Shepherd is a website founded by Ben Fox to provide a forum for book recommendations, like “little notes from the [indie bookstore] staff about which books are their favorites and why.”

The site offers authors the chance to highlight five books of a particular sort (with some exposure for their own work, of course).

Here are some offerings about America’s Revolutionary era.

Prof. Joel Richard Paul, author of Unlikely Allies: How a Merchant, a Playwright, and a Spy Saved the American Revolution and Without Precedent: Chief Justice Marshall and His Times, on “The best books on the American Revolution.” Mainly solid overviews.

Ray Raphael, author of Founding Myths, Constitutional Myths, A People’s History of the American Revolution, and The Spirit of ’74, among other books, on “The best books to expand and deepen your view of the American Revolution.” Getting beyond the standard stories.

Tom Shachtman, author of The Founding Fortunes: How the Wealthy Paid for and Profited from America’s Revolution, on “The best books on lesser-known figures in the American Revolution and early years.” Following the money.

Prof. James R. Fichter, author of Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773–1776, on “The best books that made me think twice about the American Revolution.” Novel perspectives.

Prof. Richard Bell, author of the new The American Revolution and the Fate of the World, on “The best books on the American Revolution as a World War.” Broader views in space and time.

The Fort Plain Museum bookstore has a Revolutionary War section ranging well beyond its own region in central New York, with generous terms on shipping and the proceeds going to support a historic site.

History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

▼

Wednesday, December 31, 2025

Tuesday, December 30, 2025

“Everything he can to build a standing army that he can use domestically”

Earlier this month, Prof. Noah Shusterman, author of Armed Citizens: From Ancient Rome to the Second Amendment, shared an essay through H.N.N. titled “Deploying Federal Troops to U.S. Cities Is a Second Amendment Issue.”

Here’s a taste:

The President claims this authority based on laws speaking of “invasion” and “rebellion,” neither of which applies, and he also claims he’s acting against “crime.” This same President is a convicted criminal who pardoned about 1,600 people for attacking the U.S. Capitol on his behalf in January 2021.

Here’s a taste:

The Second Amendment was meant to prevent events like the Boston Massacre… The amendment was meant to prevent the government from turning its military into an occupying force, as the British were doing when they began stationing troops in Boston. It is also what our current president is trying to do when he sends federal troops into Los Angeles. Or Portland. Or Chicago. Or, eventually, New York and Boston.I write this from Washington, D.C., where the President has summoned over 2,600 National Guard troops from multiple states. While traveling to libraries, I see small groups of young people in uniform pulled away from their homes and jobs to stand around in subway stations and parks. Courts have disagreed about the constitutionality of that order and others, with the President getting even more deference than usual in the federal district.

The courts have been treating those deployments as Tenth Amendment issues, or as potential violations of the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act, but back when the Bill of Rights was written, the domestic deployment of federal troops was the Second Amendment issue. And if the courts understood that, we would be in much less of a mess right now. In 2025, the amendment might be about privately owned guns, but when the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791, it was about the military — specifically, the threat that a nation’s military could pose to its own people, as it had in Boston during the 1770s, when the British government began stationing troops there. . . .

In the years immediately following independence, neither the state militias’ shortcomings on the battlefield during the Revolution, nor the Continental Army’s successes, made Americans any less wary of peacetime standing armies. Leaders of the founding generation still believed that because a professional soldier relied on his job for his livelihood, his allegiance was to his commander, not his nation. (The current commander-in-chief recently endorsed this view, albeit unknowingly, when he told an audience of military leaders that “if you don’t like what I’m saying, you can leave the room. Of course, there goes your rank, there goes your future.”) . . .

In Second Amendment terms, this president is doing everything he can to build a standing army that he can use domestically against his own population. If the Second Amendment’s self-proclaimed supporters both inside and outside the courts appreciated the significance of these policies, and how contrary they are to the amendment’s original goals, the nation might be in a better place right now. In deploying federal police and military units as an occupying force, the president is doing precisely what the amendment was meant to prevent.

The President claims this authority based on laws speaking of “invasion” and “rebellion,” neither of which applies, and he also claims he’s acting against “crime.” This same President is a convicted criminal who pardoned about 1,600 people for attacking the U.S. Capitol on his behalf in January 2021.

Monday, December 29, 2025

Wartime with “A New-York Freeholder”

“A New-York Freeholder” didn’t continue his newspaper debate with Israel Putnam, quoted over the last two days.

Hugh Gaine had published long essays from the “Freeholder” addressed “To the Inhabitants of North-America” in five successive issues of the New-York Gazette from 12 September to 10 October. One of those essays even crowded out other items.

The main target of the “Freeholder” was the Continental Congress and the ideology that led to it. His last essay criticized military preparations in New England and calls for non-importation. He treated Putnam’s letter about the “Powder Alarm” as simply a symptom of a deeper problem.

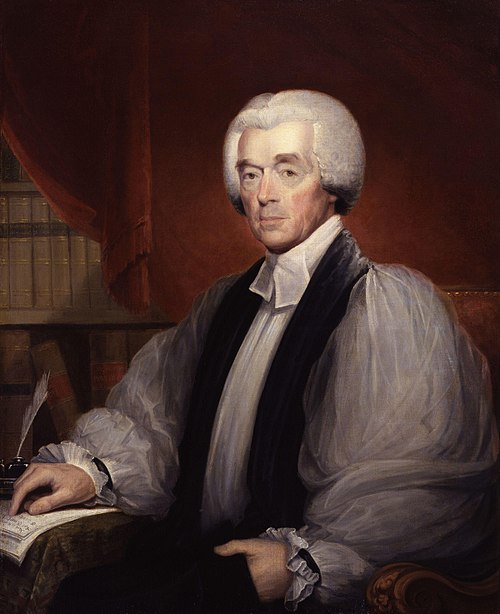

The “New-York Freeholder” was the Rev. Charles Inglis (1734–1816), recently made the senior curate at Trinity Church in New York. He was a native of Ireland but attached to the Anglican Church, even arguing for the unpopular idea of bishops in North America.

(This was not the Charles Inglis who commanded H.M.S. Lizard in 1770–71, H.M.S. Salisbury in 1778–80, and H.M.S. St. Albans in 1780–83, and who made one previous appearance on Boston 1775.)

According to the Rev. Mr. Inglis, he ceased his “Freeholder” essays after deciding that the Congress was hopelessly committed to “revolt and independency,” based on its adoption of the Suffolk Resolves and the proclamations it issued in mid-October 1774. So he never responded to Putnam.

After Thomas Paine issued Common Sense in early 1775, Inglis composed a reply titled The Deceiver Unmasked, printed by Samuel Loudon. Soon after copies were advertised for sale, Patriots broke into Loudon’s shop, seized all the copies, and burned them. Inglis was able to have the pamphlet reprinted in Philadelphia under the title The True Interest of America Impartially Stated.

In mid-1776, Gen. George Washington attended Trinity Church. As the minister told it, a lesser American general asked him to omit the usual prayers for the king from the service. Inglis defiantly refused. A few months later, the British military kicked the Continentals out of the city.

Inglis spent the rest of the war inside British-occupied New York, having become the rector of Trinity Church. In June–July 1782 he pulled out the “New-York Freeholder” name again for six essays in Rivington’s New-York Gazette.

The next year Inglis and his family moved to Britain, though most of the Trinity Church congregation went to Halifax. In 1787 the Crown sent him back across the Atlantic to be bishop of Nova Scotia—the first Anglican bishop in North America.

Hugh Gaine had published long essays from the “Freeholder” addressed “To the Inhabitants of North-America” in five successive issues of the New-York Gazette from 12 September to 10 October. One of those essays even crowded out other items.

The main target of the “Freeholder” was the Continental Congress and the ideology that led to it. His last essay criticized military preparations in New England and calls for non-importation. He treated Putnam’s letter about the “Powder Alarm” as simply a symptom of a deeper problem.

The “New-York Freeholder” was the Rev. Charles Inglis (1734–1816), recently made the senior curate at Trinity Church in New York. He was a native of Ireland but attached to the Anglican Church, even arguing for the unpopular idea of bishops in North America.

(This was not the Charles Inglis who commanded H.M.S. Lizard in 1770–71, H.M.S. Salisbury in 1778–80, and H.M.S. St. Albans in 1780–83, and who made one previous appearance on Boston 1775.)

According to the Rev. Mr. Inglis, he ceased his “Freeholder” essays after deciding that the Congress was hopelessly committed to “revolt and independency,” based on its adoption of the Suffolk Resolves and the proclamations it issued in mid-October 1774. So he never responded to Putnam.

After Thomas Paine issued Common Sense in early 1775, Inglis composed a reply titled The Deceiver Unmasked, printed by Samuel Loudon. Soon after copies were advertised for sale, Patriots broke into Loudon’s shop, seized all the copies, and burned them. Inglis was able to have the pamphlet reprinted in Philadelphia under the title The True Interest of America Impartially Stated.

