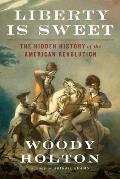

When I first read about the idea that Americans rebelled because they worried about the British government moving to end

chattel slavery,

advanced in books by Alfred and Ruth Blumrosen and Gerald Horne, I didn’t see how that fit the pattern of where the resistance broke out. Nor on where the ensuing Revolution had the greatest effect on slavery.

If the anxiety of slaveholders was a major driver in the onset of the Revolution, why did the worst early confrontations happen in New England, which had the smallest percentage of people enslaved?

Why did that obstreperous

Massachusetts assembly vote twice in the decade before the war to end all imports of human property from Africa? Why did the legislature entertain petitions from enslaved men, reportedly encouraged by its clerk

Samuel Adams? Why did those states move to end or limit slavery during and soon after the war?

Conversely, if slaveholders had become so anxious as to defy the government in London, why did Jamaica and the other

Caribbean islands, which depended completely on chattel slavery, remain firmly loyal to Britain? Why was the British military able to reconquer Georgia and the

capital of South Carolina, two of the three newly independent states with the largest fractions of their populations enslaved?

Those questions apply to the hypothesis that slaveholders were aroused by the

Somerset decision of 1772, as the Blumrosens and Horne argued. And there’s already very little contemporaneous evidence to suggest that white colonists viewed that legal decision as portending any change for America.

On the other hand, if we look at the hypothesis that the slaveholders’ anxiety arose not from the

Somerset case but from the Dunmore and Phillipsburg Proclamations,

as Sylvia Frey, Woody Holton, and others have written, the pattern of resistance makes more sense.

In that view, the early resistance to new taxes, the shift of power in New England in late 1774, and the outbreak of war in 1775 were driven by a lot of other factors—not only

economics and constitutional beliefs but everything from post-Puritan suspicion about the threat of an

Anglican bishop over America to unspoken resentment over more vigorous

Customs enforcement.

Chattel slavery wasn’t necessarily a big factor for American Whigs in that period, except in how Whig philosophy deemed people without traditional British rights as little more than ”slaves,” and the presence of some actual slaves in town might have made that threat feel more real. (Then again, the master class in a slave society is remarkably capable of not seeing themselves as having anything in common with the people they enslave.)

Once fighting began, however, British commanders looked for every resource they could. In late 1775 the

Earl of Dunmore, royal governor of Virginia, promised freedom to people enslaved by Patriots. His offer had power in only one colony, but Virginia wasn’t just any colony—it had the largest total population by far, and over 40% of those people were enslaved.

Dunmore’s campaign was shut down rather quickly, but not before, according to Holton, it pushed Virginians, and perhaps southern Patriots generally, toward independence in 1776. In his first draft of the

Declaration of Independence,

Thomas Jefferson blamed

King George III for perpetuating the slave trade and then wrote:

he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

Southern delegates who wanted to maintain chattel slavery and avoid ridicule for total hypocrisy edited that down to seven words: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us.” The document moved quickly on to complaining about the Crown’s

Native American allies. No one used the word “slave,” but everyone knew “domestic insurrections” meant slave revolts.

The war ground on. Gen.

Henry Clinton renewed Dunmore’s policy in the Phillipsburg Proclamation of 1779 and extended it across all the rebellious colonies. But it had different effects in different regions.

By that point, New England, which already had the least to fear of slave uprisings, was also largely free from the British military. The Phillipsburg Proclamation meant about as little there as the

Somerset decision.

The southern states had become the focus of Clinton’s strategy, and that was also where Patriot and neutral planters saw the most to lose from their human property escaping or rebelling. It makes sense for the biggest backlash against the British to arise there.

As for Jamaica and the rest of the Caribbean, they had never rebelled, so Clinton’s proclamation meant nothing to those planters. The ocean blocked enslaved islanders from seeking freedom behind army lines. The same ocean also made those islands dependent on remaining part of the transatlantic trading system; despite some protests against the

Stamp Act in 1765, the Caribbean planters were never in a position to rebel.

(These thoughts were prompted by Twitter conversation with Woody Holton in early September. He looked at the percentage of enslaved in different colonies. I’ve added the factor of when those places saw the most fighting.)

.jpg/233px-A_map_of_the_most_inhabited_part_of_New_England_(2674889207).jpg)