“How would those advantages accrue to us, if America was conquered?”

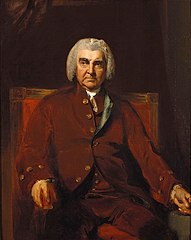

The last major speech in the House of Commons on 31 Oct 1776 about the American War came from Charles James Fox, an opposition Whig (but one who didn’t get along well with some other Whigs).

Fox spoke at length about what had brought on the war, how badly the ministry had executed it, and, at the end, how it could not win:

The Commons then voted on whether to amend the response to that speech proposed by supporters of the government. The vote was 242 in favor of Lord North’s position, 87 against. (A second vote followed, close to midnight: 232 to 83. The House of Lords had a similar debate, which the government won 82 to 26.)

In sum, for all the speeches, answered and unanswered; for all the wit and telling points; for all the Parliamentary Register reports favoring the Whigs, Lord North’s government carried the day because it had an almost 3-to-1 advantage in Parliament. The opposition’s rhetoric and logic and being ultimately right about the American War were no match for the party that had the most votes in the room.

Something to remember as we proceed through our own election season.

[ADDENDUM: It turns out the Parliamentary Register left out a speaker that Walpole recorded. I added his remarks here.]

Fox spoke at length about what had brought on the war, how badly the ministry had executed it, and, at the end, how it could not win:

What have been the advantages of America to this kingdom? Extent of trade, increase of commercial advantages, and a numerous people growing up in the same ideas and sentiments as ourselves.---Horace Walpole later wrote about this occasion:

Now, Sir, how would those advantages accrue to us, if America was conquered? Not one of them. Such a possession of America must be secured by a standing army; and that, let me observe, must be a very considerable army.

Consider, Sir, that that army must be cut off from the intercourse of social liberty here, and accustomed, in every instance, to bow down and break the spirits of men, to trample on the rights, and to live on the spoils cruelly wrung from the sweat and labour of their fellow subjects;---such an army, employed for such purposes, and paid by such means, for supporting such principles, would be a very proper instrument to effect points of a greater, or at least more favourite importance nearer home; points, perhaps, very unfavourable to the liberties of this country.

Charles Fox answered Lord George [Germain] in one of his finest and most animated orations, and with severity to the answered person. He made Lord North’s conciliatory proposition be read, which, he said, his Lordship seemed to have forgotten, and he declared he thought it better to abandon America than attempt to conquer it.That left only one member interesting in speaking, the government opponent Gen. Henry Seymour Conway. He said he respected King George III but opposed the speech he had delivered on behalf the ministry.

Mr. [Edward] Gibbon, author of the “Roman History,” a very good judge, and, being on the Court side, an impartial one, told me he never heard a more masterly speech than Fox’s in his life; and he said he observed [Edward] Thurlow and [Alexander] Wedderburne, the Attorney and Solicitor Generals, complimenting which should answer it, and, at last, both declining it.

The Commons then voted on whether to amend the response to that speech proposed by supporters of the government. The vote was 242 in favor of Lord North’s position, 87 against. (A second vote followed, close to midnight: 232 to 83. The House of Lords had a similar debate, which the government won 82 to 26.)

In sum, for all the speeches, answered and unanswered; for all the wit and telling points; for all the Parliamentary Register reports favoring the Whigs, Lord North’s government carried the day because it had an almost 3-to-1 advantage in Parliament. The opposition’s rhetoric and logic and being ultimately right about the American War were no match for the party that had the most votes in the room.

Something to remember as we proceed through our own election season.

[ADDENDUM: It turns out the Parliamentary Register left out a speaker that Walpole recorded. I added his remarks here.]