When

Dr. Benjamin Church wrote his

intelligence report on 24 Sept 1775, the latest big event along the Continental lines was the departure of volunteers heading north.

Those men were under the command of Col.

Benedict Arnold (shown here), respected for his part in taking

Fort Ticonderoga and other Crown positions along Lake Champlain.

Church knew Arnold. In fact, the doctor had been the ranking member of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety who had signed Arnold’s orders for that mission to Ticonderoga on 3 May. In August he headed the committee to review the colonel’s expenses, an interaction that didn’t go so smoothly. (Ironic moments, since Church was already supplying the Crown with secrets and Arnold would do so later.)

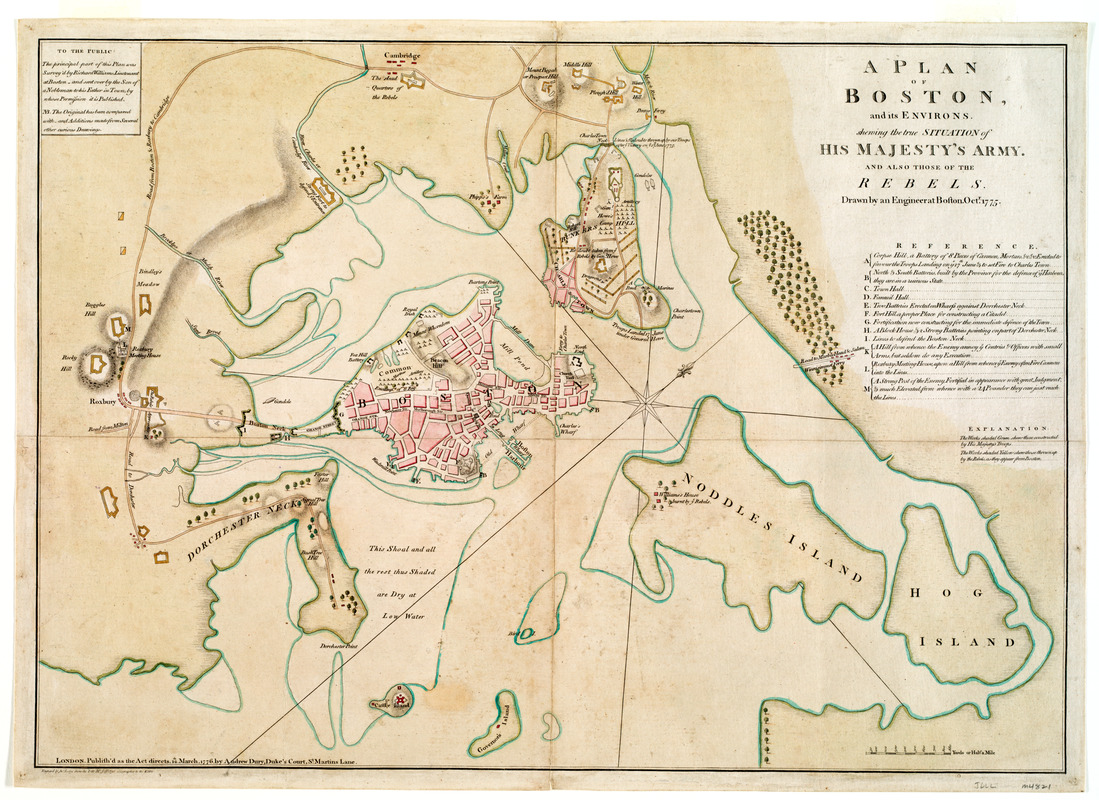

In late August, Arnold met with Gen.

George Washington and gained approval for a quick thrust through

Maine to

Québec, meeting up with Gen.

Richard Montgomery’s force advancing from

New York. The commander’s general orders for 5 September called for “such Volunteers as are active woodsmen, and well acquainted with batteaus,” to march under Arnold’s command. About a thousand men responded, and most of them left

Cambridge on 13 September.

Although the destination of that column was supposed to be secret, lots of people suspected. For example, on 13 September

Jesse Lukens, a volunteer from Pennsylvania, wrote:

Col. Arnold having chosen one thousand effective men, consisting of two companies of riflemen, (about one hundred and forty,) the remainder musqueteers, set off for Quebec, as it is given out, and which I really believe to be their destination. I accompanied on foot as far as Lynn, nine miles.

Starting on 20 September, newspapers in New York and Philadelphia reported on Arnold’s departure for Québec, citing reports from Cambridge. New England newspapers were more cagy about his destination, but the secret was out.

Dr. Church mentioned the overall

Canada campaign three times in his letter, starting with the second sentence and ending just before his request for money:

The fifteen hundred Men that you had news of going to Quebec are going to Halifax (I believe) to destroy that place, . . .

An Express from Ticondiroga, says that they had been Ambushed but foursed their way through with the loss of 13 Men and they on their advancing forward found on the ground ten Indians dead, that the Army was within one Mile and a half of St. Johns, on which they sent a party of Men to Cut of the Communication between Montreal and the Fort. . . .

The Vessells I mentioned that was fiting at Salem was to transport these Men to Kennibeck as I find since, I am not Certain they are gone to Halifax but it is thought and believed they are.

This letter shows that even the British commanders inside Boston had received word of “fifteen hundred Men…going to Quebec” and asked Church about it. But the doctor suspected they were headed to Nova Scotia. When he began this dispatch he was certain about that; by the end, he wasn’t so sure but still thought that was most likely.

In fact, the Continental generals had talked about an attack on Halifax. Immediately after hearing about the shortage of

gunpowder on 3 August, Washington and his council of war discussed raiding Crown outposts with powder stores. Col.

John Glover leased a schooner called the

Hannah.

By mid-September, however, plans had changed. Washington had ordered the

Hannah to try attacking British supply ships instead. He wrote to the merchant

Nathaniel Tracy to arrange for several more

ships to carry Arnold’s one thousand men from

Newburyport up to the mouth of the Kennebeck River.

Church’s expectation of an attack on Halifax might have been accurate at one point, but not any longer.

COMING UP: More details from the Continental camp.

.jpg/161px-Capitol_cupola_Colonial_Williamsburg_(6544791097).jpg)