In mid-1776, Gen. George Washington attended Trinity Church. As the minister told it, a lesser American general asked him to omit the usual prayers for the king from the service. Inglis defiantly refused. A few months later, the British military kicked the Continentals out of the city.

Inglis spent the rest of the war inside British-occupied New York, having become the rector of Trinity Church. In June–July 1782 he pulled out the “New-York Freeholder” name again for six essays in Rivington’s New-York Gazette.

The next year Inglis and his family moved to Britain, though most of the Trinity Church congregation went to Halifax. In 1787 the Crown sent him back across the Atlantic to be bishop of Nova Scotia—the first Anglican bishop in North America.

Sunday, December 28, 2025

“Under the hieroglyphical similitude of tropes and figures?”

As a prominent gentleman in Connecticut, Israel Putnam couldn’t ignore what “A New-York Freeholder” wrote about him in the New-York Gazette, as quoted yesterday.

However, Putnam faced a couple of challenges in replying. First, if he appeared to be flying off the handle, that would simply validate what the “Freeholder” had written.

Second, Putnam wasn’t a highly educated man, and in particular his spelling and punctuation were even more irregular than the eighteenth-century norm.

Even Putnam’s biographers acknowledge that he probably had help in shaping his reply in the 7 October 1774 Connecticut Gazette of New London, either from a friend or from printer Timothy Green. Because it doesn’t look like his usual writing.

The preface reads:

Putnam described how the rumor of a British military attack on Boston had reached him through “Capt. Keyes”—most likely Stephen Keyes (1717–1788, gravestone shown above courtesy of Find a Grave). Keyes had heard the news from “Capt. Clarke of Woodstock,” who heard from his son in Dudley, Massachusetts, who heard from an Oxford man named Wilcot, who heard from his father and also found confirmation in Grafton.

With “only four gentlemen,” Putnam rode toward Boston, traveling “about thirty miles from my house.” In Douglas, Massachusetts, the party met the local militia captain, probably Caleb Hill (1716–1788), who with his company had just returned from their own march to “within about thirty miles of Boston.” Having thus learned that the earlier report was false, Putnam returned home, spreading the new word.

Putnam posited that the false alarm started with Customs Commissioner Benjamin Hallowell having “informed the army that he had killed one man and wounded another” while escaping from Cambridge. Hallowell’s own account of the “Powder Alarm” said nothing of the sort.

As for presenting himself as a gentleman in prose, Putnam acknowledged that he’d written his letter passing on that misinformation in haste and not in high style; he said he “aimed at nothing but plain matters of fact, as they were delivered to him.”

But Putnam also showed himself capable of deploying complex sentences and classical allusions in response to the “New-York Freeholder”:

TOMORROW: Who was the “New-York Freeholder”?

However, Putnam faced a couple of challenges in replying. First, if he appeared to be flying off the handle, that would simply validate what the “Freeholder” had written.

Second, Putnam wasn’t a highly educated man, and in particular his spelling and punctuation were even more irregular than the eighteenth-century norm.

Even Putnam’s biographers acknowledge that he probably had help in shaping his reply in the 7 October 1774 Connecticut Gazette of New London, either from a friend or from printer Timothy Green. Because it doesn’t look like his usual writing.

The preface reads:

Mr. GREEN,The first line of the ensuing essay makes clear what it was really responding to: “In Mr. [Hugh] Gaine’s New-York Gazette of the 12th of September…”

As my letter to Capt. [Aaron] Cleveland, wrote in consequence of the late alarm, has circulated far and wide, and made unfavourable impressions on the minds of some, ’tis desired that you and the several printers in the other colonies upon the continent, would give the following piece a place in your paper, and you will oblige

Your humble Servant,

ISRAEL PUTNAM.

POMFRET, 3d. October 1774.

Putnam described how the rumor of a British military attack on Boston had reached him through “Capt. Keyes”—most likely Stephen Keyes (1717–1788, gravestone shown above courtesy of Find a Grave). Keyes had heard the news from “Capt. Clarke of Woodstock,” who heard from his son in Dudley, Massachusetts, who heard from an Oxford man named Wilcot, who heard from his father and also found confirmation in Grafton.

With “only four gentlemen,” Putnam rode toward Boston, traveling “about thirty miles from my house.” In Douglas, Massachusetts, the party met the local militia captain, probably Caleb Hill (1716–1788), who with his company had just returned from their own march to “within about thirty miles of Boston.” Having thus learned that the earlier report was false, Putnam returned home, spreading the new word.

Putnam posited that the false alarm started with Customs Commissioner Benjamin Hallowell having “informed the army that he had killed one man and wounded another” while escaping from Cambridge. Hallowell’s own account of the “Powder Alarm” said nothing of the sort.

As for presenting himself as a gentleman in prose, Putnam acknowledged that he’d written his letter passing on that misinformation in haste and not in high style; he said he “aimed at nothing but plain matters of fact, as they were delivered to him.”

But Putnam also showed himself capable of deploying complex sentences and classical allusions in response to the “New-York Freeholder”:

Paying all due defference to this author’s learning, and his undoubted acquaintance with the rules of grammar and criticism, I would beg leave to ask him, whether he does not betray a total want of the feelings of humanity, if he supposes in the midst of confusion, when the passions are agitated with a real belief of thousands of their fellow countrymen being slain, & the inhabitants of a whole city just upon the eve of being made a sacrifice by the rapine and fury of a merciless soldiery, and their city laid in ashes by the fire of ships of war, he or any one else could set down under the possession of a calmness of soul becoming a Roman senator, and attend to all the rules of composition, in writing a letter, to make a representation of plain matters of facts, under the hieroglyphical similitude of tropes and figures? . . .Well, when he put it that way…

Now I submit it to the determination of every candid unprejudiced reader, whether my conduct in writing the aforementioned letter, merits the imputation of imprudence asserted by said writer; or whether they would have had me tamely set down, and been a spectator to the unhuman sacrifice of my friends and fellow-countrymen, or (in other words) Nero like, have set down and fiddled, while I really supposed Boston was in flames, or exerted myself for their relief?

TOMORROW: Who was the “New-York Freeholder”?

Saturday, December 27, 2025

“This letter betrays the state of the poor Colonel’s mind”

One of the key nodes in the spread of the “Powder Alarm” was Israel Putnam. On 3 Sept 1774 he summoned the militia in eastern Connecticut and sent urgent messages to other parts of the colony.

One of the key nodes in the spread of the “Powder Alarm” was Israel Putnam. On 3 Sept 1774 he summoned the militia in eastern Connecticut and sent urgent messages to other parts of the colony. On 6 September one of those messages arrived at the First Continental Congress. Robert Treat Paine recorded that from Putnam’s letter “we were informed that the Soldiers had fired on the People and Town at Boston.”

In fact, British soldiers had done no such thing. That became clear over the next few days.

Whigs spun the false alarm into a Good Thing, saying it showed how the populace was united and ready to defend Boston in an actual military emergency. “It is surprising and must give great satisfaction to every well-wisher to the liberties of his country, to see the spirit and readiness of the people to fly to the relief of their distressed brethren,” said an item in the 9 September Connecticut Gazette.

But other newspaper writers were more critical. Most of the front page of Hugh Gaine’s New-York Gazette on 19 September was filled with an open letter “To the Inhabitants of North-America” from “A New-York Freeholder” that said in part:

Col. PUTNAM’s famous letter, (forwarded by special messengers to New-York and Philadelphia) and the consequences it produced, are very recent and fresh in our memories. He informs Capt. [Aaron] Cleaveland [of Canterbury]---The “New-York Freeholder” went on to write about the horrors of a civil war, closing with Tobias Smollett’s poem “The Tears of Scotland,” composed after the Jacobite uprising of 1745. That would have annoyed the New England Whigs, not just because they were telling people that a firm, unified militia response would help stave off civil war but also because they hated being equated with Jacobites.“That the men of war and troops had fired on Boston—that the artillery played all night—that six were filled at the first shot, and a number wounded—that the people were universally rallying from Boston as far as Pomfret in Connecticut—and he begs the captain would rally all the forces he could, and march immediately for the relief of Boston.”The evident confusion of ideas in this letter betrays the state of the poor Colonel’s mind, whilst writing it, and shews he did not then possess that calm fortitude which is so necessary to insure success in military enterprizes. . . .

What the design of this infamous report was—whether to inflame the other colonies, and to learn how they would act on such an emergency if real, or to influence the deliberations of our congress now sitting, I shall not taken upon me to determine.

One thing it has eventually made evident past all doubt, that many in the New-England colonies are disposed and ripe for the most violent measures: For it is certain that some thousands of armed men, in consequence of it, proceeded on their march from Connecticut towards Boston. . . .

These circumstances are mentioned with no other view than to shew that the apprenhension of a civil war is justly founded; and it is no more than justice to say that I think Col. PUTNAM himself was deceived when he wrote the above letter, tho’ still he acted imprudently in writing it. The authors of the report are to me unknown.

TOMORROW: How Putnam responded.

Friday, December 26, 2025

“The Powder Alarm” in Essex, Connecticut, on 4 Jan.

I’ll start off the Sestercentennial year with a talk in the America 250 Winter Lecture Series of the historical society in Essex, Connecticut.

My topic on the afternoon of Sunday, 4 Jan 2026, will be “The Powder Alarm: The Breakdown of Royal Rule in New England, September 1774.”

Here’s our event description:

Here’s an account of the colony’s reaction from the 8 Sept 1774 Massachusetts Spy:

Nonetheless, it’s clear the alarm was widespread, reflecting the urgency that people had come to feel about what was happening in Massachusetts. Several other newspaper articles about the “Powder Alarm” also included the phrase “a minute’s warning,” popularizing it just as citizens were discussing how to improve their militia system.

This talk is scheduled to run from 3:30 to 4:30 P.M. in Hamilton Hall at Essex Meadows, 30 Bokum Road in Essex, Connecticut. It’s free and open to the public. The society asks people to register through this page. Doors will open at 3 P.M., and seating will be on a first-come, first-served basis.

(The modern town of Essex appears on the map above as “Putty Pogue” on the Connecticut River.)

My topic on the afternoon of Sunday, 4 Jan 2026, will be “The Powder Alarm: The Breakdown of Royal Rule in New England, September 1774.”

Here’s our event description:

Before dawn on September 1, 1774, the royal governor of Massachusetts ordered some of the colony’s gunpowder moved into army-occupied Boston. That action put thousands of militiamen on the march. As rumors spread, they grew more dire. People in Connecticut heard that the king’s army and navy had attacked Boston. In Milford, a 13-year-old boy went to bed fearing he would “be dead or a captive before to-morrow morning.” But the real result of this event, dubbed the “Powder Alarm” by later historians, was that almost all of New England was free of royal rule—almost two years before the Declaration of Independence.I’ve spoken about the “Powder Alarm” before, and this time I’ll emphasize Connecticut’s experience through figures like Israel Putnam, Silas Deane, and Joseph Plumb Martin.

Here’s an account of the colony’s reaction from the 8 Sept 1774 Massachusetts Spy:

By letters from Connecticut, and by several credible gentlemen arrived from thence, we are informed that there were not less than 40,000 men, in motion, and under arms, on their way to Boston, on Saturday, Sunday, and Monday last [3–5 September], having heard a false report that the troops had fired upon Boston, and killed several of the inhabitants: Twelve hundred arrived at Hartford from Farmington, and other places forty miles beyond Hartford, on Sunday last, on their way to this place, so rapidly did the news fly. But being informed by expresses that it was a false report, they returned home, declaring themselves ready at a minute’s warning to arm again, and fight for their country, and distressed brethren of Boston.That report from printer Isaiah Thomas was no doubt exaggerated. In 1774 Connecticut’s total population was just under 200,000. More than half of those people were under the age of sixteen, and half the adults were women, so “no less than 40,000 men” would be virtually the entire adult male population.

Nonetheless, it’s clear the alarm was widespread, reflecting the urgency that people had come to feel about what was happening in Massachusetts. Several other newspaper articles about the “Powder Alarm” also included the phrase “a minute’s warning,” popularizing it just as citizens were discussing how to improve their militia system.

This talk is scheduled to run from 3:30 to 4:30 P.M. in Hamilton Hall at Essex Meadows, 30 Bokum Road in Essex, Connecticut. It’s free and open to the public. The society asks people to register through this page. Doors will open at 3 P.M., and seating will be on a first-come, first-served basis.

(The modern town of Essex appears on the map above as “Putty Pogue” on the Connecticut River.)

Thursday, December 25, 2025

John Rowe’s Christmas Gift to Himself

On 25 December 1775, 250 years ago today, the Boston merchant John Rowe began a new volume of his daily diary.

The Massachusetts Historical Society has preserved and digitized that document, so that page is available here with a good crowd-sourced transcription.

Rowe wrote:

Rowe’s diary entry for this day is innocuous. This volume raises questions mainly in how the previous volume, covering the days from 1 June to 24 December 1775, is missing. What did Rowe do during the siege? How closely did he cooperate with the royal authorities? What sentiments did he express about the Battle of Bunker Hill and other fatal fights?

The only previous volume of the diary to go missing covered 18 Aug 1765 to 10 Apr 1766, a gap starting shortly before the attack on Thomas Hutchinson’s house. (The lieutenant governor suspected Rowe was somehow behind that attack.) Rowe’s numbering indicates that he filled 138 pages in those eight months.

In contrast, Rowe wrote only 72 pages in the missing volume from late 1775, which would be by far the shortest volume in his journal. Still, those pages would be good to have.

We know John Rowe altered a 1775 diary entry to reverse what he first wrote about the Massachusetts Provincial Congress’s fast day. We know his description of his speech during one of the 1773 tea meetings doesn’t match what an observer in the room reported. It’s easy to imagine, therefore, that Rowe at some point looked at what he wrote about the Stamp Act and its opponents, and about the early months of the war, and decided that those pages no longer reflected his views. Or how he wanted people to view him.

The Massachusetts Historical Society has preserved and digitized that document, so that page is available here with a good crowd-sourced transcription.

Rowe wrote:

Monday December 25. 1775 Christmas Day — The Weather A Little Moderated but Cold W W —Rowe was an Anglican, a vestryman at Trinity Church. Unlike the colony’s more numerous Congregationalists, he and his fellow parishioners observed Christmas. But of course Christmas in a besieged town wasn’t a terrifically joyous occasion; “Peace [and] Good Will towards Men” were in short supply.

I went to Church this morning. Mr. [William] Walter Read prayers & Mr [Samuel] Parker preachd A very Good Sermon from the 2d Chapter of St Lukes Gospell and 14th. Verse Glory to God in the Highest and on Earth Peace Good Will towards Men.

I dind at home with Mrs. Rowe the Revd Mr Parker & Jack Rowe and spent the Evening at home with Richd Greene Mrs. Rowe & Jack Rowe

I Staid & partook of the Sacrament

The Mony gather’d for the Use of the Poor of this church amo to Sixty Dollars —

Rowe’s diary entry for this day is innocuous. This volume raises questions mainly in how the previous volume, covering the days from 1 June to 24 December 1775, is missing. What did Rowe do during the siege? How closely did he cooperate with the royal authorities? What sentiments did he express about the Battle of Bunker Hill and other fatal fights?

The only previous volume of the diary to go missing covered 18 Aug 1765 to 10 Apr 1766, a gap starting shortly before the attack on Thomas Hutchinson’s house. (The lieutenant governor suspected Rowe was somehow behind that attack.) Rowe’s numbering indicates that he filled 138 pages in those eight months.

In contrast, Rowe wrote only 72 pages in the missing volume from late 1775, which would be by far the shortest volume in his journal. Still, those pages would be good to have.

We know John Rowe altered a 1775 diary entry to reverse what he first wrote about the Massachusetts Provincial Congress’s fast day. We know his description of his speech during one of the 1773 tea meetings doesn’t match what an observer in the room reported. It’s easy to imagine, therefore, that Rowe at some point looked at what he wrote about the Stamp Act and its opponents, and about the early months of the war, and decided that those pages no longer reflected his views. Or how he wanted people to view him.

Wednesday, December 24, 2025

John Malcom, Counterfeiter?

Watching the recent American Revolution documentary series by Ken Burns, Sarah Botstein, and David Schmidt, my ear snagged on a detail about John Malcom.

The show said that Malcom, the Customs service officer severely mobbed, tarred, feathered, and whipped in Boston in January 1774, had gotten in trouble for counterfeiting a decade earlier.

Since I’ve collected newspaper reports about John Malcom for a series of postings I really must get back to, I was surprised at not having come across a report of that crime. Whig printers enjoyed publishing stories about Malcom’s behavior after he joined the Customs service. They had even more reason to pull out embarrassing old stories after the attack on him. But no newspaper described Malcom as a counterfeiter.

In Scars of Independence (2017) Holger Hoock wrote of Malcom: “He had become notorious across the colonies after being arrested for debt and counterfeiting in 1763.” Given the lack of newspaper mentions, the captain definitely wasn’t notorious for such a crime. In fact, after further research I’m dubious the man was ever charged with counterfeiting at all.

The earliest mentions of such a crime appear the work of Dirk Hoerder: his 1971 doctoral thesis, “People and Mobs, Crowd Action in Massachusetts During the American Revolution 1765–1780,” and his 1977 book, Crowd Action in Revolutionary Massachusetts, 1765-1780. The latter says of Malcom: “In 1763 he had been apprehended in Boston for debt and counterfeiting.”

