“A Committee exercising such extensive Powers as this”

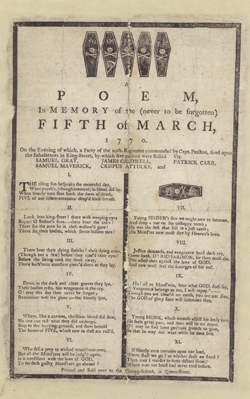

This was also dated 29 June 1774 and appeared in the same newspapers as the big one. In fact, the Boston Post-Boy printers ran it first, perhaps because it was easier to set in type.

That protest read:

WHEREAS at a Meeting of the Town of Boston, held at the Old-South Meeting-House on the 28th Instant, a Motion was made and seconded, That the Committee of Correspondence of said Town should be censured and dismissed, which being put to Vote passed in the Negative.The men who signed this protest were Edward Payne, Thomas Amory (shown above), John Amory, Samuel Elliot, Caleb Blanchard, Frederick William Geyer, John Andrews, and Samuel Bradstreet. Some were future Loyalists, others moderate Whigs. Payne was even a victim of the Boston Massacre.

We the Subscribers, being Dissentients therefrom, do now enter our Protest, grounded on the following Reasons:

First, Because that notwithstanding we think that a Committee of Correspondence, constitutionally appointed, may at any Time be useful, provided it was under proper Restrictions, and that the Letters wrote by them previous to their being sent were duly considered and approbated by the Town; yet that a Committee exercising such extensive Powers as this has done, is of dangerous Tendency.

This Committee was appointed in November 1772, to state the Rights of the Colonists and of this Province in particular, with the Infringements and Violations thereof that have been, or from Time to Time may be made; and to publish the same to the World as the Sense of the Town; and likewise to request of the other Towns a free Communication of their Sentiments on this Subject; and to make Report of the same to this Town for their Approbation; and were not authorized to publish the same until it was approved, and the Letter accompanyed by the Town; and when this Business was done we apprehend the Committee was dissolved, or at furthest at the End of the Year; and as they have not been re-chosen, we are of Opinion they do not properly now subsist as a Committee.

Because the said Committee have lately, not only without the Knowledge and Approbation of the Town, but in a secret Manner, issued out to many Towns in the Province a Covenant for Non-Consumption of British Goods, accompanied by a Letter recommending the same, signed by their Clerk, which Covenant was of the highest Importance to the Town.

Because they have also, as a Committee of the Town, aspersed the Characters of many respectable Inhabitants of this Town, in Letters written by them to the Cities of New-York and Philadelphia.

Nothing less than a Sense of its being our Indispensable Duty, to defend the Characters of our Neighbours, when we think them injured, could have induced us to give this last Reason.——

We declare we have no private Pique against any one Gentleman of the Committee, but have an Esteem for some of them, and can readily do them Justice to say, that this Conduct is so far from being consonant to the Tenor of their Actions (as far as we have known them) in the common Occurrences of Life, that we were struck with the greatest Surprize at the Discovery.

This document notably didn’t criticize the Solemn League and Covenant itself, only how the committee had promulgated it without running it by a town meeting first.

In fact, on 30 May the town had instructed the committee to write a non-consumption agreement and communicate it to other Massachusetts towns. The committee members evidently felt they didn’t have to go back to another meeting for approval of the final text.

TOMORROW: Behind the protests.