Some of the last historical events I attended in person were the Sestercentennial commemorations of the Boston Massacre at the Old South Meeting House and the Old State House—now Revolutionary Spaces.

At the time, the Old State House museum was opening a new exhibit called “Reflecting Attucks.” I was looking forward to visiting it as soon as my schedule cleared. And then the pandemic shut us all down.

Revolutionary Spaces has now reopened for limited visitation, Thursdays through Sundays, 10:00 A.M. to 4:00 P.M. The organization has also launched a digital companion to “Reflecting Attucks” using programming and digital content to offer a deeper look at the life and legacy of Crispus Attucks.

Upcoming online programs for the public include these panel discussions featuring historians and other scholars.

Wednesday, 16 September, 4:00 P.M.

“Attucks: A Man of Many Worlds”

A lively online discussion about Attucks’s Afro-Indian community and the experiences that might have informed his thinking and brought him out to King Street.

Tuesday, 22 September, 4:00 P.M.

“Liberty and Sovereignty in 18th-Century New England”

This discussion delves into the political and philosophical conversations about liberty and sovereignty that evolved around the time of the Boston Massacre.

Tuesday, 29 September, 4:00 P.M.

“Imagining Attucks”

The panelists explore how Attucks has been interpreted through the years and grapple with the challenges that come with portraying Attucks.

Tuesday, 20 October, 4:00 P.M.

“Demanding Freedom: Attucks and the Abolition Movement”

A group reflection on how nineteenth-century abolitionists revived Crispus Attucks’s memory in their fight to end slavery.

In addition, there are three online talks for Revolutionary Spaces members starting on 9 September.

History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

▼

Monday, August 31, 2020

Sunday, August 30, 2020

“A Day which ought to be forever remembered in America”

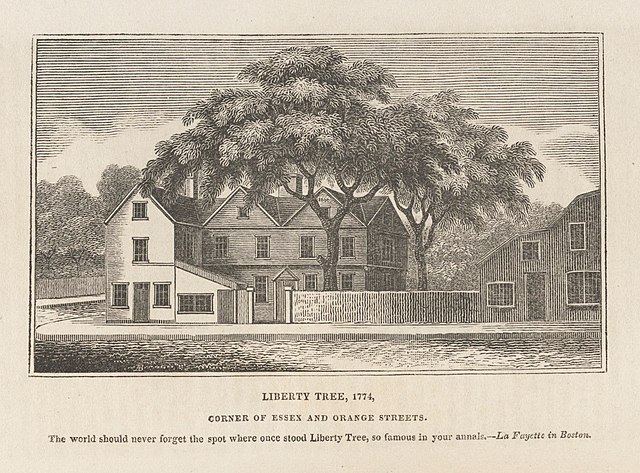

Earlier this month I posited that the American Revolution began on 14 Aug 1765 with the earliest public protest against the Stamp Act, the first step in turning a debate among legislatures into a continent-wide mass movement.

After the riots on 26 August, culminating in the destruction of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house, the Boston Whigs had a strong motive to focus public memory on that first date so they could disavow what happened on the second.

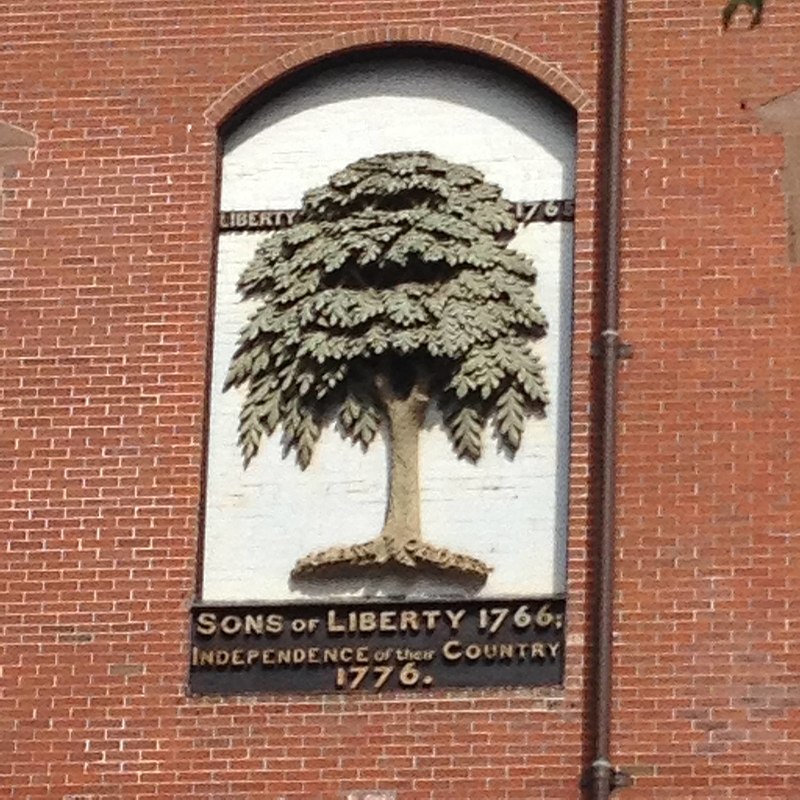

Those Sons of Liberty decorated Liberty Tree in the South End with a plaque and that famous name. [Don’t think about what happened in the North End!] They held banquets on the anniversary of the first protest. [Don’t remember the second!] They kept the ritual of hanging political enemies in effigy, but no houses were damaged as badly as Hutchinson’s before the outbreak of war.

On 19 Aug 1771, the Boston Gazette published a front-page article signed “Candidus,” which politically minded Bostonians recognized to be Samuel Adams. He said:

In 1771, however, the town of Boston began to make a bigger deal of the 5th of March, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Then at the end of the Revolutionary War, the town switched its annual oration to the 4th of July, a date with undoubted national significance.

In the early 1800s retired President John Adams helped to shape the memory of the early Revolution by sharing recollections in letters and by encouraging William Tudor, Jr., to write a biography of James Otis, Jr. As I discussed way back here, Adams was responding to William Wirt’s biography of Patrick Henry, which credited a Virginian with kicking off the Stamp Act protest movement.

And in an important way, that’s what Patrick Henry did in the Virginia House of Burgesses. And exaggerated reports of Patrick Henry’s proposals did even more. Those newspaper reports probably emboldened the Loyall Nine in Boston.

Adams, who called himself “jealous, very jealous, of the honour of Massachusetts,” wanted Americans to see his home state as a leader in the resistance to London, not just a close follower. He pointed to Otis’s arguments in the 1761 writs of assistance case in these terms: “Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.” That pushed the start of the American Revolution back.

I’m not won over by Adams’s position. Otis’s argument was unsuccessful and got limited press coverage outside of Massachusetts, where the legal decision didn’t apply anyway. Like Henry’s resolutions, the writs of assistance case was a protest from upper-class men inside exclusive chambers working through official channels. It wasn’t revolutionary.

After the riots on 26 August, culminating in the destruction of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house, the Boston Whigs had a strong motive to focus public memory on that first date so they could disavow what happened on the second.

Those Sons of Liberty decorated Liberty Tree in the South End with a plaque and that famous name. [Don’t think about what happened in the North End!] They held banquets on the anniversary of the first protest. [Don’t remember the second!] They kept the ritual of hanging political enemies in effigy, but no houses were damaged as badly as Hutchinson’s before the outbreak of war.

On 19 Aug 1771, the Boston Gazette published a front-page article signed “Candidus,” which politically minded Bostonians recognized to be Samuel Adams. He said:

The Sons of Liberty on the 14th of August 1765, a Day which ought to be forever remembered in America, animated with a zeal for their country then upon the brink of destruction, and resolved, at once to save her, or like Samson, to perish in the ruins, exerted themselves with such distinguished vigor, as made the house of Dagon to shake from its very foundation; and the hopes of the lords of the Philistines even while their hearts were merry, and when they were anticipating the joy of plundering this continent, were at that very time buried in the pit they had digged.Basically my argument about the significance of that date is the same, with fewer scriptural allusions.

The People shouted; and their shout was heard to the distant end of this Continent. In each Colony they deliberated and resolved, and every Stampman trembled; and swore by his Maker, that he would never execute a commission which he had so infamously received.