The citation for that sentence appears to be Suffolk Court Files 84397, which is a court case listed as Malcom v. Butters. That doesn’t look like a criminal charge for counterfeiting, though it could well be a debt dispute. I haven’t seen that paperwork, though.

Based on newspaper reports, Capt. John Malcom spent little time in Boston in the 1760s. He had moved to Québec and commanded trading voyages to the West Indies. Of course, Malcom might have been charged or sued during a brief stopover in his home town.

Yet we have to be careful we have the right John Malcom. The 15 October 1772 Boston News-Letter announced the death of “Mr. John Malcom, Labourer,” as did the following Monday’s Boston Post-Boy and Boston Evening-Post. Obviously that wasn’t the Customs officer attacked in 1774. But he might have been the debtor of 1763.

Further confusing matters is how a “John Malcom, alias Malcolm,” was convicted of passing counterfeit bills in Maryland—back in 1743. (Kenneth Scott’s Maryland Historical Magazine article “Counterfeiting in Colonial Maryland,” which can be downloaded in a P.D.F. here, misdates that case as in 1734.)

Normally I find Hoerder’s work to be very thorough and reliable. In this case, however, I think that he (if you’ll excuse the expression) tarred the wrong John Malcom with the wrong misdeeds.

The show said that Malcom, the Customs service officer severely mobbed, tarred, feathered, and whipped in Boston in January 1774, had gotten in trouble for counterfeiting a decade earlier.

Since I’ve collected newspaper reports about John Malcom for a series of postings I really must get back to, I was surprised at not having come across a report of that crime. Whig printers enjoyed publishing stories about Malcom’s behavior after he joined the Customs service. They had even more reason to pull out embarrassing old stories after the attack on him. But no newspaper described Malcom as a counterfeiter.

In Scars of Independence (2017) Holger Hoock wrote of Malcom: “He had become notorious across the colonies after being arrested for debt and counterfeiting in 1763.” Given the lack of newspaper mentions, the captain definitely wasn’t notorious for such a crime. In fact, after further research I’m dubious the man was ever charged with counterfeiting at all.

The earliest mentions of such a crime appear the work of Dirk Hoerder: his 1971 doctoral thesis, “People and Mobs, Crowd Action in Massachusetts During the American Revolution 1765–1780,” and his 1977 book, Crowd Action in Revolutionary Massachusetts, 1765-1780. The latter says of Malcom: “In 1763 he had been apprehended in Boston for debt and counterfeiting.”

The citation for that sentence appears to be Suffolk Court Files 84397, which is a court case listed as Malcom v. Butters. That doesn’t look like a criminal charge for counterfeiting, though it could well be a debt dispute. I haven’t seen that paperwork, though.

Based on newspaper reports, Capt. John Malcom spent little time in Boston in the 1760s. He had moved to Québec and commanded trading voyages to the West Indies. Of course, Malcom might have been charged or sued during a brief stopover in his home town.

Yet we have to be careful we have the right John Malcom. The 15 October 1772 Boston News-Letter announced the death of “Mr. John Malcom, Labourer,” as did the following Monday’s Boston Post-Boy and Boston Evening-Post. Obviously that wasn’t the Customs officer attacked in 1774. But he might have been the debtor of 1763.

Further confusing matters is how a “John Malcom, alias Malcolm,” was convicted of passing counterfeit bills in Maryland—back in 1743. (Kenneth Scott’s Maryland Historical Magazine article “Counterfeiting in Colonial Maryland,” which can be downloaded in a P.D.F. here, misdates that case as in 1734.)

Normally I find Hoerder’s work to be very thorough and reliable. In this case, however, I think that he (if you’ll excuse the expression) tarred the wrong John Malcom with the wrong misdeeds.

Tuesday, December 23, 2025

“In free countries, the law ought to be king”

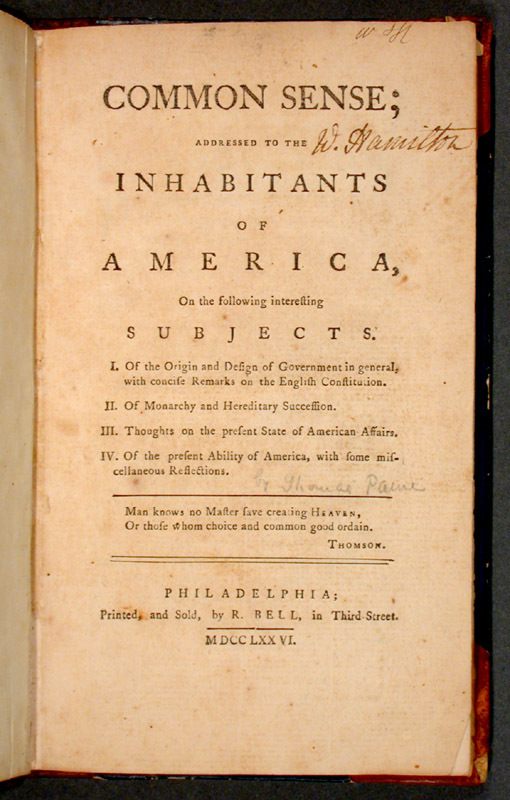

Next month sees the Sestercentennial of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, printed by Robert Bell in Philadelphia on 9 January (to judge by the first newspaper advertisement the next day) and then reprinted at the end of the month because of popular demand.

The New York Times has observed the occasion by publishing an appreciation by Boston University professor Joseph Rezek, “The Pamphlet That Has Roused Americans to Action for 250 Years.”

Rezek’s a literature scholar, so he pays particular attention to Paine’s rhetorical style. Here’s a taste:

Here’s the link.

The New York Times has observed the occasion by publishing an appreciation by Boston University professor Joseph Rezek, “The Pamphlet That Has Roused Americans to Action for 250 Years.”

Rezek’s a literature scholar, so he pays particular attention to Paine’s rhetorical style. Here’s a taste:

The first section of “Common Sense” narrates the origins of government with a classic Enlightenment experiment, asking: What was it like in the state of nature, before governments were instituted among people? “Let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the earth” in a “state of natural liberty,” Paine wrote, sounding like a schoolteacher. Then kings arrive, like snakes in the garden.Of course, it’s not just the lèse-majesté insults that made Common Sense powerful, as shocking as they probably were to some British colonists. It was how Paine wielded them in service of compelling political ideas, urging Americans to put their principles of liberty into practice. A monarchist could toss around epithets and still have no better argument than “Because the king said so.”

“Mankind being originally equals,” Paine went on, their “equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance.” Look at the “present race of kings,” he declared, and “we should find the first of them nothing better than the principal ruffian of some restless gang.” Eager to make his ideas intelligible to readers who had never philosophized before, Paine used imagery he thought they could relate to.

Ripping up monarchy by the roots, he asserted that William the Conqueror did not establish an “honorable” origin for English kings when he invaded in 1066. “A French bastard landing with an armed banditti, and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives, is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original. It certainly hath no divinity in it.” This frank and gritty language is from the tavern, not the library.

In 1776, Paine looked toward the future. Today, many Americans are looking to the past to help navigate what really does feel like “a new era for politics.” Right after Paine declared “the law is king,” he also qualified that statement: “In free countries, the law ought to be king.” Laws in the United States have often been unjust, and just laws have often been unequally enforced. Perhaps Paine understood that the idealistic political experiment he hoped to help launch would always be a work in progress.Because there will always be snakes. Most of us know damn well they’re snakes, and most don’t get taken in.

Here’s the link.

Monday, December 22, 2025

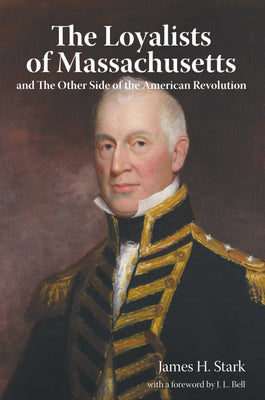

New Foreword for Stark’s Loyalists of Massachusetts

American Ancestors has just reissued James Henry Stark’s The Loyalists of Masssachusetts with a new foreword by me.

I came across a copy of Stark’s Loyalists of Massachusetts in my local library when I was early in my research on eighteenth-century Boston. I was struck by its combination of detailed research on exiled families and apparently still-hot resentment at how the whole Revolution thing turned out.

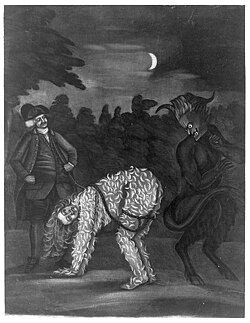

One notorious detail of this book is an illustration of Paul Revere on horseback—complete with fringed buckskin coat, beard, and vicious snarl.

