This investigation started earlier this week when Dr. Melissa Johnson tweeted a question on behalf of her students: “Were any women ever tarred and feathered?”

I have Benjamin H. Irvin’s 2003

New England Quarterly article “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776” on my hard drive, so I looked at the list of incidents from 1766 to 1784 at the end. I replied: “No women tarred, but in March 1776 a crowd of Connecticut women threatened a new mother with the treatment for naming a baby after Thomas Gage. Also, women at a quilting bee in Kinderhook stuck molasses & grass on a youth in Sept 1775.”

A couple of hours later Irvin himself noted that the article noted two mid-century incidents he’d found in the secondary literature but hadn’t been able to pin down. (He added, “My suspicion is that the evidentiary record of tarring and feathering is incomplete. Maybe vastly so.”)

Irvin did his research before Google Books, Archive.org, the Hathi Trust, the Readex newspaper database, and other online databases grew so large. Was it now possible to trace back those references? I set out to try.

The first event appeared in the venerable Carl Bridenbaugh’s

Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America, 1743-1776 (1955): “Bolder prostitutes went aboard privateers, one receiving a ducking from the yardarm and a tarring and feathering from the skipper of the

Castor and Pollux.”

The second was from Alice Morse Earle’s

Curious Punishments of Bygone Days (1896): “And we read of a woman who enlisted as a seaman, and whose sex was detected, being dropped three times from the yard-arm, running the gantlope, and being tarred and feathered, and that she nearly died from the rough and cruel treatment she received.”

Earle described what’s obviously the same incident in

Colonial Days in Old New York (also 1896): “And we read of a woman who enlisted as a seaman, and whose sex was detected, being dropped three times from the yard-arm and tarred and feathered.” Note that in this passage, even though she had just discussed running the gantlope, Earle did not say this woman was forced to do that, as in her other book. So right away we can see some slippage in the details.

I found a couple of printed sources that described an event incorporating details that reappeared in both Bridenbaugh or Earle’s accounts, indicating that they were actually describing the same event. One was

Clarence Clough Buel’s article in the Century Magazine in 1894: “In one instance a woman tried to palm herself off as a male cutthroat on one of the companion privateers

Castor and

Pollux; but the ‘Gentlemen Sailors,’ on discovering her sex, ducked her three times from the yard-arm, and ‘made their negroes tarr her all over from head to foot.’”

The second was a passage from William Dunlap’s 1840

History of the New Netherlands, Province of New York, and State of New York, which

directly quoted a newspaper item dated 25 July 1743. Dunlap’s transcription deviated from the original text in small ways, most notably in turning the pair of privateers into a single vessel. Since Buel didn’t make that error, he must have seen the original article.

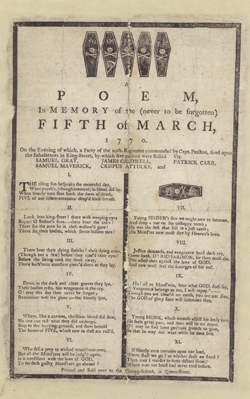

With a date and keywords, it was simple to find the actual news story at the root of all these passages. It appeared in the 25 July 1743

New York Gazette and was reprinted by newspapers in Boston and Philadelphia:

Saturday last the Men belonging to the Castor and Pollux Privateers, having found that a Person who had entered on board them two or three Days before, in order to go the Cruize, was a Woman, they seized upon the unhappy Wretch and duck’d her three Times from the Yard-Arm, and afterwards made their Negroes tarr her all over from Head to Foot, by which cruel Treatment, and the Rope that let her into the Water having been indiscreetly fastened, the poor Woman was very much hurt, and continues now ill.

That text not only pins down the date and circumstances of the incident, but it also shows how the later authors distorted it. To start with, both Earle and Bridenbaugh said this was a tarring and feathering. The original story said nothing about feathers. The feathers were a way to make a victim look more ridiculous when put on public display, but that consideration doesn’t appear to have been part of this 1743 attack. Is there a separate history of tarring as punishment, especially at sea?

Bridenbaugh stated that the “skipper of the

Castor and Pollux” attacked the woman because she was a prostitute. Earle said the punishment was because she “enlisted as a seaman.” That difference made Irvin think they were describing two separate events. The original story said the woman intended “to go the Cruize,” or enlist, so Earle’s reading was more accurate. There’s no indication this woman worked as a prostitute. Rather, she was transgressing gender lines.

Finally, both modern authors left out some notable detail. The

New York Gazette blamed “the Men” for punishing the woman, not their captains (though the captains undoubtedly held authority). It also offered the detail that the sailors “made their Negroes” put tar on the woman, presumably as a further punishment. Finally, the news story is notable in being sympathetic to the woman, despite her transgression, because of how much she suffered.