphere included up to three dozen more colonies, depending on how one counts. Some were small islands while others were older, larger, and wealthier than the colonies that sent delegates to the Continental Congress. Most of those places were subject to the same new taxes that caused such problems along the north Atlantic coast. This talk will map the full boundaries of the British Empire in 1775, look at the Congress’s fraught relations with those other colonies, and explore why they didn’t join the move toward independence.That’s a different sort of topic for me—broader, longer, and without an obvious narrative. But I’m plucking smaller stories out of the records.

There are more than fifty other sessions on the History Camp Boston schedule, including a whole lot about the Revolution and eighteenth-century America:

- 1774: The Year the Revolution Began, Robert J. Allison

- An American Revolution Christmas Night: Washington Crossing, Salina B. Baker

- The Debatable Lands: The History of Georgia 1733–1750, Wheeler Bryan, Jr.

- From Daughters of Liberty to Republican Mothers: How Women Evolved From the Eve of the Revolution to the Foundations of the Early Republic, Melissa Bryson

- The Chocolate Girl and Drinking Chocolate in the 18th Century, Patricia A. Buttaro

- Civilians Trapped Behind the Lines During the Siege of Boston, Alexander R. Cain

- Mercy Otis Warren and the Writings of a Revolutionary: American Calliope, Michele Gabrielson

- General Washington’s Spymaster: Major Benjamin Tallmadge, Sam Garrity

- The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 and the Boston Tea Party, Chris Hall

- They Tore Down the King’s Colours (on the storming of Fort William & Mary), Cynthia Hatch

- Pups of Liberty: Animating the Revolution, Jennifer C. and Bert Klein

- How American Rebels Blocked British Control of the Hudson River: Iron in the Water, Kiersten Marcil

- Slavery’s Legacy in a New England Town, Elizabeth Matelski and Abby Battis

- Captain Slarrow, Major Montague, and the 1774 North Leverett Sawmill, Will Melton

- Researching Revolutionary War Patriots: The Challenge, the Results, and Tips Based on Our Project in Hingham, Ellen Stine Miller and Susan Garret Wetzel

- What’s New at 250?: Interpreting the Revolution for Today’s Audiences, Jake Sconyers and Nikki Stewart

- The British Are Here, Richard O. Tucker

This main session of History Camp Boston will once again take place in the Suffolk University Law School building, 120 Tremont Street. Doors will open at 8:00 A.M., and the presentations are scheduled to start at 9:00. That gathering will end at 5:30 P.M., but folks can choose to attend Revolution’s Edge at the Old North Church an hour later.

On Sunday, 11 August, there are four tours available at extra cost—two inside Boston, one on the North Shore, and one on the South Shore (which is already sold out).

Registration for the Saturday sessions with breakfast refreshments and lunch costs $110. A T-shirt, a Sunday tour, and a donation that brings an invitation to a reception on Friday night are all extra. For all the details, start on this page.

Wednesday, June 19, 2024

John Linzee and “the appearance of mental derangement”

On 4 Oct 1792, about two months after giving birth to her tenth child in Boston, Susannah Linzee died. She was thirty-eight years old.

That baby, named George Inman Linzee, died the following 21 March.

His next oldest sister, Mary Inman Linzee, died on 18 May.

Within a year, retired Royal Navy captain John Linzee had lost his wife and their two youngest children. He was still responsible for six older children.

(The oldest, Samuel Hood Linzee, was by then a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. He had gotten a head start in the seniority system by being listed as his father’s servant and senior clerk aboard H.M.S. Falcon in 1775, when he was less than two years old.)

The death of Linzee’s wife also led to him losing his house on Essex Street in Boston. The merchant John Rowe had left it to his niece Susannah in his will, but only after the death of his widow, Hannah Rowe.

Rowe had her own house nearby, but she decided to reclaim this one now that Susannah hadn’t survived to inherit it. In July 1794 the widow told the court she owned the

John William Linzee’s 1917 history of the family reprints a couple of documents from that court case but doesn’t show how it was resolved. He declared, “this disagreement was of short duration,” pointing to how Hannah Rowe left bequests to the Linzee children. However, that will was written in 1803, after John Linzee had died. It would be just as consistent with Hannah Rowe strong-arming him out of the scene and raising her great-nephews and great-nieces herself.

