The Fighting Ground “between the Enemy & the American force”

Asa Lord was born on 29 June 1760 in Saybrook, Connecticut. Around the time he turned sixteen, he signed up for a few months of military service, and he continued to do short-term stints as the war continued.

Lord was eighteen years old in April 1779 when he enlisted in a Connecticut regiment for nine months. He was sent to Horseneck or Greenwich, on Long Island Sound, “employed in guarding the lines between the Enemy & the American force & in preparing materials for entrenchments.”

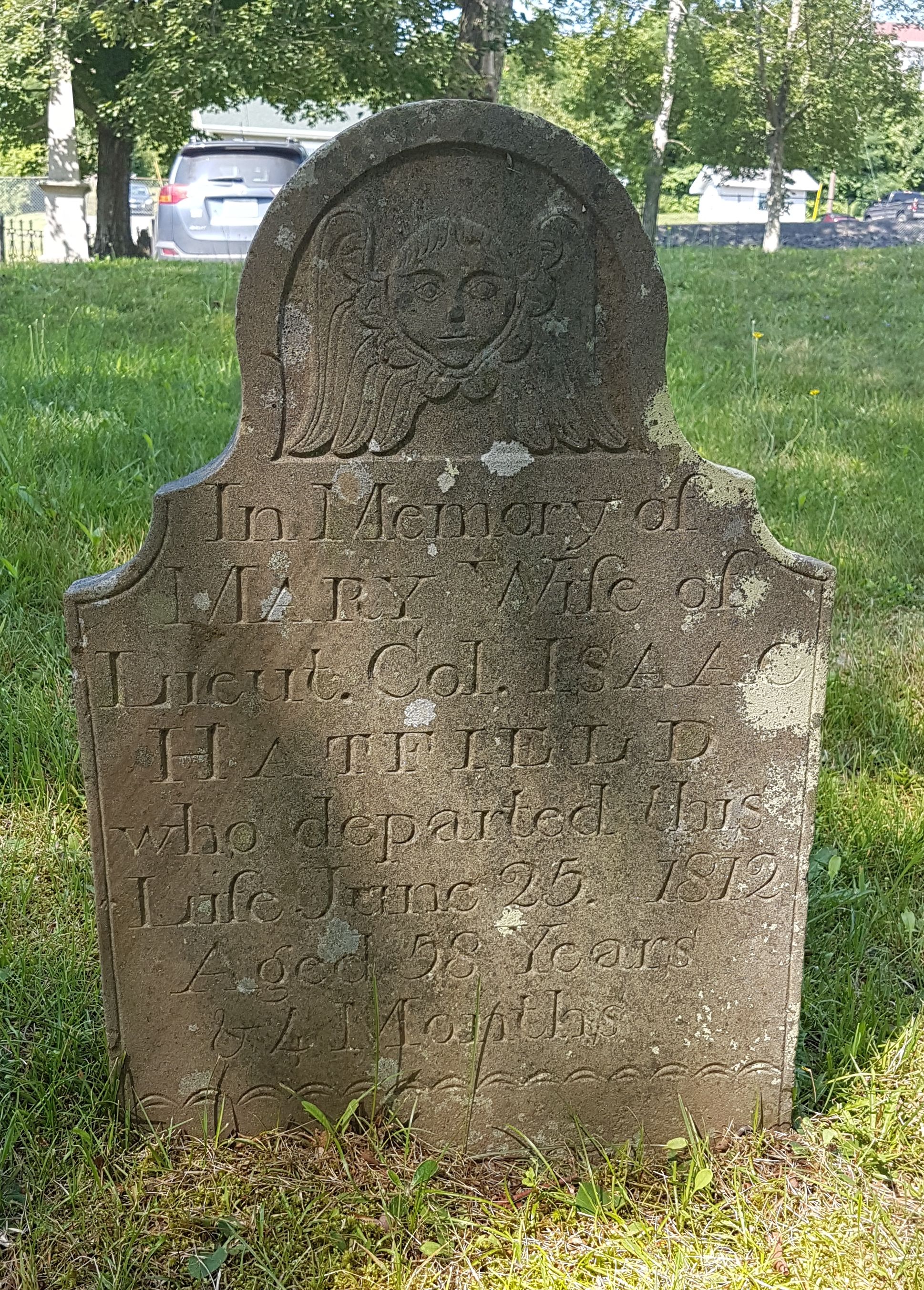

In January 1780 Lord was one of the Connecticut militiamen who raided the Morrisania, New York, house of Isaac Hatfield, Jr., a lieutenant colonel in the Loyalist militia, as I’ve been describing. Decades later Lord’s pension application stated:

The story continues in James Rivington’s Royal Gazette:

Despite that strong motivation to rescue their friends and relatives, the pursuers were too late to free the men whom the Americans had taken captive. Isaac Hatfield stated that he was “carried to New England; [and] remained Prisoner about 3 months.”

But others in the raiding party moved more slowly, as Gen. William Heath wrote:

The Coldstream Guards were sent to New York in 1779. Since Eld was born in America, that was some sort of homecoming, but unfortunately we don’t seem to have any information about exactly where or when he was born.