In researching the publication of The Loyalists of Massachusetts for this foreword, I realized that Stark didn’t commission that and the other full-page illustrations. He reused them from an earlier history of the Revolution. He did, however, change the captions to make their message more pointed.

Stark published through his own printing company, which he had cofounded with a former “spirit photographer.” That gave him the freedom to devote hundreds of pages to “The Other Side of the American Revolution,” as his subtitle said.

I also looked into the reception of the book in 1910. Some reviewers thought Stark, a childhood immigrant from Britain, was too harsh on the Patriots. The press magnified that controversy. The argument became a front-page story in newspapers well outside New England as editors enjoyed the spectacle of elite Bostonians arguing over their ancestors’ actions.

Another of Stark’s interests was yachting. In fact, he was on a cruise when the controversy over his book broke out. I think he’d be pleased that the cover of this new edition shows Sir Isaac Coffin, alumnus of Boston’s South Latin School and admiral in the Royal Navy.

I came across a copy of Stark’s Loyalists of Massachusetts in my local library when I was early in my research on eighteenth-century Boston. I was struck by its combination of detailed research on exiled families and apparently still-hot resentment at how the whole Revolution thing turned out.

One notorious detail of this book is an illustration of Paul Revere on horseback—complete with fringed buckskin coat, beard, and vicious snarl.

In researching the publication of The Loyalists of Massachusetts for this foreword, I realized that Stark didn’t commission that and the other full-page illustrations. He reused them from an earlier history of the Revolution. He did, however, change the captions to make their message more pointed.

Stark published through his own printing company, which he had cofounded with a former “spirit photographer.” That gave him the freedom to devote hundreds of pages to “The Other Side of the American Revolution,” as his subtitle said.

I also looked into the reception of the book in 1910. Some reviewers thought Stark, a childhood immigrant from Britain, was too harsh on the Patriots. The press magnified that controversy. The argument became a front-page story in newspapers well outside New England as editors enjoyed the spectacle of elite Bostonians arguing over their ancestors’ actions.

Another of Stark’s interests was yachting. In fact, he was on a cruise when the controversy over his book broke out. I think he’d be pleased that the cover of this new edition shows Sir Isaac Coffin, alumnus of Boston’s South Latin School and admiral in the Royal Navy.

Sunday, December 21, 2025

The Burdicks after the Boston Massacre

In the year after the Boston Massacre, Benjamin Burdick became the proprietor of the Freemason’s Arms tavern—better known as the Green Dragon Tavern, owned by the St. Andrew’s lodge.

I imagine his wife Jane did a lot of the hosting since Benjamin remained Constable of the Town House Watch through 1774.

As the London government cracked down and war approached, the Burdicks moved out to Marblehead. Benjamin opened a “large, genteel, and commodious” inn opposite Jeremiah Lee’s mansion. Soon he was watching over auctions of captured goods and vessels. Later the inn hosted auctions of estates confiscated from absent Loyalists.

By 1786 Burdick had relocated to Danvers, at the Sign of the Flag, but that property was sold the next year. Jane was back in Boston when she died in 1791. I haven’t found a record of Benjamin’s death. (It doesn’t help that genealogists have intertwined him with a man of the same name from Westerly, Rhode Island.)

In 1778, the Boston merchant Samuel Phillips funded the opening of a new academy in Andover with Eliphalet Pearson as preceptor. The inaugural class of that school included Malcolm McNeil Burdick, born in Boston 1764—the Burdicks’ oldest son. (His first and middle name appeared with different spellings.) Malcolm was in his teens but for some reason listed as age ten in school records.

Later Malcolm M. Burdick went to sea, appearing in advertisements as master of the Minerva sailing from Baltimore to Liverpool in 1801 and of the John out of New York in 1807. By 1812 he had settled in Windham, Maine, where he advertised that someone else’s livestock had gotten onto his land.

Another of Benjamin and Jane Burdick’s sons, William, born in 1774, went into printing. In July 1795 he and Benjamin Sweetser cofounded a newspaper in Boston called the Courier. Soon that became The Courier, Boston Evening Gazette and Universal Advertiser. Burdick signed over his portion of the business to Sweetser in December, and it ceased publishing in March 1796 after a fire.

[ADDENDUM: From 1798 to 1800 William Burdick was the junior partner in publishing the Oriental Trumpet newspaper in Portland, Maine. He then returned to Boston.]

In 1809 William Burdick married Lucretia Sprague (1788–1849), daughter of Continental artillery veteran Samuel Sprague (1753–1844). According to her brother, the banker and poet Charles Sprague (1791–1895), their father was also part of the Boston Tea Party.

William Burdick reused the Boston Evening Gazette name for a new periodical in 1813. His printing office at Congress and State Streets was next to the Exchange Coffee House, and he bought stock in that jittery enterprise. The printer’s older brother Malcolm sold subscriptions up in Maine.

That Boston Evening Gazette evolved into the the Boston Intelligencer in August 1816. Burdick sold the business the following January and died on 30 May 1817, under Dr. John Collins Warren’s care. He was intestate but solvent, so his widow Lucretia could settle the estate and live for three more decades. She was interred in the Sprague family tomb in Boston’s Central Burying-Ground, shown above.

I imagine his wife Jane did a lot of the hosting since Benjamin remained Constable of the Town House Watch through 1774.

As the London government cracked down and war approached, the Burdicks moved out to Marblehead. Benjamin opened a “large, genteel, and commodious” inn opposite Jeremiah Lee’s mansion. Soon he was watching over auctions of captured goods and vessels. Later the inn hosted auctions of estates confiscated from absent Loyalists.

By 1786 Burdick had relocated to Danvers, at the Sign of the Flag, but that property was sold the next year. Jane was back in Boston when she died in 1791. I haven’t found a record of Benjamin’s death. (It doesn’t help that genealogists have intertwined him with a man of the same name from Westerly, Rhode Island.)

In 1778, the Boston merchant Samuel Phillips funded the opening of a new academy in Andover with Eliphalet Pearson as preceptor. The inaugural class of that school included Malcolm McNeil Burdick, born in Boston 1764—the Burdicks’ oldest son. (His first and middle name appeared with different spellings.) Malcolm was in his teens but for some reason listed as age ten in school records.

Later Malcolm M. Burdick went to sea, appearing in advertisements as master of the Minerva sailing from Baltimore to Liverpool in 1801 and of the John out of New York in 1807. By 1812 he had settled in Windham, Maine, where he advertised that someone else’s livestock had gotten onto his land.

Another of Benjamin and Jane Burdick’s sons, William, born in 1774, went into printing. In July 1795 he and Benjamin Sweetser cofounded a newspaper in Boston called the Courier. Soon that became The Courier, Boston Evening Gazette and Universal Advertiser. Burdick signed over his portion of the business to Sweetser in December, and it ceased publishing in March 1796 after a fire.

[ADDENDUM: From 1798 to 1800 William Burdick was the junior partner in publishing the Oriental Trumpet newspaper in Portland, Maine. He then returned to Boston.]

In 1809 William Burdick married Lucretia Sprague (1788–1849), daughter of Continental artillery veteran Samuel Sprague (1753–1844). According to her brother, the banker and poet Charles Sprague (1791–1895), their father was also part of the Boston Tea Party.

William Burdick reused the Boston Evening Gazette name for a new periodical in 1813. His printing office at Congress and State Streets was next to the Exchange Coffee House, and he bought stock in that jittery enterprise. The printer’s older brother Malcolm sold subscriptions up in Maine.

That Boston Evening Gazette evolved into the the Boston Intelligencer in August 1816. Burdick sold the business the following January and died on 30 May 1817, under Dr. John Collins Warren’s care. He was intestate but solvent, so his widow Lucretia could settle the estate and live for three more decades. She was interred in the Sprague family tomb in Boston’s Central Burying-Ground, shown above.

Saturday, December 20, 2025

“I can recollect something of their faces…”

As recounted yesterday, immediately after the Boston Massacre, town watchman Benjamin Burdick went up to the soldiers and examined their faces so he could identify them later.

That didn’t actually turn out to be helpful.

When he was called to testify at the soldiers’ trial in November, Burdick had this exchange:

However, multiple other witnesses agreed that Pvt. Montgomery was on the right end of the grenadiers’ arc (James Bailey, Jedediah Bass), and that the man in that position was the first to fire (Bailey, Bass, James Brewer, Thomas Wilkinson, Nathaniel Fosdick, Joseph Hiller). The watchman himself described the first shot coming from “the right hand man,” not the men closest to him. So the soldier Burdick spoke to wasn’t Montgomery, despite all his effort to memorize the men’s faces on King Street.

Burdick’s testimony does offer us some details about the soldiers in the courtroom. As defendants, those men were “dressed” differently from how they appeared on 5 March—differently enough for Burdick to say he could no longer recognize any of them with certainty. That suggests the soldiers were no longer wearing their full uniforms.