In fact, there’s evidence that the death of his wife cast Linzee into a depression that alienated him from people. The merchant Samuel Breck, who praised the captain as “a good officer” in earlier years, recalled:

The Linzees’ oldest daughter, Hannah, married Thomas C. Amory. Their son John Inman Linzee served as treasurer of Massachusetts. A granddaughter married a grandson of Dr. John Warren, a great-granddaughter married a grandson of Paul Revere, and, as I wrote here, another granddaughter married a grandson of William Prescott.

That baby, named George Inman Linzee, died the following 21 March.

His next oldest sister, Mary Inman Linzee, died on 18 May.

Within a year, retired Royal Navy captain John Linzee had lost his wife and their two youngest children. He was still responsible for six older children.

(The oldest, Samuel Hood Linzee, was by then a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. He had gotten a head start in the seniority system by being listed as his father’s servant and senior clerk aboard H.M.S. Falcon in 1775, when he was less than two years old.)

The death of Linzee’s wife also led to him losing his house on Essex Street in Boston. The merchant John Rowe had left it to his niece Susannah in his will, but only after the death of his widow, Hannah Rowe.

Rowe had her own house nearby, but she decided to reclaim this one now that Susannah hadn’t survived to inherit it. In July 1794 the widow told the court she owned the

House & Land…demised to the said John Linzee for a Term that is past, after which it ought to return to her again, but the said John Linzee still withholds the said House & Land & their appurtenancesShe sued the retired captain for £1,000. Sheriff Jeremiah Allen certified that he had “attached a chair as the property of the within named John Linzee and left a summons at his last and usual place of Abode.”

John William Linzee’s 1917 history of the family reprints a couple of documents from that court case but doesn’t show how it was resolved. He declared, “this disagreement was of short duration,” pointing to how Hannah Rowe left bequests to the Linzee children. However, that will was written in 1803, after John Linzee had died. It would be just as consistent with Hannah Rowe strong-arming him out of the scene and raising her great-nephews and great-nieces herself.

In fact, there’s evidence that the death of his wife cast Linzee into a depression that alienated him from people. The merchant Samuel Breck, who praised the captain as “a good officer” in earlier years, recalled:

At her death the eccentricities of the captain assumed the appearance of mental derangement. He retired to a small box in the neighborhood of Milton, where he lived entirely by himself, rode out armed, and tapped his cider-cask by firing a ball into the head.Linzee died in 1798. He left his estate, worth almost $18,000, to his children and grandchildren and asked to be buried next to his wife.

As he was seldom to be seen at home, he fixed a parcel of hooks in his kitchen for the butchers to hang their meat on, giving a standing order to put daily a joint upon one of the hooks. It so happened on one occasion, when he was detained in Boston about a fortnight by sickness, that he found on his return home fifteen or sixteen pieces of meat hanging around the walls of his kitchen.

The Linzees’ oldest daughter, Hannah, married Thomas C. Amory. Their son John Inman Linzee served as treasurer of Massachusetts. A granddaughter married a grandson of Dr. John Warren, a great-granddaughter married a grandson of Paul Revere, and, as I wrote here, another granddaughter married a grandson of William Prescott.

Tuesday, June 18, 2024

“Delivered to said linzee two hundred and seven sheep”

In January 1791, Capt. John Linzee, R.N., wrote that in the following month he planned to make his second return to Boston since the end of the American War.

As I described yesterday, Linzee’s wife, the former Susannah Inman, had settled in that port with most of their children in a house left to her by the merchant John Rowe.

According to Royal Navy records, John Linzee resigned from the service in September 1791. (Other sources say he retired after events of the following year, but this looks more authoritative.)

The captain settled in Boston, and Susannah Inman gave birth to a son on 7 Aug 1792.

After that, John Linzee went through a string of hardships.

First, on 30 August, Joseph Tucker of Dartmouth sued the captain for the cost of sheep he had collected back on 1 May 1775. In September, Suffolk County sheriff Jeremiah Allen reported arresting Linzee on a writ, though he let the man go on bail.

At first Linzee argued that he had been and remained “a Subject of the King of Great Britain and not a Citizen of this Commonwealth,” so the case should be handled in the federal system. The Barnstable County court refused.

