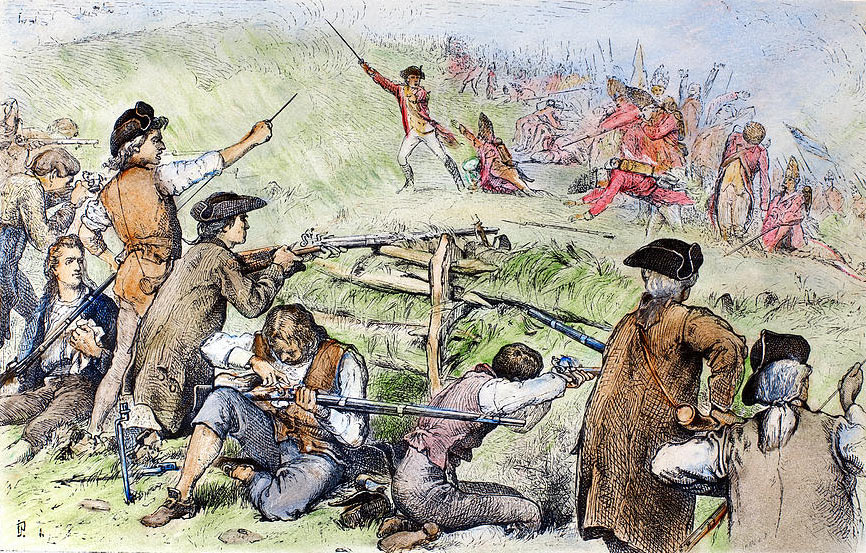

Without army units nearby or a large, full-time police force, no power in the province was strong enough to pacify the mass of ordinary men. Except, that is, a government that accommodated their demands for respect and rights.

In letters to London, those governors offered their diagnoses of how that situation had come about. Gov. William Shirley didn’t say the root of the problem was the Royal Navy forcing sailors and other young men into service. Gov. Francis Bernard didn’t say that Parliament made a mistake in imposing a tax without representation. Those officials said the basic problem was that Boston and Massachusetts’s forms of government were too democratic.

On 1 Dec 1747, Shirley wrote to the Lords of Trade:

But what I think may be esteem’d the principal cause of the Mobbish turn in this Town, is it’s Constitution; by which the Management of it is devolv’d upon the populace assembled in their Town Meetings; one of which may be called together at any time upon the Petition of ten of the meanest Inhabitants, who by their Constant attendance there generally are the majority and outvote the Gentlemen, Merchants, Substantial Traders and all the better part of the Inhabitants; to whom it is Irksome to attend at such meetings, except upon very extraordinary occasions;Here’s Bernard in 1765, arguing for an appointed Council rather than one elected by the Massachusetts elite, in turn elected by the white men of property in their towns:

and by this means it happens, as it would do among any other Community in a Trading Seaport Town under the same Constitution, where there are about Twenty thousand [actually about 16,000] Inhabitants, consisting among others of so many working Artificers, Seafaring Men, and low sort of people, that a factious and Mobbish Spirit is Cherish’d; whereas the same Inhabitants under a different Town-Constitution proper for the Government of so populous and Trading a place, would probably form as well dispos’d a Community for every part of his Majesty’s Service as any the King has under his Government.

The Authority of the King, the Supremacy of Parliament, the Superiority of Government are the real Objects of the attack; and a general levelling of all the powers of Government, & reducing it into the hands of the whole people is what is aimed at, & will, at least in some degree, succeed, without some external assistance.Making the Council appointed instead of elected was one of the big changes of the 1774 Massachusetts Government Act.

The Council, which formerly used to be revered by the people has lost its weight, & notwithstanding their late spirited exertion, is in general timid & irresolute, especially when the Annual Election draws near. That fatal ingredient in the Composition of this Constitution is the bane of the whole: and never will the royal Scale be ballanced with that of the people ’till the Weight of the Council is wholly put into the former. The making the Council independent of the people (even tho’ they should still receive their original Appointment from them) would go far to cure all the disorders which this Government is Subject to.

Thomas Hutchinson was speaker of the house under Gov. Shirley and lieutenant governor and chief justice under Gov. Bernard. He became royal governor himself in 1770 and took up his predecessors’ complaints about the people (i.e., the white men of property) having too much power.

Here’s Hutchinson writing to Bernard on 24 May 1771:

The town of Boston is the source from whence all the other parts of the Province derive more or less troubled water. When you consider what is called its constitution, your good sense will determine immediately that it never can be otherwise for a long time together, whilst the majority which conducts all affairs, if met together upon another occasion, would be properly called a mob, and are persons of such rank and circumstance as in all communities constitute a mob, there being no sort of regulation of voters in practice; and as these will always be most in number, men of weight and value, although they wish to suppress them, cannot be induced to attempt to do it for fear not only of being outvoted, but affronted and insulted. Call such an assembly what you will, it is really no sort of government, not even a democracy, at best a corruption of it.To “compel the town to be a corporation” meant ending the town-meeting form of government and becoming a city with an elected mayor and council—a change Boston eventually made in 1822, to some controversy.

There is no hopes of a cure by any legislative but among ourselves to compel the town to be a corporation. The people will not seek it, because every one is sensible his importance will be lessened. If ever a remedy is found, it must be by compelling them to swallow it, and that by an exterior power,—the Parliament.

Instituting a mandamus Council didn’t quell disturbances in Massachusetts. In fact, it spread them, producing militia uprisings in the countryside within weeks. Ending Boston’s town meetings didn’t end riots in Boston. Instead, American governments became more democratic than the royal governors would have imagined in their worse nightmares, and popular protests became less destructive.