“The most basic one of all: All men are created equal”

Yesterday I noted and quoted from New York Times Magazine editor Jake Silverstein’s essay about “The 1619 Project,” originally a collection of articles in the Sunday newspaper and now a book.

Silverstein situates that project within the historiography of the American past, and specifically within the effort by some historians to highlight how the Revolutionary conflict included, excluded, and affected people of African descent.

Alongside a longer effort by other historians to ignore or downplay that aspect of the Revolution in order to make the American past look better in the present, whatever the present’s values happen to be at the time.

Here are some more extracts from Silverstein’s discussion:

For anyone who comes away with a hunger for more about the shifting historiography of the American Revolution, check out Michael Hattem’s overview of the subject here and, less graphically, here. Hattem is an educator at Yale and author of Past as Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution.

Silverstein situates that project within the historiography of the American past, and specifically within the effort by some historians to highlight how the Revolutionary conflict included, excluded, and affected people of African descent.

Alongside a longer effort by other historians to ignore or downplay that aspect of the Revolution in order to make the American past look better in the present, whatever the present’s values happen to be at the time.

Here are some more extracts from Silverstein’s discussion:

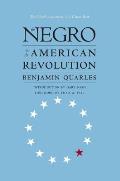

[Benjamin] Quarles’s book “The Negro in the American Revolution,” published in 1961, was an important part of that decade’s historiographical reassessments. It was the first to thoroughly explore an often-overlooked feature of that war: that substantially more Black people were drawn to the British side than the Patriot cause, believing this the better path to freedom.It’s a long essay, with many more interesting passages that I didn’t quote. It might also be paywalled, but I recommend reading it.

Quarles’s work posed profound questions about the traditional narrative of the founding era. While acknowledging that for some white people the ideals of the Revolution had “exposed the inconsistencies” of chattel slavery in a nation founded on equality, he also observed a deeply uncomfortable fact: “They were far outnumbered by those who detected no ideological inconsistency. These white Americans, not considering themselves counterrevolutionary, would never have dreamed of repudiating the theory of natural rights. Instead they skirted the dilemma by maintaining that blacks were an outgroup rather than members of the body politic.”

. . . today we find ourselves back in the midst of another battle over the teaching of American history. Though it differs in some respects from the debate over the national history standards, the two episodes have enough in common that the conclusions drawn by [Gary] Nash and [Charlotte] Crabtree in their 1997 book, “History on Trial: Culture Wars and the Teaching of the Past,” written with Ross E. Dunn, offer some insight into our present struggles. . . . In their view, the standards’ opponents believed that “history that dwells on unsavory or even horrific episodes in our past is unpatriotic and likely to alienate young students from their own country.” Their own perspective was that “exposing students to grim chapters of our past is essential to the creation of informed, responsible citizens.” . . .

It’s a particularly American irony that the effort to do so has been deemed a “divisive concept” and banned from the classroom in 12 states. We may need, instead, legislation that requires us to study divisive concepts, beginning with the most basic one of all: All men are created equal.

As Quarles and others have explained, our founding concept of universal equality, in a country where one-fifth of the population was enslaved, led to an increase in racial prejudice by creating a cognitive dissonance — one that could be resolved only by the white citizenry’s assumption of Black inferiority and inhumanity. It’s an unsettling idea, that the most revered ideal of the Declaration of Independence might be considered our original divisive concept.

For anyone who comes away with a hunger for more about the shifting historiography of the American Revolution, check out Michael Hattem’s overview of the subject here and, less graphically, here. Hattem is an educator at Yale and author of Past as Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment