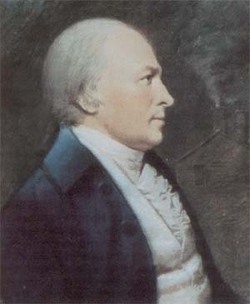

Josiah Waters (1721–1784) was a painter by training who became a respected merchant in pre-Revolutionary Boston.

Waters joined the

Old South congregation at age twenty. He was elected to several

town offices, including constable, fence viewer, clerk of the market, and finally warden, one of the most prestigious. In 1747 he joined the

Ancient & Honorable Artillery Company and filled many roles in that organization.

Also in 1747, Josiah and his wife Abigail had a son, Josiah, Jr. He grew up to work with his father in the firm of “Josiah Waters and Son” on Ann Street. In fact, it’s difficult to distinguish the two, but fortunately they seem to have acted as a unit, so that task isn’t so important. Josiah, Jr., also became a member of Old South and the Ancient & Honorables, and in 1770 he joined the St. Andrew’s Lodge of

Freemasons.

In 1768, Josiah Waters invested in land in

Maine, buying out partners to become the main proprietor of the Massabesick Plantation. That area included the modern towns of Alfred, Sanford, and what the family would modestly name Waterboro. The Maine Historical Society has digitized the

Waters account book and

map.

As of 1770, Josiah Waters, Sr., was a captain in the Boston

militia regiment. By 1772, Josiah, Jr., was his lieutenant. (I told you they came as a unit.) According to

Mills and Hicks’s British and American Register for the Year 1775, as war approached Capt. Waters’s brother-in-law

Thomas Dawes was the regiment’s major, and the adjutant, or administrative officer, was their nephew

William Dawes, Jr.

When war broke out in April 1775, it looks like the elder Waters quickly got his family out of town and followed by the 22nd. Then as a gentleman volunteer he took on the job of laying out the

fort in

Roxbury that was to keep the

British army from marching over the Neck. In his memoirs Gen.

William Heath listed Capt. Waters among the men “very serviceable in this line.” And of course Josiah, Jr., helped his father with those fortifications.

In October, Gen.

George Washington and the

Continental Congress started organizing an

army for the coming year, with revamping the

artillery regiment a big priority.

John Adams was a fan of the Waters family. On 21 October, he sent

James Warren a

letter introducing a couple of Pennsylvanians visiting Massachusetts:

I could wish them as well as other Strangers introduced to H[enry]. Knox and young Josiah Waters, if they are any where about the Camp. These young Fellows if I am not mistaken would give strangers no contemptible Idea of the military Knowledge of Massachusetts in the sublimest Chapters of the Art of War.

Earlier in the same month he wrote to Gen.

John Thomas asking about Josiah, Sr.’s work as a military engineer, among other men.

Gen. Thomas didn’t have good things to say, however. He

wrote back to Adams that Waters

I Apprehend has no great Understanding, in Either [gunnery or fortifications], any further than Executing or overseeing works, when Trased out, and by my Observations, we have Several Officers that are Equal or exceed him…

Likewise, by 2 November Gen. Washington was

writing candidly to Gov.

Jonathan Trumbull of

Connecticut:

I sincerely wish this Camp could furnish a good Engineer—The Commisary Genl [i.e., the governor’s son, Joseph Trumbull] can inform you how excedingly deficient the Army is of Gentlemen skilled in that branch of business; and that most of the works which have been thrown up for the defence of our several Encampments have been planned by a few of the principal Officers of this Army, assisted by Mr Knox a Gentleman of Worcester

Washington was impressed by Knox, whom he helped to maneuver into the artillery command, but not by Josiah Waters, father or son.

By that fall of 1775 it probably became clear to the Waterses that they hadn’t won over the commander-in-chief. They were unlikely to get appointments in the new army being organized for 1776, at least at the ranks they wanted. But they still had the respect of some New Englanders like Heath and Adams. They took on a new assignment helping to fortify New London, Connecticut. Based on how the state calculated the older man’s pay, he started that work on 25 November. Josiah, Jr., was his assistant, of course.

Before heading south, I posit, Josiah, Jr., traveled north to take stock of the family property in Maine. The Massabesick Plantation sat on the western side of that district. Just over the border in

New Hampshire was the town of Dover. And the minister of Dover was the Rev.

Jeremy Belknap.

I thus think the “Mr. Waters” who

talked to Belknap on 25 October about how the war had started was Josiah Waters, Jr. (1747-1805). We know from Belknap’s later correspondence, preserved at and published by the

Massachusetts Historical Society, that the two men were friends in the 1780s and ’90s. Waters collected orders for Belknap’s history of New Hampshire, for example. (By then everyone knew Waters as “Colonel Waters” for his highest militia rank.)

If Josiah Waters, Jr., told Belknap about how the Boston Patriots had learned of Gen.

Thomas Gage’s plans, he wasn’t speaking as just some random guy in Dover. He came from Boston, where he had close connections with the town’s militia establishment. Even beyond that, his first cousin, William Dawes, was a key figure in both smuggling artillery out of occupied Boston and

Dr. Joseph Warren’s alarm system.

The account Belknap wrote down in October 1775 is looking more reliable.

TOMORROW: More details from Mr. Waters?