Usually I get intrigued, think about possible answers, often type up something to edit down to the requisite length. And then other things land on top of the task pile and I end up never sending in an answer.

But I was able to muster a reply to the latest challenge for contributors: “an artifact from the 1765–1805 era known to have existed well into the nineteenth century, that has since been stolen or gone missing.”

The various answers include one painting and three medals stolen in the second half of the twentieth century, several items of clothing that have probably been tossed out or disintegrated, and an entire financial archive.

Plus, Elias Boudinot’s handwritten memoir (which was, thankfully, transcribed and published before disappearing from archive shelves), two cannon captured at Saratoga and recaptured one war later, and possibly an entire Hessian colonel.

Another example occurs to me now, but I’m not sure it meets the criterion of having “existed well into the nineteenth century.”

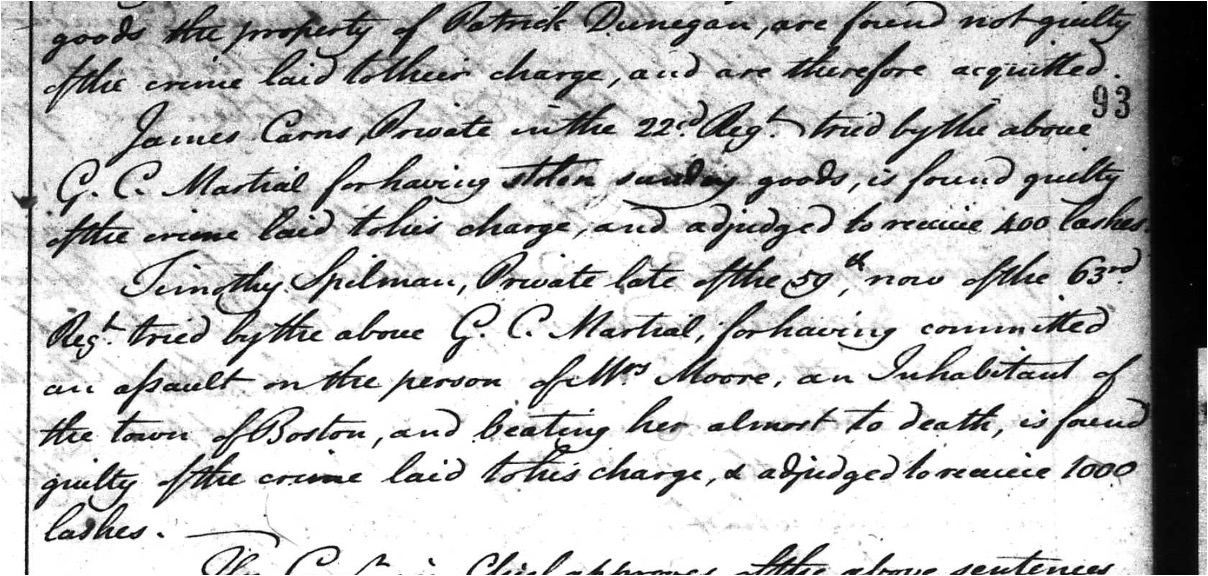

On 16 Feb 1836, the printer Peter Edes, son of Benjamin Edes of the Boston Gazette and the Loyall Nine, wrote to his grandson:

It is a little surprising that the names of the tea-party were never made public: my father, I believe, was the only person who had a list of them, and he always kept it locked up in his desk while living. After his death Benj. Austin called upon my mother, and told her there was in his possession when living some very important papers belonging to the Whig party, which he wished not to be publicly known, and asked her to let him have the keys of the desk to examine it, which she delivered to him; he then examined it, and took out several papers, among which it was supposed he took away the list of the names of the tea-party, and they have not been known since.Benjamin Edes died in 1803, his widow Martha in 1809, and this encounter would have happened between those dates, probably earlier. There were two politically active Benjamin Austins in Boston, father and son; the first died in 1806, the second in 1820.

Did Benjamin Edes really keep such a list, and why? Did Benjamin Austin do away with that document? If so, did he act because of the names that were on it or the names that weren’t on it?

%2C_Nova_Scotia.png/250px-James_Moody_(1744-1809)%2C_Nova_Scotia.png)