How to Save a Penny and More at Franklin’s Grave

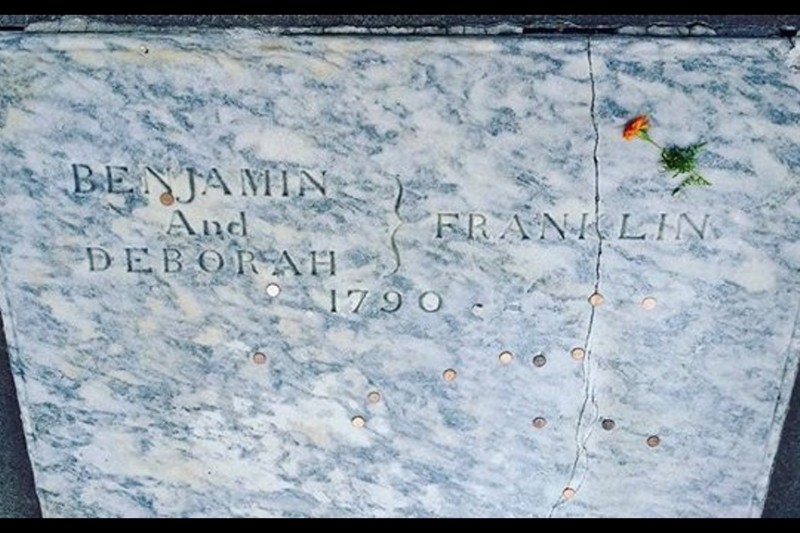

Last week the Philadelphia newspapers ran a short article about an effort to preserve the gravestone of Benjamin and Deborah Franklin.

That marble stone, in the Christ Church Burial Ground across from Independence Mall, has developed “developed a significant crack on top of the pitting caused by the tens of thousands of pennies tossed onto the marker annually in tribute to Franklin.”

The article suggested people threw those pennies on the stone “in tribute to Franklin, who coined the adage that ‘a penny saved, is a penny earned.’” But throwing pennies away is hardly saving them, is it?

No, this was just another manifestation of tourists’ wish to make their mark everywhere (while reassuring themselves they’re not actually vandalizing sites or causing damage). I recall climbing up the Bunker Hill Monument a few years back and seeing that people had shoved pennies through the wire grills on the windows, all to leave some hard sign they had passed through.

What’s more, though the “penny saved” adage sounds like something Franklin would write, he never actually did. He didn’t even quote it in Poor Richard’s Almanac, the way many other old sayings came to be attributed to him.

[CORRECTION: My source on that was wrong, as the comments below reveal. When I searched Founders Online to confirm that source, I searched for “penny saved”—but Franklin used the spelling “penny sav’d,” darn him.]

We have three examples of Franklin using variations on that adage:

But Franklin didn’t originate that saying.

According to this analysis, Thomas Fuller’s History of the Worthies of England (c. 1661) was the first book to note, “a penny saved is a penny gained.” Edward Ravenscroft’s Canterbury Guests (1695) preferred, “A penny sav’d, is a penny got.”

George Washington quoted the latter form of the adage to Anthony Whitting, an alcoholic farm manager at Mount Vernon, on 16 Dec 1792. And then again on 20 Jan 1793. And again on 5 May 1793. Whitting died later that year, or no doubt he would have read the words a lot more. Washington quoted the wisdom one last time to his last farm manager, James Anderson, on 29 Jan 1797.

At the end of 1831, the British and then American and then British political writer William Cobbett gave a lecture in Manchester in which he stated, “‘A penny saved is a penny earned,’ says the proverb.” Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register printed that version of the saying in January 1832.

But the adage wasn’t done evolving. In 1841 Gould’s Universal Index, and Every Body’s Own Book, by the American stenographer Marcus T. C. Gould, offered yet another version. A lecture in that schoolbook starts off, “Franklin has said that ‘Time is money;’ that ‘A penny saved is worth two earned.’” So American authors were starting to link versions of the adage back to Franklin.