In 1771, however, the town of Boston began to make a bigger deal of the 5th of March, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Then at the end of the Revolutionary War, the town switched its annual oration to the 4th of July, a date with undoubted national significance.

In the early 1800s retired President John Adams helped to shape the memory of the early Revolution by sharing recollections in letters and by encouraging William Tudor, Jr., to write a biography of James Otis, Jr. As I discussed way back here, Adams was responding to William Wirt’s biography of Patrick Henry, which credited a Virginian with kicking off the Stamp Act protest movement.

And in an important way, that’s what Patrick Henry did in the Virginia House of Burgesses. And exaggerated reports of Patrick Henry’s proposals did even more. Those newspaper reports probably emboldened the Loyall Nine in Boston.

Adams, who called himself “jealous, very jealous, of the honour of Massachusetts,” wanted Americans to see his home state as a leader in the resistance to London, not just a close follower. He pointed to Otis’s arguments in the 1761 writs of assistance case in these terms: “Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.” That pushed the start of the American Revolution back.

I’m not won over by Adams’s position. Otis’s argument was unsuccessful and got limited press coverage outside of Massachusetts, where the legal decision didn’t apply anyway. Like Henry’s resolutions, the writs of assistance case was a protest from upper-class men inside exclusive chambers working through official channels. It wasn’t revolutionary.

Saturday, August 29, 2020

“Would it not be best to destroy this”

I already quoted the Rev. Jonathan Mayhew’s letter to Thomas Hutchinson after a mob ransacked the lieutenant governor‘s house.

At the end, after insisting he didn’t countenance violence, Mayhew asked Hutchinson “not to divulge what I now write, so that it may come to the knowledge of those enraged people.” The minister feared that knowing he’d disavowed the crowd’s action “might probably bring their heavy vengeance upon myself.”

Mayhew wasn’t the only Bostonian nervous about being known to support Lt. Gov. Hutchinson at this moment. On 28 Aug 1765, the elderly merchant, longtime Council member, and Old South deacon John Osborne (1688-1768) wrote to Hutchinson:

Another striking detail about Osborne’s worry is that Hutchinson didn’t act on it. He kept that letter, which is how it could be part of the collection being published by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Even at a low point, Hutchinson had the instincts of a historian to preserve documents.

At the end, after insisting he didn’t countenance violence, Mayhew asked Hutchinson “not to divulge what I now write, so that it may come to the knowledge of those enraged people.” The minister feared that knowing he’d disavowed the crowd’s action “might probably bring their heavy vengeance upon myself.”

Mayhew wasn’t the only Bostonian nervous about being known to support Lt. Gov. Hutchinson at this moment. On 28 Aug 1765, the elderly merchant, longtime Council member, and Old South deacon John Osborne (1688-1768) wrote to Hutchinson:

My heart is distres’d and bleeds for you on account of the abominable wicked treatment you & yours have meet with. I know not well what to say, how to begin nor where to Leav of . . .But Osborne finished his own letter with this postscript:

When I consider one of the best, honest, most usefull members of the House Vilely abused—& that without the Least provocation & this done among a Proffesing people Heaven Looks down with abhorance & I fear this people with its Resentment as well from above & from home. Surely the Government there canot Set Still and overlook, some hereby allready speak with concern what could be the concequence—& concern for our Charter privilidges &c. For my part shall nothing only cut a better Life. Tis no matter & truley I dont know whether these things wont finally finish.

P.S. I trust my Letter will not be so expos’d as to bring me & the old under the Rabels Resentment &c.It’s striking that Osborne worried about being seen as the lieutenant governor’s ally given that he had married Hutchinson’s widowed mother in 1745. Though Sarah (Foster Hutchinson) Osborne was no longer alive, Osborne was still the lieutenant governor’s stepfather. I think people would have assumed there might be some sympathy between them.

Would it not be best to destroy this.

Another striking detail about Osborne’s worry is that Hutchinson didn’t act on it. He kept that letter, which is how it could be part of the collection being published by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Even at a low point, Hutchinson had the instincts of a historian to preserve documents.

Friday, August 28, 2020

“It was a very unfortunate time to preach a sermon”

The Rev. Jonathan Mayhew insisted that, even though his sermon on 25 Aug 1765 decried the Stamp Act, Bostonians couldn’t have taken that as encouragement to riot against royal officials.

But crowds did riot the following night, and in particular they ransacked the house of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson.

At least one member of Mayhew’s own congregation was upset at him: the wealthy merchant Richard Clarke (shown here in a painting made about a decade later by his son-in-law, John Singleton Copley). Clarke decided to leave Mayhew’s church.

On 3 September, the minister wrote to the merchant in a last-ditch effort to patch things up. This long letter, published in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register in 1892, reveals that Mayhew, while still justifying what he had preached, had second thoughts about his sermon.

The problem had started, Mayhew said, with people urging him to preach about the Stamp Act.

Nevertheless, Mayhew lamented, people misunderstood him!

On Sunday, 1 September, Mayhew preached another sermon to condemn the riot—and he said he got criticized for that, too.

The main point of Mayhew’s letter, though, was his acknowledgment that he hadn’t anticipated how people would respond to his sermon and would have done things differently if he’d known:

Clarke must have shown Mayhew’s letter around because in his Massachusetts history Thomas Hutchinson wrote:

In the end, Hutchinson and his circle felt that Mayhew recognized his words had been dangerous and hoped that he’d be an example to other Whig leaders to tone down their rhetoric. The town’s politicians seem to have maintained the same talk of British liberties in danger, but they tried to exercise more control over popular demonstrations—enshrining Liberty Tree, remaking Pope Night that year, and loudly disavowing protests that went too far.

But crowds did riot the following night, and in particular they ransacked the house of Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson.

At least one member of Mayhew’s own congregation was upset at him: the wealthy merchant Richard Clarke (shown here in a painting made about a decade later by his son-in-law, John Singleton Copley). Clarke decided to leave Mayhew’s church.

On 3 September, the minister wrote to the merchant in a last-ditch effort to patch things up. This long letter, published in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register in 1892, reveals that Mayhew, while still justifying what he had preached, had second thoughts about his sermon.

The problem had started, Mayhew said, with people urging him to preach about the Stamp Act.

I had in company, before, often heard the ministers of this town in general blamed for their silence in the cause of liberty, at a time when it was almost universally supposed, as it still is, that our common liberties and rights, as British subjects, were in the most imminent danger. They were called cowards, and the like. And I had myself, for weeks, nay, for months before Aug. 25, been solicited by different persons to preach upon that subject, as one who was a known friend to liberty; and was in some measure reflected upon, as not having that good cause duly at heart, at this important crisis. This was a reproach, which I knew not well how to bear…Still, the minister insisted that his sermon cautioned against violence.

But certain I am, that no person could, without abusing & perverting it, take encouragement from it to go to mobbing, or to commit such abominable outrages as were lately committed, in defiance of the laws of God and man. I did, in the most formal, express manner, discountenance everything of that kind.Mayhew quoted several sentences from his sermon (as recreated from his notes) to reinforce that point. In particular, he stated that, contrary to what Hutchinson claimed, he had preached about the whole Biblical verse, which included the warning “use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh.”

Nevertheless, Mayhew lamented, people misunderstood him!

But as I found that some persons besides yourself had, thro’ mistake, and others through malice, represented my discourse in that odious light; and some, for their own ends, seemed disposed to make such a use of it as was remote from my thoughts, yea, as I had most expressly & formally guarded against; I thought it a duty incumbent upon me to exculpate myself in the most open & solemn manner.Days after the riot, the minister visited Clarke’s house and asked for advice “about putting something which I had written, in the public prints, relating to that very unhappy Affair.” Clarke declined to help with that newspaper essay, and I don’t think it ever appeared.

On Sunday, 1 September, Mayhew preached another sermon to condemn the riot—and he said he got criticized for that, too.

This I did the last Lord’s day, as probably you have heard; and did it so effectually, that I understand many persons are now highly displeased with me, as if I were a favourer of the stamp-act; of which I have still, however, the same opinion that I ever had, as a great grievance; in opposition to which, it is incumbent upon us to do everything in our power, within such restrictions as I had mentioned in my first discourse referred to.That seems rather prescient, doesn’t it?