Ebenezer Meiggs of Rochester provided the most coherent description of the dispute:

Back on 31 May 1775, islander Elisha Nye had lodged a similar complaint against Capt. Linzee for taking sheep and calves off “one of the Elizabeth Islands, commonly called Naushan [Nashawena].” Like Tucker, Nye felt that he and Linzee had agreed on terms, only for the navy to grab livestock and sail away. That complaint went to the Massachusetts committee of safety and then into a file, and it doesn’t appear to have come up during Tucker v. Linzee.

Undoubtedly in May 1775 Capt. Linzee was acting on behalf of the Crown. His assignment was to collect food for the besieged Boston garrison. By coming to live in Massachusetts with his wife and children, however, the retired captain had made himself vulnerable to a personal lawsuit.

In May 1793, a Barnstable County jury found against Linzee and ordered him to pay Tucker £150 and costs.

According to family historian John William Linzee, “the debt was paid by Captain Linzee out of his own private purse, and there is no evidence that he was ever reimbursed by the English government.” Neither is there documentation in that history of Linzee’s payment, however.

But by 1793 that court case was the least of the captain’s troubles.

TOMORROW: Deaths in the family.

As I described yesterday, Linzee’s wife, the former Susannah Inman, had settled in that port with most of their children in a house left to her by the merchant John Rowe.

According to Royal Navy records, John Linzee resigned from the service in September 1791. (Other sources say he retired after events of the following year, but this looks more authoritative.)

The captain settled in Boston, and Susannah Inman gave birth to a son on 7 Aug 1792.

After that, John Linzee went through a string of hardships.

First, on 30 August, Joseph Tucker of Dartmouth sued the captain for the cost of sheep he had collected back on 1 May 1775. In September, Suffolk County sheriff Jeremiah Allen reported arresting Linzee on a writ, though he let the man go on bail.

At first Linzee argued that he had been and remained “a Subject of the King of Great Britain and not a Citizen of this Commonwealth,” so the case should be handled in the federal system. The Barnstable County court refused.

Ebenezer Meiggs of Rochester provided the most coherent description of the dispute:

I being at one of the Elizabeth Islands Called Peek [Penikese? Pasque?] in Company with Joseph tucker of Dartmouth I heard one John Linzee a Captain of a brittish ship of war bargain with said tucker for two hundred and seven sheep for which he agreed to give two dollars for Each sheep besides or without the woolLinzee denied ever having made such a deal.

accordingly the said tucker delivered to said linzee two hundred and seven sheep on board his ship and as the said Linzee was in a hurry to gett them a board he ordered them to be got aboard before they ware all Shorn Promissing said tucker that he would take his shearers on board the ship next morning and that they might take the wool of them or he would Pay the value of it

accordingly the sheep ware Put on board with the wool on as many as one hundred and I helped get them on board but the next morning the said Linzee hove up and went off without fetching the Shearers on board or Paying for the sheep

Back on 31 May 1775, islander Elisha Nye had lodged a similar complaint against Capt. Linzee for taking sheep and calves off “one of the Elizabeth Islands, commonly called Naushan [Nashawena].” Like Tucker, Nye felt that he and Linzee had agreed on terms, only for the navy to grab livestock and sail away. That complaint went to the Massachusetts committee of safety and then into a file, and it doesn’t appear to have come up during Tucker v. Linzee.

Undoubtedly in May 1775 Capt. Linzee was acting on behalf of the Crown. His assignment was to collect food for the besieged Boston garrison. By coming to live in Massachusetts with his wife and children, however, the retired captain had made himself vulnerable to a personal lawsuit.

In May 1793, a Barnstable County jury found against Linzee and ordered him to pay Tucker £150 and costs.

According to family historian John William Linzee, “the debt was paid by Captain Linzee out of his own private purse, and there is no evidence that he was ever reimbursed by the English government.” Neither is there documentation in that history of Linzee’s payment, however.

But by 1793 that court case was the least of the captain’s troubles.

TOMORROW: Deaths in the family.

Monday, June 17, 2024

Capt. John Linzee’s Ties to Boston

This is the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775.

Among the Massachusetts Historical Society’s unique artifacts from that event are the crossed swords of Col. William Prescott from the provincial troops and Capt. John Linzee from the Royal Navy, as highlighted here.

Those weapons were donated by the historian William Hickling Prescott, his wife Susannah, and her cousin. William was a grandson of the colonel. Susannah was a granddaughter of the captain.