Finally, everything came together in the form we know in the sixteenth Annual Report of the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind, published in Cambridge in 1848: “…according to Dr. Franklin, a penny saved is a penny earned.” Since then, many American sources have printed that version of the saying with that attribution. But Franklin himself said it a little differently.

Back to Philadelphia. The Christ Church Preservation Trust raised $66,000 for the gravestone restoration project before turning to GoFundMe for another $10,000. Within a day or two after local publicity hit, musician Jon Bon Jovi, his wife Dorothea, and the Philadelphia Eagles football team pledged the bulk of the money needed.

That marble stone, in the Christ Church Burial Ground across from Independence Mall, has developed “developed a significant crack on top of the pitting caused by the tens of thousands of pennies tossed onto the marker annually in tribute to Franklin.”

The article suggested people threw those pennies on the stone “in tribute to Franklin, who coined the adage that ‘a penny saved, is a penny earned.’” But throwing pennies away is hardly saving them, is it?

No, this was just another manifestation of tourists’ wish to make their mark everywhere (while reassuring themselves they’re not actually vandalizing sites or causing damage). I recall climbing up the Bunker Hill Monument a few years back and seeing that people had shoved pennies through the wire grills on the windows, all to leave some hard sign they had passed through.

[CORRECTION: My source on that was wrong, as the comments below reveal. When I searched Founders Online to confirm that source, I searched for “penny saved”—but Franklin used the spelling “penny sav’d,” darn him.]

We have three examples of Franklin using variations on that adage:

- In a 1732 Pennsylvania Gazette essay under the pseudonym Celia Single, Franklin wrote: “you know a penny sav’d is a penny got, a pin a day is a groat a year, every little makes a mickle…”

- In his 1737 almanac’s “Hints for those that would be Rich,” Franklin offered an even higher return: “A Penny sav’d is Twopence clear, A Pin a day is a Groat a Year.”

- In a 2 Oct 1779 letter on designing American coins, Franklin recommended that they display financial advice, including, “a Penny sav’d is a Penny got.”

But Franklin didn’t originate that saying.

According to this analysis, Thomas Fuller’s History of the Worthies of England (c. 1661) was the first book to note, “a penny saved is a penny gained.” Edward Ravenscroft’s Canterbury Guests (1695) preferred, “A penny sav’d, is a penny got.”

George Washington quoted the latter form of the adage to Anthony Whitting, an alcoholic farm manager at Mount Vernon, on 16 Dec 1792. And then again on 20 Jan 1793. And again on 5 May 1793. Whitting died later that year, or no doubt he would have read the words a lot more. Washington quoted the wisdom one last time to his last farm manager, James Anderson, on 29 Jan 1797.

At the end of 1831, the British and then American and then British political writer William Cobbett gave a lecture in Manchester in which he stated, “‘A penny saved is a penny earned,’ says the proverb.” Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register printed that version of the saying in January 1832.

But the adage wasn’t done evolving. In 1841 Gould’s Universal Index, and Every Body’s Own Book, by the American stenographer Marcus T. C. Gould, offered yet another version. A lecture in that schoolbook starts off, “Franklin has said that ‘Time is money;’ that ‘A penny saved is worth two earned.’” So American authors were starting to link versions of the adage back to Franklin.

Finally, everything came together in the form we know in the sixteenth Annual Report of the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind, published in Cambridge in 1848: “…according to Dr. Franklin, a penny saved is a penny earned.” Since then, many American sources have printed that version of the saying with that attribution. But Franklin himself said it a little differently.

Back to Philadelphia. The Christ Church Preservation Trust raised $66,000 for the gravestone restoration project before turning to GoFundMe for another $10,000. Within a day or two after local publicity hit, musician Jon Bon Jovi, his wife Dorothea, and the Philadelphia Eagles football team pledged the bulk of the money needed.