I still love liberty as much as ever; but have apprehensions of the greatest inconveniences likely to follow on a forceable, violent opposition to an act of parliament; which I consider, in some sort, as proclaiming war against Great Britain. These are the Sentiments of my soul, which I more particularly declared the last Lord’s day, in the fear of God, and with the deepest concern for the welfare of my country, and all the British Colonies, at this most alarming Crisis which they have ever known, whether they do or do not submit to said act. What the end of these things will be, God only knows.

The main point of Mayhew’s letter, though, was his acknowledgment that he hadn’t anticipated how people would respond to his sermon and would have done things differently if he’d known:

I readily acknowledge, what I was not so well aware of before, that it was a very unfortunate time to preach a sermon, the chief aim of which was to show the importance of Liberty, when people were before so generally apprehensive of the danger of losing it. They certainly needed rather to be moderated and pacified, than the contrary: And I would freely give all that I have in the world, rather than have preached that sermon; tho’ I am well assured, it was very generally liked and commended by the hearers at the time of it.Judge Peter Oliver later wrote that the minister had “felt some severe Girds of what is vulgarly called Conscience; but he found, too late, that his Words were too hard of Digestion to be ate.”

Clarke must have shown Mayhew’s letter around because in his Massachusetts history Thomas Hutchinson wrote:

Dr. Mayhew, the preacher, in a letter to the lieutenant-governor, a few days after, expressed the greatest concern, nothing being further from his thoughts than such an effect; and declared, that, if the loss of his whole estate could recall the sermon, he would willingly part with it.In fact, Mayhew’s letter to the lieutenant governor (quoted yesterday) said, “I had rather lose my hand, than be an encourager of such outrages as were committed last night”—still insisting he hadn’t encouraged any. Hutchinson must have gotten the two expressions of regret amalgamated in his mind.

In the end, Hutchinson and his circle felt that Mayhew recognized his words had been dangerous and hoped that he’d be an example to other Whig leaders to tone down their rhetoric. The town’s politicians seem to have maintained the same talk of British liberties in danger, but they tried to exercise more control over popular demonstrations—enshrining Liberty Tree, remaking Pope Night that year, and loudly disavowing protests that went too far.

Thursday, August 27, 2020

“As if I approved of such proceedings”

On Tuesday, 27 August, the day after a mob destroyed Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house, some people blamed the Rev. Jonathan Mayhew’s latest sermon.

In his history of Massachusetts, Hutchinson wrote the sermon had implied “approbation of the prevailing irregularities.” Without naming his source, he said:

That view of events wiped out the need to consider ordinary people’s common grievances and their lack of other ways to express themselves politically. It reduced a complex situation, in which many Bostonians had resented Hutchinson for years and the town’s ministers carried a lot of weight, into a simple picture of a misguided puppeteer and puppets.

Hutchinson and his circle weren’t the only people who suspected Mayhew’s sermon might bear some responsibility for the riot. Mayhew himself got worried, if only because people were blaming him. On 27 August, he struggled over a letter to the lieutenant governor, now transcribed in the Colonial Society of Massachusetts’s Hutchinson Letters:

But was Mayhew protesting too much? Did he worry that his sermon had gone too far?

TOMORROW: Another sermon, and another letter.

In his history of Massachusetts, Hutchinson wrote the sermon had implied “approbation of the prevailing irregularities.” Without naming his source, he said:

One who had a chief hand in the outrages which soon followed, declared, when he was in prison, that he was excited to them by this sermon, and that he thought he was doing God service.That way of understanding the attack on Hutchinson’s mansion fit the Loyalist worldview: an influential and irresponsible upper-class leader, carried away by ideological enthusiasm or private resentment, riled up the mob, who then unthinkingly attacked an innocent, rational upper-class leader.

That view of events wiped out the need to consider ordinary people’s common grievances and their lack of other ways to express themselves politically. It reduced a complex situation, in which many Bostonians had resented Hutchinson for years and the town’s ministers carried a lot of weight, into a simple picture of a misguided puppeteer and puppets.

Hutchinson and his circle weren’t the only people who suspected Mayhew’s sermon might bear some responsibility for the riot. Mayhew himself got worried, if only because people were blaming him. On 27 August, he struggled over a letter to the lieutenant governor, now transcribed in the Colonial Society of Massachusetts’s Hutchinson Letters:

Honored Sir,Mayhew’s description of the situation fit the Whiggish worldview: he had delivered perfectly justified remarks about political and religious liberty, but his “numerous and causeless enemies” seized on a sort of trouble he’d never encouraged and indeed condemned to make him look bad.

I take the freedom to write you these few lines by way of condolence, on account of the almost unparalell’d outrages committed at your house the last evening, and the great Damage which I understand you have suffered thereby. God is my witness, that from the bottom of my heart I detest these proceedings; and that I am sincerely grieved for them, and have a deep sympathy with you and your distressed family on this occasion.

I the rather write to You in this manner, Sir, because I understand that some of my numerous and causeless enemies have expressed them selves to day, as if I approved of these doings, and had indeed encouraged them in a Sermon which I preached the last Lord’s day on Gal. 5. 12, 13. This I absolutely deny.

I did indeed express my self strongly in favor of civil & religious liberty, as I hope I shall ever continue to do; and spoke of the late Stamp Act as a grievance, likely to prove detrimental in a high degree, both to the Colonies, and to the Mother Country; which, I believe, is the sense of almost every person of understanding in the Plantations; and, particularly, I have heard your Honor speak to the same Purpose.

But then, as my text led me to do, I cautioned my Hearers very particularly against the abuses of liberty; and intimated my hopes, that no persons among our selves had encouraged the bringing of such a burden on their country, notwithstanding it had been strongly suspected.

Let me add, that when in private company I have often heard your Honor spoken of as one, who was supposed to have been an encourager of the Act aforesaid, I have as often taken the Liberty to say, I had heard you express your self in a manner that strongly implied the contrary; which I did with a view to remove those prejudices which I perceived some persons had against you in that respect. And, in truth, I had rather lose my hand, than be an encourager of such outrages as were committed last night. . . .

But, at the same time I must beg your Honor not to divulge what I now write, so that it may come to the knowledge of those enraged people, who have acted such a part; not a single person of whom, or of their Advisers, do I know. For it could do no good in the present circumstances, and the temper which they are in; and might probably bring their heavy vengeance upon myself, who am none of their friend, any farther than to wish them repentance.

But was Mayhew protesting too much? Did he worry that his sermon had gone too far?

TOMORROW: Another sermon, and another letter.

Wednesday, August 26, 2020

“Nothing Remaining but the bare walls & floors”

As evening fell on Monday, 26 Aug 1765, crowds started to gather on the streets of Boston.

It was twelve days after the town’s first big protest against the Stamp Act and the provincial stamp agent, Andrew Oliver. Back then, some men had threatened to attack Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house in the North End as well but had been dissuaded.

This time, the crowd first went to the home of Customs official Charles Paxton. His landlord convinced them not to harm that property, as I wrote back on the sestercentennial of that event. But the men did more damage at the houses of William Story, Benjamin Hallowell, and Ebenezer Richardson. Then they headed up to the Hutchinson mansion.

The lieutenant governor left several descriptions of the night which, since he was a royal official and historian, have always been included in the story of the Revolution. Here, from the Colonial Society of Massachusetts’s ongoing project to publish Hutchinson’s letters, is one of his most detailed descriptions of the event, in a letter to Richard Jackson in London dated 30 August:

It was twelve days after the town’s first big protest against the Stamp Act and the provincial stamp agent, Andrew Oliver. Back then, some men had threatened to attack Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s house in the North End as well but had been dissuaded.

This time, the crowd first went to the home of Customs official Charles Paxton. His landlord convinced them not to harm that property, as I wrote back on the sestercentennial of that event. But the men did more damage at the houses of William Story, Benjamin Hallowell, and Ebenezer Richardson. Then they headed up to the Hutchinson mansion.