Though born in England and serving the king, Capt. Linzee had strong ties to Boston. In 1772, while master of H.M.S. Beaver, he married Susannah Inman of Cambridge, favored niece of John and Hannah Rowe.

The Linzees started having children. The first was born in Plymouth, England; the second back in Boston during the siege; the third on the Delaware River, reportedly during a battle which it didn’t outlive.

The Linzees’ fourth child was born at Barbados, the next four in Plymouth. The captain had a busy war.

Susannah Linzee’s father, Ralph Inman, had left Boston in the evacuation of 1776. Her stepmother, Elizabeth (Murray Campbell Smith) Inman, never left. She kept hold of their property, which is how he could return to his Cambridge estate when the fighting died down.

John Rowe also never left. When that merchant died in 1787, he bequeathed Susannah Linzee some Boston property. She came back to America, and the Linzees’ ninth child was born in Boston in 1789.

The following September, Capt. Linzee sailed H.M.S. Penelope into Boston harbor, writing to Gov. John Hancock that he intended to salute the flag of the U.S. of A. with thirteen guns if the battery at the Castle would reciprocate.

Linzee’s letter also mentioned his “exceeding ill State of Health,” and indeed he was so sick the Penelope sailed away without him while he recuperated in his wife’s house. A few months later, however, Capt. Linzee was back “in perfect health” on his ship along with his two eldest sons.

In the following years, things started to go wrong for Capt. Linzee.

TOMORROW: A British officer in Boston.

Among the Massachusetts Historical Society’s unique artifacts from that event are the crossed swords of Col. William Prescott from the provincial troops and Capt. John Linzee from the Royal Navy, as highlighted here.

Those weapons were donated by the historian William Hickling Prescott, his wife Susannah, and her cousin. William was a grandson of the colonel. Susannah was a granddaughter of the captain.

Though born in England and serving the king, Capt. Linzee had strong ties to Boston. In 1772, while master of H.M.S. Beaver, he married Susannah Inman of Cambridge, favored niece of John and Hannah Rowe.

The Linzees started having children. The first was born in Plymouth, England; the second back in Boston during the siege; the third on the Delaware River, reportedly during a battle which it didn’t outlive.

The Linzees’ fourth child was born at Barbados, the next four in Plymouth. The captain had a busy war.

Susannah Linzee’s father, Ralph Inman, had left Boston in the evacuation of 1776. Her stepmother, Elizabeth (Murray Campbell Smith) Inman, never left. She kept hold of their property, which is how he could return to his Cambridge estate when the fighting died down.

John Rowe also never left. When that merchant died in 1787, he bequeathed Susannah Linzee some Boston property. She came back to America, and the Linzees’ ninth child was born in Boston in 1789.

The following September, Capt. Linzee sailed H.M.S. Penelope into Boston harbor, writing to Gov. John Hancock that he intended to salute the flag of the U.S. of A. with thirteen guns if the battery at the Castle would reciprocate.

Linzee’s letter also mentioned his “exceeding ill State of Health,” and indeed he was so sick the Penelope sailed away without him while he recuperated in his wife’s house. A few months later, however, Capt. Linzee was back “in perfect health” on his ship along with his two eldest sons.

In the following years, things started to go wrong for Capt. Linzee.

TOMORROW: A British officer in Boston.

Sunday, June 16, 2024

“A novel twist to this well-trod approach”

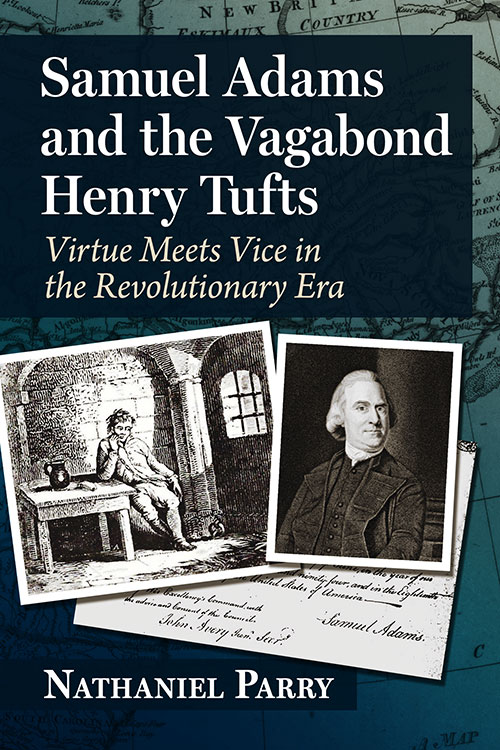

Later this month McFarland is due to publish Nathaniel Parry’s Samuel Adams and the Vagabond Henry Tufts: Virtue Meets Vice in the Revolutionary Era.