In addition, Montgomery wasn’t wearing a wig or hat since Burdick (who, incidentally, had been trained as a barber and peruke-maker) saw that he was “bald.”

That didn’t actually turn out to be helpful.

When he was called to testify at the soldiers’ trial in November, Burdick had this exchange:

Q. Did you see any of these prisoners in King street the night of the 5th of March?John Adams’s notes on this exchange echo some details:

A. Not that I can swear to as they are dressed. I can recollect something of their faces, but cannot swear to them.

When I came to King-street, I went immediately up to one of the soldiers, which I take to be that man who is bald on the head, (pointing to [Edward] Montgomery). I asked him if any of the soldiers were loaded, he said yes. I asked him if they were going to fire, he said yes, by the eternal God, and pushed at me with his bayonet, which I put by with what was in my hand.

Q. What was it?

A. A Highland broad sword.

I went up to one that I take to be the bald man but cant swear to any. I askd him if he intended to fire. Yes by the eternal God. I had a Cutlass or high Land broad sword in my Hand.In an earlier deposition Burdick said that the soldier he spoke to was “the fourth man from the corner, who stood in the gutter.”

However, multiple other witnesses agreed that Pvt. Montgomery was on the right end of the grenadiers’ arc (James Bailey, Jedediah Bass), and that the man in that position was the first to fire (Bailey, Bass, James Brewer, Thomas Wilkinson, Nathaniel Fosdick, Joseph Hiller). The watchman himself described the first shot coming from “the right hand man,” not the men closest to him. So the soldier Burdick spoke to wasn’t Montgomery, despite all his effort to memorize the men’s faces on King Street.

Burdick’s testimony does offer us some details about the soldiers in the courtroom. As defendants, those men were “dressed” differently from how they appeared on 5 March—differently enough for Burdick to say he could no longer recognize any of them with certainty. That suggests the soldiers were no longer wearing their full uniforms.

In addition, Montgomery wasn’t wearing a wig or hat since Burdick (who, incidentally, had been trained as a barber and peruke-maker) saw that he was “bald.”

Friday, December 19, 2025

“I wanted to see some faces that I might swear to”

For a new project I’ve been taking a deep dive into Benjamin Burdick’s accounts of the Boston Massacre.

Back in 2008 I pointed out that, while previous publications about the event didn’t make this clear, Burdick was a Constable of the Town House Watch. All his actions make sense when we consider that he was on King Street to keep the peace and enforce the law.

One of those actions was helping to carry away the bodies. As Burdick brought Dr. Joseph Gardner and David Bradlee to lift Crispus Attucks, the soldiers aimed their muskets again. Capt. Thomas Preston knocked the guns up, telling his men not to fire.

Burdick then boldly walked up to the soldiers. Here’s how he’s quoted describing that action in different sources.

Boston’s Short Narrative report, printing Burdick’s own deposition:

Burdick’s testimony at the soldiers’ trial, as taken down by John Hodgson:

TOMORROW: Burdick identifying individual soldiers?

Back in 2008 I pointed out that, while previous publications about the event didn’t make this clear, Burdick was a Constable of the Town House Watch. All his actions make sense when we consider that he was on King Street to keep the peace and enforce the law.

One of those actions was helping to carry away the bodies. As Burdick brought Dr. Joseph Gardner and David Bradlee to lift Crispus Attucks, the soldiers aimed their muskets again. Capt. Thomas Preston knocked the guns up, telling his men not to fire.

Burdick then boldly walked up to the soldiers. Here’s how he’s quoted describing that action in different sources.

Boston’s Short Narrative report, printing Burdick’s own deposition:

I then went close up to them, and addressing myself to the whole, told them I came to see some faces that I might be able to swear to another day—Capt. Preston, who was the officer, turned round and answered (in a melancholy tone) perhaps you may. After taking a view of each man’s face I left them.Prosecuting attorney Robert Treat Paine’s notes on how Burdick testified at Capt. Preston’s trial:

I said I wanted to see a face I should sware to, Prisoner said in a Melancholly tone perhaps you may.An anonymous spectator in the courtroom taking notes for Gov. Thomas Hutchinson:

After the firing I went up to the Soldiers and told them I wanted to see some faces that I might swear to them another day. The Centinel in a melancholy tone said perhaps Sir you may.(This observer moved Preston’s words into the mouth of the sentry, Pvt. Hugh White. Or the transcriber mistook “Captain” for “Centinel.”)

Burdick’s testimony at the soldiers’ trial, as taken down by John Hodgson:

I went to them to see if I could know their faces again; Capt. Preston looked out betwixt two of them, and spoke to me, which took off my attention from them.John Adams took notes on what Burdick said at the second trial, but not on that detail.

TOMORROW: Burdick identifying individual soldiers?

Thursday, December 18, 2025

“Promised on receiving a bribe, to let a person bring out £240”

Along with the other reports on life inside besieged Boston that I discussed yesterday, on 17 Dec 1775 Capt. Richard Dodge reported this dastardly deed:

That story soon got to printer Benjamin Edes, as reported in his next issue of the Boston Gazette on 25 December:

One of Capt. Dodge’s informants, a ship captain named Nowell, then went home to Newburyport and told the same story for the 22 December Essex Journal:

(Shown above: Two Portoguese Johannes coins from the mid-1700s, courtesy of BrianRxm.)

Morson Scotch menster took Bribe of A Sertain Genttelmen of 36/ Starling to Gett Out of Boston and 72/ to Let him Bring Out A trunk of £240 Pound in Cash Wich when he Had it in his Power sezd the Holl and Carreed it to Boston A Gain.In more familiar spelling, the Rev. John Morrison, a Presbyterian minister from Peterborough, New Hampshire, who had come to the siege lines as a chaplain and then defected to the British, charged a man more than £5 to slip out of Boston with cash, but then confiscated the cash.

That story soon got to printer Benjamin Edes, as reported in his next issue of the Boston Gazette on 25 December:

That one Morrison, who officiates as a Presbyterian minister, being appointed searcher of those people who were permitted to leave the town, promised on receiving a bribe, to let a person bring out £240 sterling in cash and plate: but afterwards basely deprived him of the whole of it:—That article was reprinted in the Pennsylvania Packet on 1 Jan 1776, and here on Boston 1775 in 2008.

One of Capt. Dodge’s informants, a ship captain named Nowell, then went home to Newburyport and told the same story for the 22 December Essex Journal:

That one Morrison a Scotch minister, was appointed to search the inhabitants upon their leaving the town, who received a bribe of two Johanneses to let a small trunk pass unmolested, yet notwithstanding his engagements, he opened the trunk and took out 2400 pounds in cash and a quantity of plate, which was all the trunk contained; what we suppose induced him to this, was, because the informer is intitled to one half of the plunder.But this time, the numbers got bigger.

(Shown above: Two Portoguese Johannes coins from the mid-1700s, courtesy of BrianRxm.)

Wednesday, December 17, 2025

Eight Runaway Men in a Boat from Boston

Capt. Richard Dodge was a Continental Army officer stationed in Chelsea during the second half of 1775. Like his regimental commander, Lt. Col. Loammi Baldwin, he sent periodic reports to Gen. George Washington’s headquarters about what he saw in Boston harbor.

On 16 December, Dodge reported some exciting news: “Last Eveing Eight men Runaway in a bote from Boston to our guard at the farry.”

Following recently enacted protocol, Dodge sent those men to a local health committee who “Clensed them by Smooking them” against the smallpox.

Six (or seven, according to the 25 December Boston Gazette) of those eight men were “masters of Vassels” captured by the Royal Navy and brought into Boston over the preceding months.

One, Capt. James Warden, had sailed for the Philadelphia merchant Thomas Mifflin and was anxious to renew their acquaintance now that Mifflin was the army’s quartermaster general. Naval Documents of the American Revolution reports that Warden was commanding the schooner Tryal on 22 August when it surrendered to H.M.S. Nautilus under Capt. John Collins.

The Essex Journal of Newburyport identified another of those ship’s captains as named Nowell, possibly Silas Nowell (who wouldn’t have been held that long). He came out with a copy of the Boston News-Letter, the only newspaper still being published in the town, and the news that Gen. John Burgoyne had sailed for England.

On 17 December, 250 years ago today, Dodge wrote out a précis of what those men told him about life inside Boston. The prices for food were high. One escapee reported that “he Dined with a man that Dined with Lord parsey a feu Day ago upon horse beaff.”

Firewood was even scarcer with winter coming on. Gen. William Howe had ordered the Old North Meeting-House and empty houses torn down for fuel. We also know Howe told London that he might have to order wharves torn up next.

Citing Capt. Nowell, the newspapers added that “all the drugs and medicines in the town have been seized for the use of the army.”

TOMORROW: Tales of the searcher.