Ens. Eld was stationed on the British lines outside New York City, and at the start of 1780 he was put in command of a light infantry company. In his diary he wrote:

TOMORROW: Ens. Eld in the city.

Lord was eighteen years old in April 1779 when he enlisted in a Connecticut regiment for nine months. He was sent to Horseneck or Greenwich, on Long Island Sound, “employed in guarding the lines between the Enemy & the American force & in preparing materials for entrenchments.”

In January 1780 Lord was one of the Connecticut militiamen who raided the Morrisania, New York, house of Isaac Hatfield, Jr., a lieutenant colonel in the Loyalist militia, as I’ve been describing. Decades later Lord’s pension application stated:

On the 17th day of January, About one hundred & ten of their Soldiers, volunteered to go down to Morisena & Attack a British Guard Stationed there. They put themselves under Capt. Samuel Lockwood. They started about noon of the 17th—And about one oclock the next morning, attacked the Said Guard in front of their quarters. A hot engagement ensued & they finale killed most of the British guard, took nine or ten prisoners & Started on their retreatHowever, one of the Loyalist officers who had been staying with Hatfield, Maj. Thomas Huggeford (also spelled Huggerford and Hungerford), slipped away from the Connecticut men. Someone who knew him after the war described Huggeford as “a large, fleshy, middle-aged man, active and humane,” but evidently he could move with stealth and speed.

The story continues in James Rivington’s Royal Gazette:

Major Huggerford soon after effected his escape, and returning, formed a small body of Refugees, consisting of thirty-five Dragoons, and twenty-eight Infantry, under the command of Capt. [Henry] Purdy, instantly pursuing the rebels with this detachment.Because the Loyalists in that militia all came from the same communities, they had many ties. For example, captured with Isaac Hatfield was his sister Mary’s husband, Moses Knapp. The lieutenant who led the pursuing light horsemen, Samuel Kipp, was a brother-in-law of another of Isaac Hatfield’s sisters, Abigail. And eventually Samuel Kipp married Mary Knapp, daughter of Moses and Mary—i.e., his brother’s sister-in-law’s daughter.

The Infantry took post upon the heights, beyond East Chester, and the mounted, consisting of Cornet Hilat, Adjutant [John] Pugsley, two Serjeants, and twenty-nine privates, under the command of Lieut. [Samuel] Kipp, continued the pursuit, and came up with their rear between New-Rochelle and Mamarroneck…

Despite that strong motivation to rescue their friends and relatives, the pursuers were too late to free the men whom the Americans had taken captive. Isaac Hatfield stated that he was “carried to New England; [and] remained Prisoner about 3 months.”

But others in the raiding party moved more slowly, as Gen. William Heath wrote:

The militia after conducting this enterprize with much address and gallantry imprudently loitered in their retreat, were pursued & overtaken by a party of light Horse, a number of them shockingly cutRivington’s newspaper reported that the Loyalists had “killed 23, and took 40 prisoners, some of whom are wounded.” Furthermore:

We are assured that the only weapon used by Major Huggerford and his determined band of Refugees, in their attack and defeat of Capt. Lockwood’s party, was the Sabre,---and had not their horses been jaded to a stand-still, every one of the enemy would have fallen into their hands.Among the prisoners was Asa Lord, who recalled in his 1832 pension application:

Between nine & ten oclock in the morning of the 18th Jany. they were overtaken by a detachment of Queens Guards, many of the Americans killed & the Declarant & Eight others taken prisoners, carried to New York & confined in The Old Sugar House. The Declarant was confined there ten months & three days.—He was then exchanged.Yet another view of this clash comes from George Eld, who had joined the Coldstream Guards as an ensign—the equivalent of a second lieutenant—in March 1776. A copy of his diary is owned by the Boston Public Library.

The Coldstream Guards were sent to New York in 1779. Since Eld was born in America, that was some sort of homecoming, but unfortunately we don’t seem to have any information about exactly where or when he was born.

Ens. Eld was stationed on the British lines outside New York City, and at the start of 1780 he was put in command of a light infantry company. In his diary he wrote:

The two Light Infantry Companies of the Guards with the mounted refugees were ordered out under the Command of Colo. [Francis] Hall—after a march of 25 miles fell in with their [the enemy’s] rear guard—a trifling but general contest ensued—nine rebels were killed, sixteen taken prisoners, many wounded.—The rebels now appeared to the amount of 800, when on our taking an advantageous situation they retired—That was the end of this seesaw skirmish in the “neutral ground” of Westchester County. Because there was so much territory between the army lines, such raids meant long marches—the Connecticut lieutenant colonel Matthew Mead wrote of his men marching “30 miles out,” and Ens. Eld recorded a 25-mile march and an overnight stop on the way back. And at the end of all the fighting, both sides had seen some men killed and more taken prisoner.

we returned 12 miles & remained the night in some log houses & returned to the lines on being joined by a detachment sent out to Cover Our retreat.

TOMORROW: Ens. Eld in the city.