Author Gene Procknow has shared his thorough early review:

While Adams was devoted to political action, for example, Tufts joined the Continental Army only for the enlistment bonus and then promptly deserted. He was a habitual criminal, though Parry “asserts that if he were a tea smuggler rather than a thief, Tufts would be lauded as a Revolutionary hero.” Tufts did get a certain amount of glory as a rogue from his 1807 autobiography, most likely ghostwritten, which is the main source on his life.

The similarities between the two men can also be telling in reflecting attitudes that permeated their society. Procknow highlights how they shared common sentiments about slavery and race. Even after spending years with the Abenaki, Tufts (or at least his book) refers to Native Americans as “savages,” a term Adams also used.

At times, the review says, Parry pushes too hard on its theme of socioeconomic difference:

Author Gene Procknow has shared his thorough early review:

Comparative founder profiles are a crowded book genre with numerous volumes depicting any combination of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin as rivals, friends, or brothers. Nathaniel Parry offers a novel twist to this well-trod approach by comparing the lives of a famous founder, Samuel Adams, with a common criminal, Henry Tufts. . . .While most of those dual biographies could trace a long relationship between their subjects, in this book the insights arise from the big gap between the two men.

Their lives briefly intersected in 1794 when Massachusetts Governor Adams saved Tufts’ life by commuting the thief’s death sentence to life in prison.

While Adams was devoted to political action, for example, Tufts joined the Continental Army only for the enlistment bonus and then promptly deserted. He was a habitual criminal, though Parry “asserts that if he were a tea smuggler rather than a thief, Tufts would be lauded as a Revolutionary hero.” Tufts did get a certain amount of glory as a rogue from his 1807 autobiography, most likely ghostwritten, which is the main source on his life.

The similarities between the two men can also be telling in reflecting attitudes that permeated their society. Procknow highlights how they shared common sentiments about slavery and race. Even after spending years with the Abenaki, Tufts (or at least his book) refers to Native Americans as “savages,” a term Adams also used.

At times, the review says, Parry pushes too hard on its theme of socioeconomic difference:

For example, the author overplays class conflict by asserting that Continental Army officers were “motivated more by class advancement than by deeply held convictions for the revolution” and, as evidence, cites a lieutenant who fought at Bunker Hill and Benedict Arnold’s self-aggrandizement (142, 241). However, for the vast majority in the Continental Army, officer advancement did not lead to newly found post-war wealth or status. . . .In all, Procknow concludes, by “innovatively comparing the lives of Samuel Adams and Henry Tufts,” Parry does a good job showing how “the nation’s founding was the product of elites and ordinary people” both.

Other minor weaknesses include several technical misstatements such as mislabeling Congressional members (Roger Sherman represented Connecticut, not Massachusetts), the object of British troops on the Lexington and Concord raid (General Thomas Gage sought four missing cannons and not the capture of Samuel Adams and John Hancock) and the number of allowable lashes in the Continental Army (100 was the maximum, not 500).

Saturday, June 15, 2024

Preview of “The Promise of Liberty” in Charlestown

From now till Monday, coinciding with the battle anniversary, the Bunker Hill Museum is playing host to a pop-up exhibit of historic documents showing the expansion of American constitutional freedom, organized by Seth Kaller.

Pictured above are:

This is a prototype of a larger traveling exhibit (or series of exhibits) that Kaller envisions called The Promise of Liberty. Its website explains:

Pictured above are:

- 18 July 1776 New-England Chronicle printing of the Declaration of Independence.

- Newspaper printing of the proposed new U.S. Constitution, followed by George Washington’s letter to the Congress as convention chairman explaining the benefits of the new government framework.

- Newspaper reporting the first twelve proposed amendments to that constitution.

- Statement autographed by Frederick Douglass.

- Newspaper report on Abraham Lincoln’s speech in Independence Hall on his way to Washington, D.C., in 1861.

- Poster from 1913 showing the progress of woman suffrage.

- Prepared text of Martin Luther King’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial, to which he improvised the “Dream” passage.