On 16 December, Dodge reported some exciting news: “Last Eveing Eight men Runaway in a bote from Boston to our guard at the farry.”

Following recently enacted protocol, Dodge sent those men to a local health committee who “Clensed them by Smooking them” against the smallpox.

Six (or seven, according to the 25 December Boston Gazette) of those eight men were “masters of Vassels” captured by the Royal Navy and brought into Boston over the preceding months.

One, Capt. James Warden, had sailed for the Philadelphia merchant Thomas Mifflin and was anxious to renew their acquaintance now that Mifflin was the army’s quartermaster general. Naval Documents of the American Revolution reports that Warden was commanding the schooner Tryal on 22 August when it surrendered to H.M.S. Nautilus under Capt. John Collins.

The Essex Journal of Newburyport identified another of those ship’s captains as named Nowell, possibly Silas Nowell (who wouldn’t have been held that long). He came out with a copy of the Boston News-Letter, the only newspaper still being published in the town, and the news that Gen. John Burgoyne had sailed for England.

On 17 December, 250 years ago today, Dodge wrote out a précis of what those men told him about life inside Boston. The prices for food were high. One escapee reported that “he Dined with a man that Dined with Lord parsey a feu Day ago upon horse beaff.”

Firewood was even scarcer with winter coming on. Gen. William Howe had ordered the Old North Meeting-House and empty houses torn down for fuel. We also know Howe told London that he might have to order wharves torn up next.

Citing Capt. Nowell, the newspapers added that “all the drugs and medicines in the town have been seized for the use of the army.”

TOMORROW: Tales of the searcher.

Tuesday, December 16, 2025

Call for Papers on Eyewitness Accounts of the Revolution in the Mid-Atlantic

To mark the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Historic Trappe, the McNeil Center for Early American Studies, and Ursinus College will convene a symposium about “Experiencing Independence: Eyewitness Accounts of the American Revolution” on October 2–3, 2026.

This symposium will explore the diaries, journals, letters, and material culture of people in the mid-Atlantic region of America from 1760–1790.

The organizers say:

This symposium will explore the diaries, journals, letters, and material culture of people in the mid-Atlantic region of America from 1760–1790.

The organizers say:

We seek to convene panels that explore family dynamics in the midst of political upheaval, wartime experiences of soldiers and civilians, accounts from different religious perspectives, and new approaches to non-English sources on the American Revolution.Participants in “Experiencing Independence” will be able to tour Historic Trappe’s sites, including:

We invite papers from historians, museum curators, educators, conservators, tour guides, reenactors, and other experts who rely on these sources to interpret military engagements, domestic life, and political and cultural changes of this period. Scholars of all backgrounds, disciplines, and career stages are encouraged to submit proposals.

- the home of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg and his wife Mary (shown above), who moved in the week following the Declaration of Independence

- the home of his son, Frederick Muhlenberg, which will open to the public in 2026 after a twenty-five-year restoration

- the special exhibition “Window to Revolution: Pennsylvania Germans and the War for Independence” in the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies at the Dewees Tavern

Monday, December 15, 2025

The Northern Department’s Wagon Masters in 1778

On 21 Aug 1778, Morgan Lewis (1754–1844), deputy quartermaster general of the Northern Department of the Continental Army, wrote out a list of men working under him.

A copy of that document is now in Horatio Gates’s papers. It’s transcribed here as part of a New York State Museum web exhibit called “The People of Colonial Albany Lived Here.”

Lewis listed four men as wagon masters that summer, and Stefan Bielinski provided profiles of three of them:

August 1778 was well over two years after Gen. Philip Schuyler sent his wagon master out to recruit teams of horses for Col. Henry Knox. Nonetheless, it would be worth looking at his papers from 1775 to see if he worked with any of these three men. Documents show that Schuyler interacted with other members of the Winne and Yates families after 1778, but of course Albany was a small society and Schuyler had lots of business.

As for Samuel Bond, Gen. George Washington’s general orders for 9 Sept 1778 state that at a court martial on 31 August (or ten days after Lewis made his list):

Deputy quartermaster general Morgan Lewis went on to become the third elected governor of New York, as shown above.

A copy of that document is now in Horatio Gates’s papers. It’s transcribed here as part of a New York State Museum web exhibit called “The People of Colonial Albany Lived Here.”

Lewis listed four men as wagon masters that summer, and Stefan Bielinski provided profiles of three of them:

- Jellis Winne (1732–1804).

- Frans Winne (1734–1797?).

- Samuel Bond.

- Christopher A. Yates (1739–1809).

August 1778 was well over two years after Gen. Philip Schuyler sent his wagon master out to recruit teams of horses for Col. Henry Knox. Nonetheless, it would be worth looking at his papers from 1775 to see if he worked with any of these three men. Documents show that Schuyler interacted with other members of the Winne and Yates families after 1778, but of course Albany was a small society and Schuyler had lots of business.

As for Samuel Bond, Gen. George Washington’s general orders for 9 Sept 1778 state that at a court martial on 31 August (or ten days after Lewis made his list):

Samuel Bond Assistant Waggon Master was tried for 1st “Picking a Lock; breaking into a public store and taking from thence rum and Candles” which he appropriated to his own use, found guilty of the charges exhibited against him and sentenced to receive fifty lashes and to return to the Regiment from which he was taken.Bond thus appears to have been a regular soldier drafted to manage wagons, and then sent back into the ranks.

The General remits the stripes & orders said Bond to return to the Regiment from which he was taken.

Deputy quartermaster general Morgan Lewis went on to become the third elected governor of New York, as shown above.

Sunday, December 14, 2025

“I Enquired for the waggon master”

On 16 May 1776, Gen. John Sullivan was at Albany, New York, trying to organize the remnants of the Continental Army’s invasion of Canada.

On 16 May 1776, Gen. John Sullivan was at Albany, New York, trying to organize the remnants of the Continental Army’s invasion of Canada. He sent a letter to Gen. George Washington complaining of the Northern Department’s wagon master, among other things:

Early on the 15 Inst. to my Surprize I found three hundred Barrels (which I had Sent forward) Lying on the Beach without any teams to Carry them to Still water about twelve miles furtherTwo days later Sullivan sent off another complaint about the wagon drivers:

I Enquired for the waggon master & was Informed he was at his own House About Six miles off

I Immediately wrote him of the Necessity of his Exerting himself at this time

I found at Still water a Number of Barrells of Pork that the Waggoners had Tap[p]ed & Drawn off the pickle to Lighten their Teams. This pork must Enevetably be Ruin’d before it can reach Canada,Washington passed on word of those complaints to Schuyler, who responded a month later:

as Genl [Philip] Schuyler was Absent I Order’d the Commissary not to Receive any Such from the Waggoners & the Commissary at half moon not to receive out of the Boats any or Deliver out such to the Waggoners.

I order’d the Waggoners not to Receive any such as it would Eventually be thrown on their hands I then Directed the Commissary here not to Send any Barrels forwards that had lost the Pickle which would be only taking up Batteaus & Waggons to Cary Provisions which when brought to Canada Could not be Eaten.

By this Step I hope to prevent any further fraud in the Waggoners who (it is said) Learnt this piece of Skill in the Last War, for which Some of them were well flogged, and I hope Some of them may Share the Same fate—again.

As to the Waggon master he is an Industrious Active and I believe an honest Man, But It is not in his Power, nor any Mans whatsoever to procure Waggons at all Times & at that Time It was peculiarly difficult both on Account of the Scarcity of Forrage the Badness of the Roads and the extravagant Abuses the Waggoners had met with from some of the Troops that preceded General Sullivan’s Brigade.Neither general named the wagon master, which might reflect how he wielded authority over the teamsters but wasn’t at the level of a gentlemen. Their letters do offer some clues about the man: He had his own house about six miles from where Sullivan was in Albany. He was literate. He was independent.

Now that man in May 1776 wasn’t necessarily the same official whom Schuyler oversaw in December 1775. Nonetheless, he was clearly not one of Schuyler’s slaves.

TOMORROW: Names at last.

Saturday, December 13, 2025

Was Gen. Schuyler’s Wagon Master One of His Enslaved Workers?

As quoted yesterday, on 29 Dec 1775 Col. Henry Knox wrote that Gen. Philip Schuyler “sent out his Waggon Master & other people to all parts of the Country” to hire teams of horses for transporting heavy ordnance to Springfield.

Back in 2016 Ian Mumpton at the Schuyler Mansion wrote:

I wouldn’t be surprised if Gen. Schuyler assigned some of his enslaved wagon drivers to the operation moving cannon toward Boston (and collected the same pay he was offering to other farmers for himself).

However, I’m not convinced that one of those men could have been Schuyler’s “Waggon Master.” That was an official designation within the Continental Army’s quartermaster department. On 9 August, Gen. George Washington appointed John Goddard of Brookline “Waggon Master General to the Army of the Twelve United Colonies.” (That count included Georgia but not Delaware, still officially a subset of Pennsylvania.)