The lieutenant governor left several descriptions of the night which, since he was a royal official and historian, have always been included in the story of the Revolution. Here, from the Colonial Society of Massachusetts’s ongoing project to publish Hutchinson’s letters, is one of his most detailed descriptions of the event, in a letter to Richard Jackson in London dated 30 August:

In the evening whilst I was at supper & my children round me somebody ran in & said the mob were coming.Hutchinson detailed his losses in a petition to the Massachusetts General Court, to be read here. That document indicates that the mansion was also home to:

I directed my children to fly to a secure place & shut up my house as I had done before intending not to quit it but my eldest daughter [Sally] repented her leaving me & hastened back & protested she would not quit the house unless I did. I could not stand against this and withdrew with her to a neighbouring house where I had been but a few minutes before the hellish crew fell upon my house with the Rage of devils & in a moment with axes split down the door & entred.

My son [which one?] being in the great entry heard them cry damn him he is upstairs we’ll have him. Some ran immediately as high as the top of the house others filled the rooms below and cellars & others Remained without the house to be employed there.

Messages soon came one after another to the house where I was to inform me the mob were coming in pursuit of me and I was obliged to retire thro yards & gardens to a house more remote where I remained until 4 o’clock by which time one of the best finished houses in the province had nothing Remaining but the bare walls & floors.

Not contented with tearing off all the wainscot & hangings & splitting the doors to pieces they beat down the partition walls & altho that alone cost them near two hours they cut down the cupola or lanthern and they began to take the slate & boards from the roof & were prevented only by the approaching day light from a total demolition of the building. The garden fence was laid flat & all my trees &c broke down to the ground. Such ruins were never seen in America.

Besides my plate & family pictures houshold furniture of every kind my own my children and servants apparel they carried off about £900— sterling in money & emptied the house of every thing whatsoever except a part of the kitchen furniture not leaving a single book or paper in it & have scattered or destroyed all the manuscripts & other papers I had been collecting for 30 years together besides a great number of publick papers in my custody.

The evening being warm I had undressed me & slipt on a thin camlet surtout over my wastcoat, the next morning the weather being changed I had not cloaths enough in my possession to defend me from the cold & was obliged to borrow from my friends.

Many articles of cloathing & good part of my plate have since been picked up in different quarters of the town but the furniture in general was cut to pieces before it was thrown out of the house & most of the beds cut open & the feathers thrown out of the windows.

The next evening I intended with my children to Milton but meeting two or three small parties of the Ruffians who I suppose had concealed themselves in the country and my coachman hearing one of them say, there he is, my daughters were terrified & said they should never be safe and I was forced to shelter them that night at the castle.

- Hutchinson’s sister-in-law, Grizzell Sanford

- sons Thomas (aged 25), Elisha (22), and William Sanford (13)

- daughters Sally (21) and Peggy (11)

- housekeeper Rebeckah Whitmore

- maid Susannah Townsend

- coachman Moses Vose

- “negro” Mark

- Mrs. Walker, “a widow woman to whom I had allowed a living in the house several years”

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

“Brethren, ye have been called unto liberty”

In 1765, 25 August was a Sunday, so the Rev. Jonathan Mayhew preached a sermon at the West Meetinghouse in Boston.

Mayhew was one of the town’s most radical ministers in two ways:

By 1765 Apthorp had left for London, never to return to his native Massachusetts. From there he kept up the debate by publishing A Review of Dr. Mayhew’s Remarks on the Answer to His Observations on the Charter and Conduct of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. “Yet, I think,” Apthorp wrote in conclusion about Mayhew, “his Zeal in this dispute has not been always conducted by Knowledge or tempered with Charity.”

In August 1765, Mayhew’s mind was on the Stamp Act. On the 8th he told his English supporter Thomas Hollis, “These Measures appear to me extremely hard and injurious. If long persisted in, they will at best greatly cramp, and retard the population of, the Colonies, to the very essential detriment of the Mother country.” (I’m taking these quotes from J. Patrick Mullins, author of the recent intellectual biography Father of Liberty: Jonathan Mayhew and the Principles of the American Revolution.)

On the 14th, the Loyall Nine organized the first out-of-doors protest against that new law. That evening, a mob attacked stamp agent Andrew Oliver’s office and home. Five days later, Mayhew wrote to Hollis: “I did not think the spirit of opposition to the Stamp-Act would break out so soon, in any open Acts of Violence, as it has done.” He warned that enforcing the law would require the Crown to use “a large army, or rather…a number of considerable ones, at least one in each Colony.” And that would be a Bad Thing.

Some people in Boston, Mayhew later said, asked him to preach about the Stamp Act. According to Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, “notice being given that he was to preach a political discourse he had a crowded audience” on the afternoon of 25 August. (That said, I haven’t found an account from anyone who was actually in the congregation that day.)

As his text Mayhew chose Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, chapter 5, verses 12-13:

Days later, the minister tried to recreate what he had said—or what he hoped he had said. That memorandum declared that it would be an abuse of liberty for people to “disregard the wholesome laws of Society, made for the preservation of the order and common good thereof”; to “causelessly & maliciously speak evil of their rulers,…or to weaken their influence, and proper authority”; or to “rebel against, or resist their lawful rulers, in the due discharge of their offices.”

But was the Stamp Act a wholesome law, made to preserve the common good? Could a North American stamp agent act with proper authority? Were officials who advised people to obey the new law duly discharging their offices? Mayhew’s memorandum ended suddenly without spelling out his argument about how the Stamp Act and rioting against it could both be Bad Things.

Friends of the royal government felt that Mayhew wasn’t clear enough, or even suggested that the Stamp Act was such a Bad Thing that violent rebellion against it was a Good Thing. Judge Peter Oliver later claimed that Mayhew “preached so seditious a Sermon, that some of his Auditors, who were of the Mob, declared, whilst the Doctor was delivering it they could scarce contain themselves from going out of the Assembly & beginning their Work.”

TOMORROW: Monday comes.

Mayhew was one of the town’s most radical ministers in two ways:

- Though a strong Congregationalist, he leaned theologically toward Arianism, or what in a couple of generations many upper-class Bostonians would adopt as Unitarianism.

- He was willing to argue in a famous 1750 sermon titled A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission that the English Revolution of the 1640s was a Good Thing.

By 1765 Apthorp had left for London, never to return to his native Massachusetts. From there he kept up the debate by publishing A Review of Dr. Mayhew’s Remarks on the Answer to His Observations on the Charter and Conduct of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. “Yet, I think,” Apthorp wrote in conclusion about Mayhew, “his Zeal in this dispute has not been always conducted by Knowledge or tempered with Charity.”

In August 1765, Mayhew’s mind was on the Stamp Act. On the 8th he told his English supporter Thomas Hollis, “These Measures appear to me extremely hard and injurious. If long persisted in, they will at best greatly cramp, and retard the population of, the Colonies, to the very essential detriment of the Mother country.” (I’m taking these quotes from J. Patrick Mullins, author of the recent intellectual biography Father of Liberty: Jonathan Mayhew and the Principles of the American Revolution.)

On the 14th, the Loyall Nine organized the first out-of-doors protest against that new law. That evening, a mob attacked stamp agent Andrew Oliver’s office and home. Five days later, Mayhew wrote to Hollis: “I did not think the spirit of opposition to the Stamp-Act would break out so soon, in any open Acts of Violence, as it has done.” He warned that enforcing the law would require the Crown to use “a large army, or rather…a number of considerable ones, at least one in each Colony.” And that would be a Bad Thing.

Some people in Boston, Mayhew later said, asked him to preach about the Stamp Act. According to Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, “notice being given that he was to preach a political discourse he had a crowded audience” on the afternoon of 25 August. (That said, I haven’t found an account from anyone who was actually in the congregation that day.)

As his text Mayhew chose Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, chapter 5, verses 12-13:

I would they were even cut off which trouble you. For, brethren, ye have been called unto liberty; only use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one another.Or did he? Hutchinson told Apthorp that Mayhew had left off the words after the first liberty, “the remainder of the sentence not being to his purpose.” We can’t be sure since Mayhew didn’t write out this sermon but extemporized from notes.

Days later, the minister tried to recreate what he had said—or what he hoped he had said. That memorandum declared that it would be an abuse of liberty for people to “disregard the wholesome laws of Society, made for the preservation of the order and common good thereof”; to “causelessly & maliciously speak evil of their rulers,…or to weaken their influence, and proper authority”; or to “rebel against, or resist their lawful rulers, in the due discharge of their offices.”

