“So they painted the little maid”

The childhood home of Dorothy Quincy, who became Mrs. John Hancock; the second President of the Continental Congress, first signer of the Declaration of Independence and the first Governor of Massachusetts.There’s no mention of any other Dorothy Quincy.

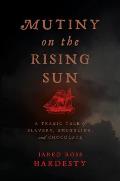

But there was (at least) one, and records are clear that that house was named after an earlier woman named Dorothy Quincy (1709–1762, shown here courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society). She was an aunt of the woman who married Hancock.

The earlier Dorothy Quincy married the merchant and mill-owner Edward Jackson. One of their children was the merchant and politician Jonathan Jackson. The other child, a daughter named Mary Jackson, married the Boston merchant and politician Oliver Wendell.

A portrait of young Dorothy (Quincy) Jackson descended in the Wendell family to Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., who became a very popular author. He wrote about the painting and its subject in “Dorothy Q.: A Family Portrait” in 1871. That poem begins:

Grandmother’s mother: her age, I guess,This was one of several poems Holmes wrote about the memory of the Revolution and its shadow on his time, such as “The Last Leaf” and “Under the Washington Elm.” He was so good at creating images and phrases that people overlook how he often simultaneously raised questions about those icons.

Thirteen summers, or something less;

Girlish bust, but womanly air;

Smooth, square forehead with uprolled hair;

Lips that lover has never kissed;

Taper fingers and slender wrist;

Hanging sleeves of stiff brocade;

So they painted the little maid.

On her hand a parrot green

Sits unmoving and broods serene.

Hold up the canvas full in view,—

Look! there's a rent the light shines through,

Dark with a century’s fringe of dust,—

That was a Red-Coat’s rapier-thrust!

Such is the tale the lady old,

Dorothy’s daughter’s daughter, told. . . .

But Holmes wasn’t correct on the painting’s subject, either. His footnote for this poem said:

Dorothy was the daughter of Judge Edmund Quincy, and the niece of Josiah Quincy, junior, the young patriot and orator who died just before the American Revolution, of which he was one of the most eloquent and effective promoters. . . . The canvas of the painting was so much decayed that it had to be replaced by a new one, in doing which the rapier thrust was of course filled up.Dorothy (Quincy) Jackson’s father was an Edmund Quincy, but a later Edmund Quincy was the father of the later Dorothy Quincy. That Dorothy Quincy did have an uncle named Josiah Quincy, but a later Josiah Quincy was the Patriot who died in 1775. So the confusion is understandable.

Nonetheless, it’s worth maintaining the knowledge of how the Dorothy Quincy Homestead got its name. It represents a confluence of the Colonial Revival and the Fireside Poets, and it stood for decades of family history. Discover Quincy’s current write-up is all about big names from the Revolutionary years only.