This is a prototype of a larger traveling exhibit (or series of exhibits) that Kaller envisions called The Promise of Liberty. Its website explains:

The Exhibit aims to inspire a sense of unity and pride that cuts across political divides, while encouraging gratitude for the liberties we have and igniting a collective determination to defend and expand upon the liberties promised 250 years ago.The organization is now talking to potential sponsors, partners, and hosts in the Sestercentennial years. In the meantime, folks can get a preview in Charlestown this weekend.

Friday, June 14, 2024

McConville on the Quebec Act at 250, 27 June

Years back, I decided to look into the burning question of whether the Quebec Act of 1774 was one of what American Patriots called the “Intolerable Acts.”

That law wasn’t, after all, directed at Massachusetts, even if the Suffolk Resolves treated the acceptance of Roman Catholicism in a population hundreds of miles away as a serious affront and threat.

The result was discovering that the American Patriots of 1774 didn’t call anything the “Intolerable Acts.” As I wrote in this article, that label surfaced in U.S. history textbooks in the late nineteenth century and was then retroactively embedded in the past.

Nonetheless, the Quebec Act was one of the significant pieces of legislation to come out of Lord North’s government. Years in the making, that law incorporated a large formerly French territory into the British Empire. His Majesty’s government accepted the civil code and religion established under the former regime. The law even expanded the province to include the lands between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

On 27 June, the Congregational Library and Archives will host “The Quebec Act at 250,” an online discussion with Prof. Brendan McConville exploring the significance of how the francophone province was folded into the British North American colonies—and why it made Congregationalists so profoundly uncomfortable.

McConville is Professor of History at Boston University and Director of the David Center for the American Revolution at the American Philosophical Society. He’s the author of These Daring Disturbers of the Public Peace, The King’s Three Faces: The Rise and Fall of Royal America, 1688-1776, and The Brethren: A Story of Faith and Conspiracy in Revolutionary America. He’s always offering provocative ways to look at the American Revolution.

This online event is scheduled to start at 1:00 P.M. It is free. To register and receive the link for that session, go to this page.

That law wasn’t, after all, directed at Massachusetts, even if the Suffolk Resolves treated the acceptance of Roman Catholicism in a population hundreds of miles away as a serious affront and threat.

The result was discovering that the American Patriots of 1774 didn’t call anything the “Intolerable Acts.” As I wrote in this article, that label surfaced in U.S. history textbooks in the late nineteenth century and was then retroactively embedded in the past.

Nonetheless, the Quebec Act was one of the significant pieces of legislation to come out of Lord North’s government. Years in the making, that law incorporated a large formerly French territory into the British Empire. His Majesty’s government accepted the civil code and religion established under the former regime. The law even expanded the province to include the lands between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

On 27 June, the Congregational Library and Archives will host “The Quebec Act at 250,” an online discussion with Prof. Brendan McConville exploring the significance of how the francophone province was folded into the British North American colonies—and why it made Congregationalists so profoundly uncomfortable.

McConville is Professor of History at Boston University and Director of the David Center for the American Revolution at the American Philosophical Society. He’s the author of These Daring Disturbers of the Public Peace, The King’s Three Faces: The Rise and Fall of Royal America, 1688-1776, and The Brethren: A Story of Faith and Conspiracy in Revolutionary America. He’s always offering provocative ways to look at the American Revolution.

This online event is scheduled to start at 1:00 P.M. It is free. To register and receive the link for that session, go to this page.

Thursday, June 13, 2024

The Long Year of 1774 with Emerging Revolutionary War

I started this week by talking about the momentous events of 1774 in New England with Rob Orrison of the Emerging Revolutionary War group.

You can find the video recording by clicking on the image above and here on YouTube. Though Zoom calls like this usually make better podcasts than visual entertainment.

You can find the video recording by clicking on the image above and here on YouTube. Though Zoom calls like this usually make better podcasts than visual entertainment.

Wednesday, June 12, 2024

Tea with Gen. Gage in Salem This Week

In June 1774, 250 years ago, Salem suddenly became more important.

Parliament’s Boston Port Bill took effect on 1 June, and the harbor of Salem and Marblehead became Massachusetts’s largest port open to trade from outside the colony. The Customs office moved there.