But was the Stamp Act a wholesome law, made to preserve the common good? Could a North American stamp agent act with proper authority? Were officials who advised people to obey the new law duly discharging their offices? Mayhew’s memorandum ended suddenly without spelling out his argument about how the Stamp Act and rioting against it could both be Bad Things.

Friends of the royal government felt that Mayhew wasn’t clear enough, or even suggested that the Stamp Act was such a Bad Thing that violent rebellion against it was a Good Thing. Judge Peter Oliver later claimed that Mayhew “preached so seditious a Sermon, that some of his Auditors, who were of the Mob, declared, whilst the Doctor was delivering it they could scarce contain themselves from going out of the Assembly & beginning their Work.”

TOMORROW: Monday comes.

Monday, August 24, 2020

“Material Culture of Sugar” Webinar from Historic Deerfield, 26 Sept.

Way back in April, Historic Deerfield was going to host a one-day forum on sugar in early New England culture. But then people recognized the Covid-19 virus had started to spread in this country, and institutions postponed their public events for a few months.

The virus is still spreading, the national government hasn’t committed to an effective strategy to stop it, and even in parts of the country where the pandemic seems more under control we have to be careful. Responsible institutions have therefore reconciled themselves to smaller gatherings and online events.

Historic Deerfield has now announced that “The Bitter and the Sweet: The Material Culture of Sugar in Early New England” will be a digital event on Saturday, 26 September. Here’s the event announcement:

See the event announcement for more details, including the exact schedule, biographies of the speakers, and how to register.

The virus is still spreading, the national government hasn’t committed to an effective strategy to stop it, and even in parts of the country where the pandemic seems more under control we have to be careful. Responsible institutions have therefore reconciled themselves to smaller gatherings and online events.

Historic Deerfield has now announced that “The Bitter and the Sweet: The Material Culture of Sugar in Early New England” will be a digital event on Saturday, 26 September. Here’s the event announcement:

The speakers will include:I own I am shocked at the purchase of slaves…Sugar is a sweet part of our everyday lives, but one with a bitter history. The insatiable demand for sugar transformed the global economy, generated new sources of commercial wealth, and fueled an unprecedented human diaspora. Domesticated in New Guinea more than 10,000 years ago and first processed in India and the Middle East, sugar emerged as a New World commodity in the 15th century. At first a rare and expensive luxury restricted to the elite, demand for sugar as an indispensable product increased exponentially during the 17th and 18th centuries in tandem with the rising popularity of the tea, coffee, chocolate, and punch it sweetened.

I pity them greatly, but I must be mum,

For how could we do without sugar and rum?

—William Cowper, Bristol Gazette, June 12, 1788

Grown and processed by enslaved Africans in the Caribbean, sugar formed one of the three legs of the trans-Atlantic triangular trade that flourished from the 16th through the 19th centuries. New England merchants sent barrel staves, building materials, provisions, and livestock to the West Indies enabling plantation owners to convert every available acre to sugar cultivation. Ships carried sugar and molasses from the plantation colonies of the Caribbean to New England rum distilleries. Merchants then shipped rum to Africa in exchange for ever-larger numbers of enslaved people carried back to the Caribbean to produce more and more sugar.

This one-day forum brings together a diverse group of historians, curators, and archaeologists to focus on the material culture and history of sugar in New England, including issues of wealth, power, refinement, status, social justice, and politics.

- Mark Peterson on how the rise of large-scale sugar production in Barbados rescued the New England colonies from economic collapse and provided dynamic growth through the colonial period.

- Brandy S. Culp on the material world fueled and shaped by sugar, encompassing the history of the trade and its human impact to the goods generated around its use.

- Justin DiVirgilio on the social and political context in which rum distilleries operated, using archeological evidence about a distillery in mid-18th-century Albany.

- Amanda Lange on the varieties of cane sugar used in 18th- and 19th-century New England households and the objects associated with tea, coffee, chocolate, and punch.

- Dan Sousa on the museum’s newly acquired group of anti-slavery ceramics, reflecting how sugar production was intimately bound up with slavery.

- Barbara Mathews on maps and artifacts demonstrating the relationships between Brazil, the Sugar Islands, New England, and the leading European powers.

See the event announcement for more details, including the exact schedule, biographies of the speakers, and how to register.

Sunday, August 23, 2020

The Point of a John Adams Presidential Library

As I noted yesterday, earlier this year Mayor Thomas Koch of Quincy raised the idea of moving John Adams’s books from the Boston Public Library, where they’ve been for a century and a quarter, to his city.

That was part of an ambitious speech as Koch began his sixth term. At the time, of course, there was no pandemic in the U.S. of A. killing a thousand people a day, squelching tourism, slowing the economy, and taking a big bite out of municipal budgets. That situation has pushed a lot of big plans out further into the future.

Nonetheless, this month, as the Patriot-Ledger reported on 14 August, Koch took the first step in trying to claim the John Adams library:

The Adams Temple and School Fund lasted into this century with its last beneficiary being the Woodward School, founded just about the time the Adams books went to Boston. A few years ago, that school sued the city of Quincy for not exercising more fiduciary care over the fund. I don’t claim to understand the ramifications of the court’s decisions, but that case might have brought new attention to John Adams’s 1822 deeds to the city.

Mayor Koch now proposes to house the books in the Adams Academy building. That was the former President’s original vision, but the books have never actually been there. By the time that academy opened fifty years later, people appear to have thought better of housing thousands of antique books and hundreds of teen-aged boys in the same space. That building is now home to the Quincy Historical Society, so it is a center of local heritage.

Koch’s proposal makes clear that he envisions the “John Adams Presidential Library” as a historical display for the public. As another example of such city projects, Koch “pointed to the $32 million Hancock-Adams Common, the park in front of city hall, as a preservation investment that current and future residents and visitors will enjoy.” The statue of John Adams in that park appears above.

When WBUR radio covered this story, it reported: “The country’s second president granted his books and papers to the people of Quincy in a deed in the 1820s.” That’s only partly true. John Adams’s deed covered his books, not his papers. The family retained his documents, and eventually the Adams Manuscript Trust donated them to the Massachusetts Historical Society. The city of Quincy has no claim on those papers.

And that brings up a major problem with this proposal for a “John Adams Presidential Library.” Presidential libraries are usually the repositories of Presidents’ papers and are always supposed to be places to study their lives and administrations. Simply having John Adams’s books would not create a Presidential library as scholars understand the term. The mayor’s comments on the project show no sign that it would be designed for researchers, not just tourists and local students on field trips.

Indeed, the mayor’s remarks to the press suggest that the driver of this proposal is to affirm local pride, to show that Quincy can boast the same historical resources as Boston. Of course, Quincy is already home to Adams National Historical Park, with the houses of two Presidents and the book collection of one—but that’s a federal facility. A “John Adams Presidential Library” would be the city’s own shrine to one of its august citizens.

On Twitter, former Adams Editorial Project staffer Christopher F. Minty (now managing the John Dickinson Writings Project) reacted to these developments about John Adams by quoting from a letter of Thomas Boylston Adams IV in 1962 when Massachusetts was considering a monument to the former Presidents. “I think it would be a pure waste of money to put up a statue or similar memorial,” that descendant stated; “The only memorial which I consider suitable to them is their writings.”

For people studying those writings, John Adams’s papers and John Adams’s books are now housed in major research libraries about half a mile apart on Boylston Street. I think the Boston Public Library’s Rare Books and Manuscripts department could use more funding, but it offers a full scholarly infrastructure. Back in 1893, the Adams Temple and School Fund said the books should go to Boston because more scholars would visit them at a bigger library in a bigger city. I think that’s still true.

That was part of an ambitious speech as Koch began his sixth term. At the time, of course, there was no pandemic in the U.S. of A. killing a thousand people a day, squelching tourism, slowing the economy, and taking a big bite out of municipal budgets. That situation has pushed a lot of big plans out further into the future.

