“More of a spectacle than a science”

Lily Ford’s Public Domain Review article “‘For the Sake of the Prospect’: Experiencing the World from Above in the Late 18th Century” drifted across my vision a while back.

She made an interesting observation about different national experiences of ballooning:

The first successful manned balloon flights were conducted in France with state support. The ascents themselves became known as “experiments”, and were concerned with an exploration of the upper air. In Britain, the Royal Society withheld support from such endeavours, so the first British ascents were underwritten, in the words of one early balloonist, by “a tax on the curiosity of the public”. This affected the cultural profile of ballooning in England: it was always more of a spectacle than a science.British balloonists, including the Boston-born Dr. John Jeffries, nonetheless tried to do science in the air. Ford’s focus was one such man, the first to try to convey the experience of human flight through graphic design:

Thomas Baldwin, an early balloonist who hired [Vincent] Lunardi’s balloon for an ascent over Chester in 1785, inscribed a long book about his one day in the air to "the principal inhabitants of Chester" who had covered his costs. Uniquely in this period, Baldwin attempted to describe his experience not only verbally, but using images: three expensively produced plates depicting the view from the balloon, the balloon in the view, and the charted passage of the balloon over the landscape.

The first image in his Airopaidia, “A Circular View from the Balloon at its greatest Elevation”, departs from established conventions of landscape representation. At a quick glance it resembles an eyeball in its spherical regularity. . . . “The Spectator is supposed to be in the Car of the Balloon, suspended above the Center of the View” (Baldwin:iv). The ground is visible in the “iris”, a central roundel which contains, upon inspection, the plan view of a town and its river. This is Chester, fondly placed at the centre of this entirely new kind of view. The town is framed by a thick “Amphitheatre, or white Floor of Clouds” (Baldwin:iv). Drawing clouds was clearly not one of Baldwin’s strengths.Baldwin even recommended laying the book on the floor or ground and looking straight down on this picture to understand it.

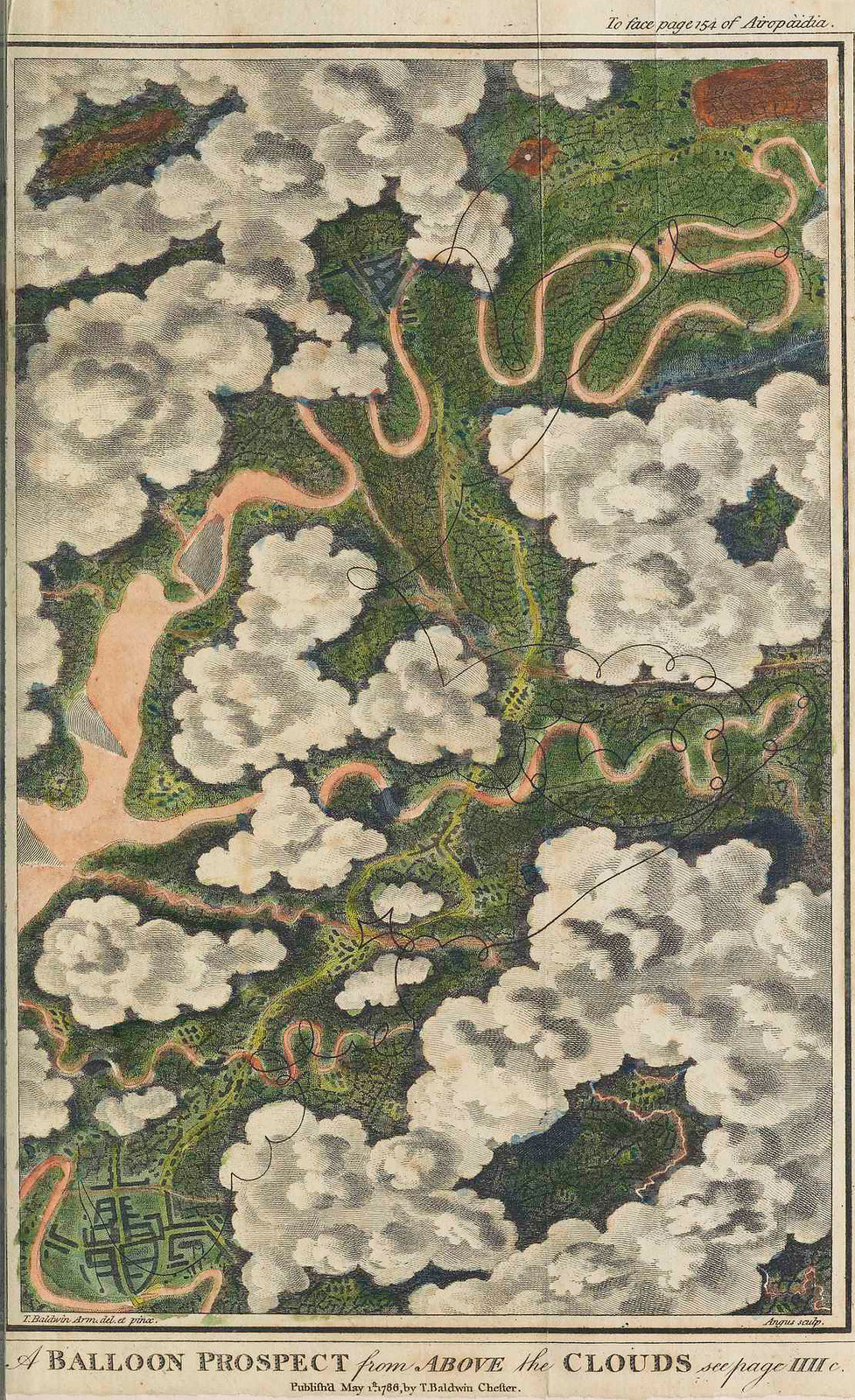

A later image is closer to the aerial views that have become entirely familiar in an age of airplanes and satellites. The main point of this picture was the path of the balloon over the landscape, as shown by the looping black thread across the landscape.

Indeed, I suspect Baldwin created this image using a map of the area around Chester rather than sketching what he actually saw from the air. Cartographers had actually produced aerial views simply through mental effort.