Also, Gov. Thomas Gage adjourned the Massachusetts General Court from Boston to Salem, following orders from London. That move didn’t require a new law since the royal governor already had the power to convene the legislature where he chose. That didn’t stop most of the new session being taken up with complaints about being in Salem.

When Gage moved to the region, renting a house in nearby Danvers, he also brought a contingent of British soldiers. There doesn’t appear to have been as much friction between those troops and the locals as in Boston in 1768–1770, but the town governments still raised concerns.

This week the city’s historical organizations are commemorating that period with some public events.

Thursday, 13 June, 7:00 P.M.

Tea’s Party: From Boston to Salem and Back Again

Salem Armory Regional Visitor Center

James R. Fichter speaks about how, despite the so-called Boston Tea Party of 1773, large shipments of tea from the East India Company were sold in North America. The survival of the Boston tea shaped Massachusetts politics in 1774, impeded efforts to reimburse the company for its losses, and hinted at the enduring conflict between consumer demand and political boycotts.

That tension was not confined to Boston. As Gen. Gage and the colonial government relocated to Salem in the summer of 1774, Essex County residents found committing to a boycott just as difficult as Bostonians had.

Fichter is Associate Professor in Global and Area Studies at the University of Hong Kong. He is the author of So Great a Profit: How the East Indies Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism and Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773–1776.

This event is free. For directions, visit this page.

Saturday & Sunday, 15–16 June, 10 A.M. to 4 P.M.

Governor Gage Comes to Salem

Derby Wharf, Salem

The British army will encamp on the waterfront, with some of New England’s finest living history practitioners portraying soldiers, officers, legislators, and the Loyalist and Patriot citizens of Salem. Over the weekend, visitors can meet people from many walks of life: shoeblacks, teachers, merchants, tavern-keepers, midwives, and more. Activities to be reenacted include military drill, camp cooking, placing ads in a newspaper, and political debate at the tavern.

Here is the full schedule of events.

Sunday, 16 June, 9:00 A.M.

Join the Royal Governor at Church

St. Peter’s Church, Salem

Gen. Gage attended the local Anglican Church when he was in America. In Salem, that meant St. Peter’s, which will recreate an eighteenth-century service with the general occupying the same pew that he used in 1774.

Parliament’s Boston Port Bill took effect on 1 June, and the harbor of Salem and Marblehead became Massachusetts’s largest port open to trade from outside the colony. The Customs office moved there.

Also, Gov. Thomas Gage adjourned the Massachusetts General Court from Boston to Salem, following orders from London. That move didn’t require a new law since the royal governor already had the power to convene the legislature where he chose. That didn’t stop most of the new session being taken up with complaints about being in Salem.

When Gage moved to the region, renting a house in nearby Danvers, he also brought a contingent of British soldiers. There doesn’t appear to have been as much friction between those troops and the locals as in Boston in 1768–1770, but the town governments still raised concerns.

This week the city’s historical organizations are commemorating that period with some public events.

Thursday, 13 June, 7:00 P.M.

Tea’s Party: From Boston to Salem and Back Again

Salem Armory Regional Visitor Center

James R. Fichter speaks about how, despite the so-called Boston Tea Party of 1773, large shipments of tea from the East India Company were sold in North America. The survival of the Boston tea shaped Massachusetts politics in 1774, impeded efforts to reimburse the company for its losses, and hinted at the enduring conflict between consumer demand and political boycotts.

That tension was not confined to Boston. As Gen. Gage and the colonial government relocated to Salem in the summer of 1774, Essex County residents found committing to a boycott just as difficult as Bostonians had.

Fichter is Associate Professor in Global and Area Studies at the University of Hong Kong. He is the author of So Great a Profit: How the East Indies Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism and Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773–1776.

This event is free. For directions, visit this page.

Saturday & Sunday, 15–16 June, 10 A.M. to 4 P.M.

Governor Gage Comes to Salem

Derby Wharf, Salem

The British army will encamp on the waterfront, with some of New England’s finest living history practitioners portraying soldiers, officers, legislators, and the Loyalist and Patriot citizens of Salem. Over the weekend, visitors can meet people from many walks of life: shoeblacks, teachers, merchants, tavern-keepers, midwives, and more. Activities to be reenacted include military drill, camp cooking, placing ads in a newspaper, and political debate at the tavern.

Here is the full schedule of events.

Sunday, 16 June, 9:00 A.M.

Join the Royal Governor at Church

St. Peter’s Church, Salem