Nonetheless, this month, as the Patriot-Ledger reported on 14 August, Koch took the first step in trying to claim the John Adams library:

The city has formally requested that the John Adams book collection be brought back to Quincy in a letter to the Boston Public Library, which has kept and maintained the 3,000 volumes for more than 120 years. Mayor Thomas Koch says he wants the artifacts returned to Quincy, the president’s final resting place, and ultimately used as the focal point for a presidential library.Mayor Koch’s request is based on the idea that that the Adams books were merely loaned to the Boston Public Library in the 1890s. I don’t see such language in the publications of the time. Indeed, as I wrote on Friday, while the Adams Temple and School Fund still referred to the books as the property of Quincy, the press of the time referred to the transfer of those books to the Boston Public Library as a “gift.”

“My objective is to return this treasure of our local and our national history to the citizens of Quincy and dedicate a presidential library of sorts to John Adams and feature his collection as its centerpiece, among other important displays of our history,” the mayor’s letter, addressed to BPL President David Leonard, said. “I fully recognize the importance of this undertaking and am willing to commit the necessary resources to see the proper care of the collection as well as prepare a suitable home for it.”

The Adams Temple and School Fund lasted into this century with its last beneficiary being the Woodward School, founded just about the time the Adams books went to Boston. A few years ago, that school sued the city of Quincy for not exercising more fiduciary care over the fund. I don’t claim to understand the ramifications of the court’s decisions, but that case might have brought new attention to John Adams’s 1822 deeds to the city.

Mayor Koch now proposes to house the books in the Adams Academy building. That was the former President’s original vision, but the books have never actually been there. By the time that academy opened fifty years later, people appear to have thought better of housing thousands of antique books and hundreds of teen-aged boys in the same space. That building is now home to the Quincy Historical Society, so it is a center of local heritage.

Koch’s proposal makes clear that he envisions the “John Adams Presidential Library” as a historical display for the public. As another example of such city projects, Koch “pointed to the $32 million Hancock-Adams Common, the park in front of city hall, as a preservation investment that current and future residents and visitors will enjoy.” The statue of John Adams in that park appears above.

When WBUR radio covered this story, it reported: “The country’s second president granted his books and papers to the people of Quincy in a deed in the 1820s.” That’s only partly true. John Adams’s deed covered his books, not his papers. The family retained his documents, and eventually the Adams Manuscript Trust donated them to the Massachusetts Historical Society. The city of Quincy has no claim on those papers.

And that brings up a major problem with this proposal for a “John Adams Presidential Library.” Presidential libraries are usually the repositories of Presidents’ papers and are always supposed to be places to study their lives and administrations. Simply having John Adams’s books would not create a Presidential library as scholars understand the term. The mayor’s comments on the project show no sign that it would be designed for researchers, not just tourists and local students on field trips.

Indeed, the mayor’s remarks to the press suggest that the driver of this proposal is to affirm local pride, to show that Quincy can boast the same historical resources as Boston. Of course, Quincy is already home to Adams National Historical Park, with the houses of two Presidents and the book collection of one—but that’s a federal facility. A “John Adams Presidential Library” would be the city’s own shrine to one of its august citizens.

On Twitter, former Adams Editorial Project staffer Christopher F. Minty (now managing the John Dickinson Writings Project) reacted to these developments about John Adams by quoting from a letter of Thomas Boylston Adams IV in 1962 when Massachusetts was considering a monument to the former Presidents. “I think it would be a pure waste of money to put up a statue or similar memorial,” that descendant stated; “The only memorial which I consider suitable to them is their writings.”

For people studying those writings, John Adams’s papers and John Adams’s books are now housed in major research libraries about half a mile apart on Boylston Street. I think the Boston Public Library’s Rare Books and Manuscripts department could use more funding, but it offers a full scholarly infrastructure. Back in 1893, the Adams Temple and School Fund said the books should go to Boston because more scholars would visit them at a bigger library in a bigger city. I think that’s still true.

Saturday, August 22, 2020

Looking at John Adams’s Things Today

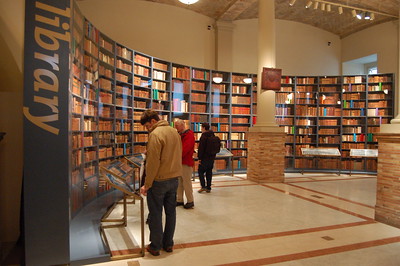

Since the Boston Public Library opened in its current location in 1895, it’s been the repository of John Adams’s book collection.

The B.P.L. had a handsome exhibit of those books in 2006-07, as shown here courtesy of Brian O’Connor. More recently it digitized the collection through the Internet Archive.

Scholars have long studied those volumes, many of which include Adams’s notes responding to what he read. Now everyone can look at images of those pages and see how, for instance, he engaged in a running debate with Mary Wollstonecraft on the French Revolution.

John Adams and his family also left a very large archive of manuscripts—letters, diaries, trial notes, drafts of essays, expense accounts, and so on. In 1956 the Adams Manuscript Trust donated all those papers to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Since then the M.H.S. has managed an extensive program to transcribe and publish the family documents, both for scholars and the public.

The text of the published papers appears online within the M.H.S. website and at Founders Online. Images of the correspondence of John and Abigail Adams, John Adams’s autobiography and diary, and John Quincy Adams’s diaries, among other documents, can also be viewed online.

The Adams family also deeded their historic houses in Quincy to the National Park Service, starting in 1946. The Adams National Historic Park complex now includes a stone building erected in 1870 for John Quincy Adams’s library, significantly larger than his father’s (though he inherited about 10% of those books).

In 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt forged a new path for handling his Presidential and other papers. He established a library on his estate at Hyde Park, New York; raised money to fund it; and turned it over to the U.S. government through the National Archives. That became a model for a new institution: the Presidential library. Soon Harry S Truman and Herbert Hoover followed that example. After the Watergate crimes, the U.S. Congress mandated that Presidents’ official papers remained part of the National Archives, no longer their personal property.

Presidential libraries have become so popular that private and public institutions have been establishing libraries for earlier Presidents. Some of those places are the repositories of the President’s papers, but others aren’t.

For instance, the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon doesn’t own Washington’s papers; those are, for the most part, at the Library of Congress and the Library of Virginia. It doesn’t own Washington’s own books; the bulk of that collection is at the Boston Athenaeum. But the library at Mount Vernon has quickly established itself as a study center with a large collection of published studies, fellowships, and public programs.

The Presidential libraries also often function as shrines to their subjects, on par with their birthplaces and mansions. Those libraries are tourist sites as much or more than anything else. There’s ongoing tension between showing each President at his best and promoting objective, scholarly assessments of his actions and legacy.

All that brings me to this year’s twist in the story of the John Adams Library. In January Thomas Koch began his sixth term as the mayor of Quincy. In his inaugural address he outlined several ambitious plans for city institutions. Among them, according to the Quincy Patriot-Ledger:

TOMORROW: How would this proposal for a John Adams Presidential Library work?

The B.P.L. had a handsome exhibit of those books in 2006-07, as shown here courtesy of Brian O’Connor. More recently it digitized the collection through the Internet Archive.

Scholars have long studied those volumes, many of which include Adams’s notes responding to what he read. Now everyone can look at images of those pages and see how, for instance, he engaged in a running debate with Mary Wollstonecraft on the French Revolution.

John Adams and his family also left a very large archive of manuscripts—letters, diaries, trial notes, drafts of essays, expense accounts, and so on. In 1956 the Adams Manuscript Trust donated all those papers to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Since then the M.H.S. has managed an extensive program to transcribe and publish the family documents, both for scholars and the public.

The text of the published papers appears online within the M.H.S. website and at Founders Online. Images of the correspondence of John and Abigail Adams, John Adams’s autobiography and diary, and John Quincy Adams’s diaries, among other documents, can also be viewed online.

The Adams family also deeded their historic houses in Quincy to the National Park Service, starting in 1946. The Adams National Historic Park complex now includes a stone building erected in 1870 for John Quincy Adams’s library, significantly larger than his father’s (though he inherited about 10% of those books).

In 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt forged a new path for handling his Presidential and other papers. He established a library on his estate at Hyde Park, New York; raised money to fund it; and turned it over to the U.S. government through the National Archives. That became a model for a new institution: the Presidential library. Soon Harry S Truman and Herbert Hoover followed that example. After the Watergate crimes, the U.S. Congress mandated that Presidents’ official papers remained part of the National Archives, no longer their personal property.

