“The air is superphlogisticated”

For twenty days, a singular fog, such as the oldest man here has before not seen, has reigned in most part of Provence; the atmosphere is filled with it, and the sun, although extremely hot, for at noon the barometer rises forty five degrees, is not sufficiently so to dissipate it; it continues day and night, though not equally thick; for sometimes it clouds the neighbouring mountains.The article went on to report an unusual “storm of thunder and hail” on the solstice and the air being “greatly electrified.”

The horizon, which is usually of a beautiful azure in this country, appears of a whitish grey, the sun, which during the day is very pale, is at setting and rising quite read, and so absorbed are his rays by the fog, that one may at any time look steadily at him without being in the least incommoded.

It is an observation made by many, that the fog at some times emits a strong odour, the nature of which is not easily determined; it is so dry as not to tarnish a looking-glass, and instead of liquifying salts it drys them; the hidrometer does not ascend, and evaporation is abundant; the eyes are affected with a slight heat, and such as have weak lungs, are disagreeably affected.

However, this correspondent concluded: “The constant drought which has prevented the usual exhalations from the earth, seems to be the sole cause of this mist, the late rains having diluted the matter of which these exhalations are formed, they now ascend with their vehicle the water.”

The London printer that Thomas copied this article from then stated:

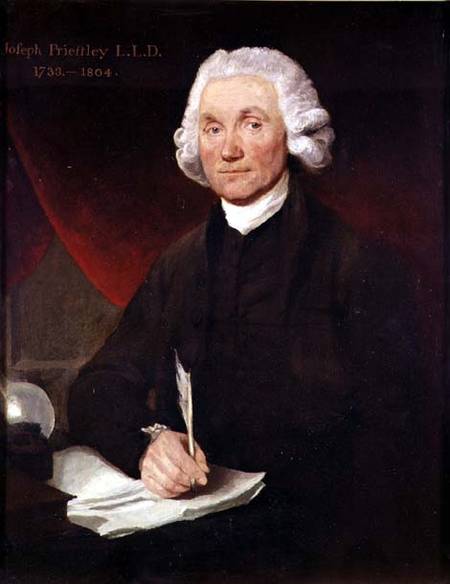

It may not be unentertaining to our readers to be informed that Dr. [Joseph] Priestly has long ago discovered that the changes in the atmosphere depend very much on the quantity of phlogiston contained in it. The excessive burning and sultry weather we have had of late shews that the air is superphlogisticated. Letters from all parts of Europe describe exactly the same season that we have had.The real reason for Europe’s strange atmospheric conditions in the summer of 1783 wouldn’t be discovered for more than another century.

TOMORROW: It wasn’t drought or phlogiston.

[The picture above shows Priestley before he took refuge in the U.S. of A.]