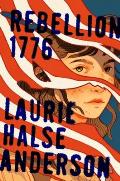

Anderson on Rebellion 1776 in Cambridge, 1 Apr.

Anderson has won awards for her Seeds of America Trilogy (Chains, Forge, and Ashes), as well as her earlier novel Fever 1793 and the picture book Independent Dames: What You Never Knew about the Woman and Girls of the American Revolution.

She’s even better known for her contemporary novel Speak, which is frequently challenged in public schools and libraries because it addresses the problem of rape. She’s one of the handful of American authors who have won the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award for children’s literature.

In an interview with Publishers Weekly, Anderson described the scope of this new book:

My book covers the traumatic effects of the Siege of Boston, the growing political divide within families and communities, and the frightening smallpox epidemic, which threatened everything. One reason I continue to write about this era is because I think we could do a better job depicting the state of the colonies at the start of the Revolution in recognizing that independence was not a done deal.As a protagonist Anderson created a thirteen-year-old girl named Elsbeth Culpepper, orphaned but taking advantage of the chaos and need for labor in Boston after the British evacuation to keep herself away from the Overseers of the Poor.

Anderson’s long conversation with Horn Book editor Roger Sutton goes deep into her research and storytelling processes:

First I had to understand what the cultural, financial, and sociological constraints were then on a thirteen-year-old kitchen maid. But then came the chaos of the siege, then the changing of the armies, and then it took a while for Boston's government to get up and running again. That chaos opened the door for me and my character to break some rules, some constraints. And then as society gets its act back together, the walls and rules come back up again.I recommend that interview for anyone writing historical fiction.

Anderson will be speaking and signing books at a ticketed event for Porter Square Books on Tuesday, 1 April. That will happen at the Marran Theater in Cambridge. Admission is $25 (which includes a signed book) or $10 (which doesn’t).