Presidential libraries have become so popular that private and public institutions have been establishing libraries for earlier Presidents. Some of those places are the repositories of the President’s papers, but others aren’t.

For instance, the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon doesn’t own Washington’s papers; those are, for the most part, at the Library of Congress and the Library of Virginia. It doesn’t own Washington’s own books; the bulk of that collection is at the Boston Athenaeum. But the library at Mount Vernon has quickly established itself as a study center with a large collection of published studies, fellowships, and public programs.

The Presidential libraries also often function as shrines to their subjects, on par with their birthplaces and mansions. Those libraries are tourist sites as much or more than anything else. There’s ongoing tension between showing each President at his best and promoting objective, scholarly assessments of his actions and legacy.

All that brings me to this year’s twist in the story of the John Adams Library. In January Thomas Koch began his sixth term as the mayor of Quincy. In his inaugural address he outlined several ambitious plans for city institutions. Among them, according to the Quincy Patriot-Ledger:

Koch said he will work to bring the John Adams Book Collection back to the city and create a John Adams Presidential Library in the Adams Academy Building. The book collection was loaned to the Boston Public Library decades ago, Koch said, because the city didn’t have the facilities to care for or display them.Now that’s not what Adams Temple and School Fund said in 1893 when it decided to move the Adams collection to the Boston Public Library. The books were then in Quincy’s recently built Thomas Crane Public Library, and there doesn’t seem to have been any suggestion they weren’t safe. Rather, the alleged problem was that nobody was coming to Quincy to study them.

“I am proud to say that thanks to the passion and hard work of a lot of people, those reasons no longer apply. That’s why I plan to petition the Boston Public Library and the City of Boston to return the books to their rightful home in Quincy,” he said.

TOMORROW: How would this proposal for a John Adams Presidential Library work?

Friday, August 21, 2020

“The most appropriate and useful place for the collection”

Yesterday I quoted John Adams’s deed donating his library to the town of Quincy.

The former President also granted the town some of the land he owned to build an academy, where the library was supposed to go, and a new Congregational church.

In February 1827 the Massachusetts General Court approved the incorporation of the Adams Temple and School Fund to oversee the property and investments, collect more money, and bring Adams’s vision to reality.

Adams was clear in his final deed about what his priorities were:

Instead, the new church was built from local granite and opened in 1828, two years after Adams died. It is now known as the “Church of the Presidents” since both he and his son John Quincy Adams attended services and were buried there.

The Adams Academy took a lot longer to raise money for. John Adams’s grandson Charles Francis Adams finally saw it become reality in 1872. Four years later, there were 140 boys studying there.

But that school ran into competition from both older academies and newer public and parochial high schools. The Adams Academy closed in 1908. The stone building then hosted other civic and charitable organizations. Since the 1970s it’s been the headquarters of the Quincy Historical Society.

In the mid-nineteenth century, John Adams’s books were housed at various places around Quincy, including the town hall. During this time, a rare copy of Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan disappeared from the collection while autograph hunters cut Adams’s signature out of others. In 1882 the fund’s trustees chose to locate the library not at the academy but in the town’s new Thomas Crane Public Library.

But that arrangement didn’t last, either. In 1893 the Boston Public Library was designing a grand new building in the Back Bay. The president of its trustees wrote to the supervisors of the Adams Temple and School Fund about their thoughts on the John Adams Library:

In November 1893, the Adams Temple and School Fund supervisors decided that “the intent of President Adams would be better carried out by placing the Library where it would be more accessible to students and investigators,” in the words of Charles Francis Adams, Jr. They approved the transfer of the volumes into the new Boston building.

Reports on this transfer, such as in the 17 Dec 1893 Boston Herald, referred to it as a “gift” from the fund to Boston’s future library. At the same time, the fund’s official resolution still referred to those books of John Adams as “the Library belonging to the city of Quincy.” So what institution had legal claim to the old President’s books?

TOMORROW: A call from Quincy in 2020.

The former President also granted the town some of the land he owned to build an academy, where the library was supposed to go, and a new Congregational church.

In February 1827 the Massachusetts General Court approved the incorporation of the Adams Temple and School Fund to oversee the property and investments, collect more money, and bring Adams’s vision to reality.

Adams was clear in his final deed about what his priorities were:

Though I presume not to dictate to the town, yet it is my wish, that the building of the Academy and the establishment of a classical master should be provided for before the Temple, of which I see no present necessity…For Adams, the resources ideally were to go toward the school, presumably the library inside it, and finally the church. There was already, after all, a serviceable meetinghouse.

Instead, the new church was built from local granite and opened in 1828, two years after Adams died. It is now known as the “Church of the Presidents” since both he and his son John Quincy Adams attended services and were buried there.

The Adams Academy took a lot longer to raise money for. John Adams’s grandson Charles Francis Adams finally saw it become reality in 1872. Four years later, there were 140 boys studying there.

But that school ran into competition from both older academies and newer public and parochial high schools. The Adams Academy closed in 1908. The stone building then hosted other civic and charitable organizations. Since the 1970s it’s been the headquarters of the Quincy Historical Society.

In the mid-nineteenth century, John Adams’s books were housed at various places around Quincy, including the town hall. During this time, a rare copy of Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan disappeared from the collection while autograph hunters cut Adams’s signature out of others. In 1882 the fund’s trustees chose to locate the library not at the academy but in the town’s new Thomas Crane Public Library.

But that arrangement didn’t last, either. In 1893 the Boston Public Library was designing a grand new building in the Back Bay. The president of its trustees wrote to the supervisors of the Adams Temple and School Fund about their thoughts on the John Adams Library:

They are so impressed with the great interest and historical value of the collection that they feel it will not be out of place to ask you if it is not possible to place it in some position where it would be more accessible to the students to whom it would be useful. . . .According to Lindsay Swift of the B.P.L., in Quincy the Adams collection “was practically unused for it was of a character little calculated to interest readers in a small community.” What’s more, the larger library’s trustees offered “a separate alcove with a suitable inscription over it” if the books came to Boston.

As the new Public Library building in Boston is nearing completion, it has occurred to the Trustees that the most appropriate and useful place for the collection would be in that building, where it would be of great use to a great number of students who resort to the Boston Public Library from all parts of the country, and where its value would be increased by the convenience of using it in connection with the large collection on kindred subjects already collected, and where it might also serve as a nucleus for one of the most important constitutional libraries in the United States.

In November 1893, the Adams Temple and School Fund supervisors decided that “the intent of President Adams would be better carried out by placing the Library where it would be more accessible to students and investigators,” in the words of Charles Francis Adams, Jr. They approved the transfer of the volumes into the new Boston building.

Reports on this transfer, such as in the 17 Dec 1893 Boston Herald, referred to it as a “gift” from the fund to Boston’s future library. At the same time, the fund’s official resolution still referred to those books of John Adams as “the Library belonging to the city of Quincy.” So what institution had legal claim to the old President’s books?

TOMORROW: A call from Quincy in 2020.

Thursday, August 20, 2020

When John Adams Gave Away His Library

In the summer of 1822, John Adams was feeling generous toward his home town and considering his legacy. The ex-President was then eighty-six years old.

On 25 June, Adams deeded to the town of Quincy two tracts of land to fund a stone “Temple” for the town’s Congregational Society, under certain conditions. On 8 July, a town meeting accepted that gift.

On 25 July, President Adams deeded more land to build a stone schoolhouse for an academy. He noted that his long-gone colleagues John Hancock and Josiah Quincy, Jr., had grown up in part on that land. On 6 August, the town accepted that gift and its conditions.

Finally, on 10 August the former President made a third gift:

The Quincy town meeting had already voted to authorize a committee to express thanks for “the gift of his very valuable library” on top of everything else.

A catalogue of Adams’s books was published in 1823 along the transcriptions of the deeds, town meeting resolutions, and other legal documents connected with his gift. That slim book listed 2,756 volumes in all. There were twenty-three pages of English books, nineteen pages of French books, five pages of Latin books, two of Greek, and two of Italian and Spanish. They were still in the former President’s possession as the committee worked on funding the academy and church.

TOMORROW: What happened to that library?

On 25 June, Adams deeded to the town of Quincy two tracts of land to fund a stone “Temple” for the town’s Congregational Society, under certain conditions. On 8 July, a town meeting accepted that gift.

