Finding a Franklin Bust from France

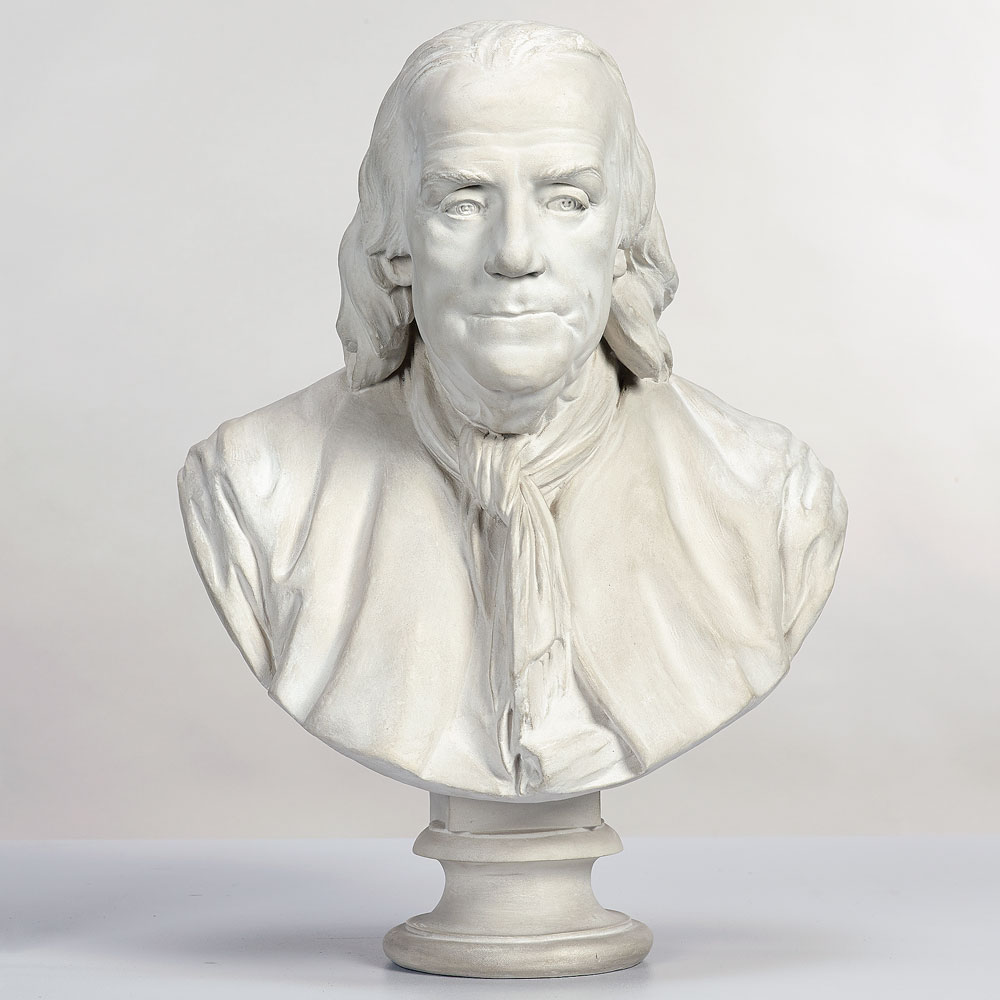

In 1949, France sent forty-nine World War I-era wooden railroad cars filled with gifts across the Atlantic to thank Americans for their aid in the aftermath of World War II. “Le Train de la Reconnaissance,” or the “Merci Train,” was a grass-roots effort to reciprocate for the “American Friendship Train”—a convoy of 700 railroad cars, packed with food and fuel sent by the American people to France and Italy in 1947.That bust of Benjamin Franklin was one of several that the artist, Jean-Jacques Caffieri, made in plaster based on his terra cotta original—a common practice. The terra cotta from 1777 remains in the Bibliotheque Mazarine in Paris, so France didn’t send over its first or only version.

Among the treasures on the Merci Train was the bust of Benjamin Franklin that Franklin had presented to France’s Royal Academy of Sciences in 1785. Upon arriving in America, it was lost and forgotten—and with it, its remarkable history.

Furthermore, Caffieri’s reputation, and even his credit for this bust, had been eclipsed by the fame of Jean-Antoine Houdon, a younger artist known in the U.S. of A. for his full-length statue of George Washington. Houdon did sculpt a bust of Franklin in 1778—just not this one.

Franklin actually preferred the Caffieri bust. “Between 1778 and 1785,” Ehrlich wrote, “Franklin ordered at least eight plaster Caffieri busts for family and friends.” Caffieri hoped that Franklin’s favor would lead to many more commissions from the new American republic, and he wrote several letters asking to be recommended.

As he left for Philadelphia in 1785, Franklin told Caffieri that each state would make its own choice of artists. He ordered one more copy of his bust for the Royal Academy of Sciences; that’s the one eventually shopped over on the Merci Train. And then he sailed off—with none other than Houdon, heading to Mount Vernon.

Ehrlich found that in 1949 the Franklin bust was presented (reportedly as a Houdon) to the Benjamin Franklin University in Washington, D.C., a business school spun off of what became Pace University. You haven’t hear of Benjamin Franklin University? It no longer exists. And thus Ehrlich was left to figure out the location of that bust today.