In the fall of 1775 Schuyler had overseen preparations for Gen. Richard Montgomery’s invasion of Canada, an operation that probably required a convoy of wagons and thus an official to oversee them.

And that’s a crucial aspect of the job of wagon master. It required more than driving a wagon—indeed, the wagon master might not do any actual driving at all. The job involved making deals on behalf of the Continental Army with a large number of independent contractors and then overseeing a force of teamsters. The word “master” was even in the name. Did any enslaved man, however skilled, have the legal standing and social authority to do that job in 1775?

TOMORROW: Glimpses of Schuyler’s wagon master in spring 1776.

Back in 2016 Ian Mumpton at the Schuyler Mansion wrote:

It is unclear who the “Waggon Master” refers to, but as mentioned in a previous article, many of the men enslaved by the Schuyler family were skilled at driving carts and sleds. As there is no surviving record of Schuyler hiring a wagon master, it is likely that this person was one of the enslaved servants, possibly Lisbon or a man named Lewis who, five months later, was lent to Benjamin Franklin as a driver for a trip from the Schuyler’s home to New York City.That previous article, also posted by Mumpton, analyzed a 1771 document which mentioned enslaved workers and said:

Lisbon and Dick are both mentioned in other Schuyler documents as carters or wagoners, conveying goods and people for the Schuyler family. Lisbon in particular is mentioned in at least four other sources, always in regards to his driving goods back and forth between Albany and Saratoga. These men’s ability to drive carts and sleds was a large part of their value to the Schuylers, as this was a specialized skill-set that involved being able to work with draft animals, manage tack and harness, and maintain the carts and sleds in their charge.A comment noted another wagon driver named Anthony, Tony, or Tone.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Gen. Schuyler assigned some of his enslaved wagon drivers to the operation moving cannon toward Boston (and collected the same pay he was offering to other farmers for himself).

However, I’m not convinced that one of those men could have been Schuyler’s “Waggon Master.” That was an official designation within the Continental Army’s quartermaster department. On 9 August, Gen. George Washington appointed John Goddard of Brookline “Waggon Master General to the Army of the Twelve United Colonies.” (That count included Georgia but not Delaware, still officially a subset of Pennsylvania.)

In the fall of 1775 Schuyler had overseen preparations for Gen. Richard Montgomery’s invasion of Canada, an operation that probably required a convoy of wagons and thus an official to oversee them.

And that’s a crucial aspect of the job of wagon master. It required more than driving a wagon—indeed, the wagon master might not do any actual driving at all. The job involved making deals on behalf of the Continental Army with a large number of independent contractors and then overseeing a force of teamsters. The word “master” was even in the name. Did any enslaved man, however skilled, have the legal standing and social authority to do that job in 1775?

TOMORROW: Glimpses of Schuyler’s wagon master in spring 1776.

Friday, December 12, 2025

“After a considerable degree of conversation”

On Christmas 1775, Col. Henry Knox was making his way on horseback to Gen. Philip Schuyler’s mansion in Albany, New York.

Knox has just called off his deal with George Palmer of Stillwater to supply eighty pair of oxen to transport heavy cannon into Massachusetts.

Palmer was in his late fifties. Born in Connecticut, he had bought mills and other real estate in Stillwater in 1764 and become a big man in that town. He didn’t like being dismissed, as shown by the letter I quoted yesterday.

Since we have only one side of the correspondence, we don’t know if Knox had revealed that he’d canceled the deal on a direct order from Gen. Schuyler, who insisted he’d started making his own arrangements for moving the cannon.

Schuyler was in his mid-forties, scion of a family of Dutch landowners in Albany. He was a big man in the whole colony. He’d been elected to the Second Continental Congress and then appointed a general of the Continental Army in charge of the Northern Department.

In between those two local bigwigs was Knox, a twenty-five-year-old from Boston who hadn’t yet received his official commission as colonel. He was following orders direct from Gen. George Washington, but that mentor was very far away.

On the afternoon of 26 December, Knox reached Schuyler’s house. Evidently he persuaded the general to at least talk with Palmer. The next day Knox wrote in his journal: “Sent off for Mr Palmer to Come immediately down to Albany.”

On 28 December Knox recorded the result of that meeting:

Authors describe Knox scrapping his initial plan to use Palmer’s oxen as purely a matter of cost. That makes the situation seem entirely reasonable, especially on the part of the men commemorated with statues—Schuyler and Knox. But Schuyler had told Knox to dismiss Palmer more than a week before this sit-down, before he knew anything about prices.

That suggests Schuyler made his decision on something besides 5s.3d per day. He and Palmer might have been rivals for influence in the county. He might have assumed Palmer wouldn’t offer the best price. He might have felt he’d sunk too much money into his own preparations to stop now. The general might simply have wanted more control.

Whatever his motivation, on 29 December Schuyler sent his wagon master and other agents “to all parts of the County to immediately send up their slays with horses,” as Knox wrote. The price would be “12/. P[er] day for each pair of horses or £7. P[er] Ton for 62 miles.” At the end of the year the wagon master brought back a list of 124 teams. That number of horses would cost £74.8s. per day.

In contrast, Palmer had offered 80 yoke of oxen. Knox wrote that he ultimately quoted 24s. per day “for 2 Yoke of Oxen.” If that’s correct, using Palmer’s oxen would have cost £48 per day, considerably less than Schuyler’s arrangement. However, if Knox really meant that price to apply to each yoke of two oxen (the usual way of calculating), then Palmer was indeed asking for more than Schuyler.

There might well have been other costs and factors involved, such as the number of teamsters needed or how quickly the animals and equipment could be assembled. But whatever the details, it seems clear that Schuyler was making the decisions at this point, not Knox.

Indeed, Knox confided some worries about the final arrangement in his journal, meant for himself and perhaps for showing Gen. Washington later. On 31 December he wrote about the “Slays which I’m afraid are not Strong enough for the heavy Cannon If I can Judge from the sample Shewn me by Genl Schuyler.”

Nonetheless, those sleighs and those horses were what he had to work with.

TOMORROW: The wagon master.

Knox has just called off his deal with George Palmer of Stillwater to supply eighty pair of oxen to transport heavy cannon into Massachusetts.

Palmer was in his late fifties. Born in Connecticut, he had bought mills and other real estate in Stillwater in 1764 and become a big man in that town. He didn’t like being dismissed, as shown by the letter I quoted yesterday.

Since we have only one side of the correspondence, we don’t know if Knox had revealed that he’d canceled the deal on a direct order from Gen. Schuyler, who insisted he’d started making his own arrangements for moving the cannon.

Schuyler was in his mid-forties, scion of a family of Dutch landowners in Albany. He was a big man in the whole colony. He’d been elected to the Second Continental Congress and then appointed a general of the Continental Army in charge of the Northern Department.

In between those two local bigwigs was Knox, a twenty-five-year-old from Boston who hadn’t yet received his official commission as colonel. He was following orders direct from Gen. George Washington, but that mentor was very far away.

On the afternoon of 26 December, Knox reached Schuyler’s house. Evidently he persuaded the general to at least talk with Palmer. The next day Knox wrote in his journal: “Sent off for Mr Palmer to Come immediately down to Albany.”

On 28 December Knox recorded the result of that meeting:

Mr Palmer Came Down & after a considerable degree of conversation between him & General Schuyler about the price the Genl Offering 18/9. & Palmer asking 24/. P[er] day for 2 Yoke of Oxen the treaty broke off abrubtly & Mr Palmer was dismiss’dIt seems clear from the way Knox described that long conversation as between Palmer and Schuyler that he was left out—perhaps he even wanted to be left out. We don’t know what price he had offered Palmer and thus how that fit into this conversation. Did Schuyler bargain Palmer down, or did Palmer insist on sticking to the original deal?

Authors describe Knox scrapping his initial plan to use Palmer’s oxen as purely a matter of cost. That makes the situation seem entirely reasonable, especially on the part of the men commemorated with statues—Schuyler and Knox. But Schuyler had told Knox to dismiss Palmer more than a week before this sit-down, before he knew anything about prices.

That suggests Schuyler made his decision on something besides 5s.3d per day. He and Palmer might have been rivals for influence in the county. He might have assumed Palmer wouldn’t offer the best price. He might have felt he’d sunk too much money into his own preparations to stop now. The general might simply have wanted more control.

Whatever his motivation, on 29 December Schuyler sent his wagon master and other agents “to all parts of the County to immediately send up their slays with horses,” as Knox wrote. The price would be “12/. P[er] day for each pair of horses or £7. P[er] Ton for 62 miles.” At the end of the year the wagon master brought back a list of 124 teams. That number of horses would cost £74.8s. per day.