On 25 July, President Adams deeded more land to build a stone schoolhouse for an academy. He noted that his long-gone colleagues John Hancock and Josiah Quincy, Jr., had grown up in part on that land. On 6 August, the town accepted that gift and its conditions.

Finally, on 10 August the former President made a third gift:

KNOW all Men by these Presents, That I, John Adams, of Quincy, in the County of Norfolk, Esquire, in further consideration of the motives and reasons enumerated in my two former Deeds, do hereby give, grant convey and confirm to the inhabitants of the town of Quincy in their corporate capacity, and their successors, the fragments of my Library, which still remain in my possession, excepting a few that I shall reserve for my consolation in the few days that remain to me, on the following conditions, viz.Adams signed that document in the presence of his nephew William Smith Shaw and his late colleague’s son and grandson, now Josiah Quincy and Josiah Quincy, Jr.

Condition first, That a Catalogue of them be made, recorded in the town books and printed, together with the three Deeds, in sufficient numbers to perpetuate the remembrance of them.

Condition second, That those books be deposited in an apartment of the building to be hereafter erected for a Greek and Latin School or Academy.

Condition third, That these books be placed under the direction of the five gentlemen mentioned in my former deeds as supervisors of the Temple and School Fund, with the addition of the Rev. Mr. [John] Whitney and the successive settled Ministers of the Congregational Society, and also of the future settled Ministers of the Episcopal Society, while they shall remain such.

Condition fourth, That none of the books shall ever be sold, exchanged or lent, or suffered to be removed from the apartment, without a solemn vote of a majority of the superintendents.

Condition fifth, The books may be removed to any place the Committee of the town shall direct, or remain where they are, at the pleasure of the Committee of the town; locked up and the keys held by the Committee during my life, and the pleasure of my Executors afterwards.

Article sixth, I make no condition of this, but submit it to the consideration of the town whether it may be expedient to build the Temple on the Hancock Lot near the Academy? Nothing would be a higher gratification to me or more honorable to my memory; and I could wish that the triangle on which the present Temple stands should be left forever as a common Training Field, and for other accommodations of the inhabitants of the town.

Article seventh, Though I presume not to dictate to the town, yet it is my wish, that the building of the Academy and the establishment of a classical master should be provided for before the Temple, of which I see no present necessity, and I cannot think that this can ever be construed a deviation from the plan and intentions of the Donor, notwithstanding any thing in the two former deeds; and if any descendant of mine should ever presume to call it in question, I hereby pronounce him unworthy of me; and I hereby petition all future Legislators of the Commonwealth to pass a special law to defeat his impious intentions, and this I think can never be adjudged an Ex post facto law.

Article eighth, It is not my intention or desire to make any condition of what follows; but I ask leave to suggest to the town the propriety of applying the income of the Coddington School lands to the uses of this Academy, and to give authority to the superintendents of the Library to apply such parts of it, as they shall judge expedient, to the purchase of books annually to augment and increase this Library. Those books to be kept by themselves in separate alcoves to be denominated the Coddington Alcoves. That gentleman’s first residence was in this town, and he [William Coddington] was an honor to it. He was a man of large and liberal mind. He removed with the excellent Roger Williams to Rhode Island, and became the father, founder, and first Governor of that colony. This will be a proper memorial of respect and gratitude for that very ancient and noble donation.

The Quincy town meeting had already voted to authorize a committee to express thanks for “the gift of his very valuable library” on top of everything else.

A catalogue of Adams’s books was published in 1823 along the transcriptions of the deeds, town meeting resolutions, and other legal documents connected with his gift. That slim book listed 2,756 volumes in all. There were twenty-three pages of English books, nineteen pages of French books, five pages of Latin books, two of Greek, and two of Italian and Spanish. They were still in the former President’s possession as the committee worked on funding the academy and church.

TOMORROW: What happened to that library?

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

“I hereby revoke all and every Sentence”

Recently I came across this advertisement in the 13 Oct 1768 Boston News-Letter:

Evidently it could. This appeared in the News-Letter on 10 November:

Whereas the Wife of me the Subscriber has eloped from me, and I am apprehensive she will run me in Debt. I hereby forbid all Persons from trusting her on my Account, as I will not pay any Debt she may contract from the Date hereof;—and all Person are forbid harbouring, entertaining or carrying her off at the Peril of the Law.That was a standard legal formula for abjuring an estranged spouse’s obligations, usually deployed by men. Can this marriage be saved?

Thomas Baker.

Boston, October 4 1768

Evidently it could. This appeared in the News-Letter on 10 November:

WHEREAS I the Subscriber here undermentioned has through the Innovations and groundless Suspicions of ill-minded Persons, treated my Wife Elizabeth Baker in a scandalous manner, by publishing her in the public Prints, and by the Cryer of this Town; be it known to all persons whatever, that I hereby revoke all and every Sentence that has been printed or said by the Cryer of this Town in my Behalf.Alas, I haven’t found any more about this Thomas and Elizabeth Baker. In fact, as of January 1769, there was another couple in Boston with exactly the same names, which rather confuses matters.

Boston, November 3, 1768.

Witness my Hand, THOMAS BAKER.

It is further expected that no Person will attempt casting any Reflections on my Wife for any Thing that is past, as they will answer the Consequence.

Tuesday, August 18, 2020

How I Zoomed My Summer Vacation

It’s the part of August in New England when the sky is overcast, the air has a chill, and hurricanes sometimes pass by. Back when I was growing up, my family always managed to be on a New Hampshire lakeside during that week, shivering in sweaters on the little beach.

So with those reminders of summer coming to an end, even though each day can seem just like the last, I’m round up links to the videos I’ve participated in since the pandemic shutdown began.

With History Camps canceled around the country this year, organizers Lee Wright and Carrie Lund turned to producing online events highlighting historical authors and sites.

Here’s my conversation with Lee and Carrie about The Road to Concord. And here are links to all the other interviews they’ve done since. On this upcoming Thursday, the conversation will feature Jim Christ, President of the Paoli Battlefield Preservation Fund.

Lee and Carrie also organized America’s Summer Road Trip to feature over a dozen historic sites across the country. I collaborated with Ranger Jim Hollister and Lee to show off both famous and little-known parts of Minute Man National Historical Park, and here’s that video.

Ranger Jim and I also had a video conversation about the weapons collected in Concord in early 1775 and what that led to. And I got to participate in the park’s group reading of Henry W. Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride.” Look for some other friendly faces in Boston’s Revolutionary history scene. There are many more videos on Minute Man’s Facebook page.

Christian Di Spigna and Randy Flood of the new Dr. Joseph Warren Historical Society are interviewing historians about smallpox in the eighteenth century and other topics. Here’s my conversation about the ripple effects of the 1764 smallpox epidemic and other topics. And here’s the whole list of videos.

Roger Williams is convening History Author Talks featuring two authors with related books plus a third as moderator. Here’s my conversation with Nina Sankovitch, author of American Rebels, with Paul Lockhart in the chair. Again, this is an ongoing series. The next session on Tuesday, 25 August, will feature Don Hagist (Noble Volunteers), Stephen Taaffe (Washington’s Revolutionary War Generals), and Gregory J. W. Unwin.

So with those reminders of summer coming to an end, even though each day can seem just like the last, I’m round up links to the videos I’ve participated in since the pandemic shutdown began.

With History Camps canceled around the country this year, organizers Lee Wright and Carrie Lund turned to producing online events highlighting historical authors and sites.

Here’s my conversation with Lee and Carrie about The Road to Concord. And here are links to all the other interviews they’ve done since. On this upcoming Thursday, the conversation will feature Jim Christ, President of the Paoli Battlefield Preservation Fund.

Lee and Carrie also organized America’s Summer Road Trip to feature over a dozen historic sites across the country. I collaborated with Ranger Jim Hollister and Lee to show off both famous and little-known parts of Minute Man National Historical Park, and here’s that video.

Ranger Jim and I also had a video conversation about the weapons collected in Concord in early 1775 and what that led to. And I got to participate in the park’s group reading of Henry W. Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride.” Look for some other friendly faces in Boston’s Revolutionary history scene. There are many more videos on Minute Man’s Facebook page.