As I said yesterday, Katherine Glass Greene’s 1926 local history

Winchester, Virginia, and Its Beginnings, 1743-1814 contains a confused history of Gen.

Edward Braddock’s sash. Greene credited that part of her book to Mary Spottiswoode Buchanan (1840-1925). Genealogy sites reveal that Bettie Taylor Dandridge, Zachary Taylor’s daughter and owner of the sash from 1850 to 1910, had married Buchanan’s uncle.

Buchanan’s history of the sash explains for the first time fully how it traveled from Gen. Braddock to Gen.

George Washington to Gen.

Edmund Gaines to Gen. Taylor. However, it doesn’t explain how Buchanan came by that knowledge. Had she consulted

Wills De Hass’s 1851 history? Had she picked up some lore from her aunt—and if so, how had her aunt learned anything about the sash before it reached her father? Had Dandridge or Buchanan learned more about the sash through conversations with old families in Virginia? There’s no way to tell.

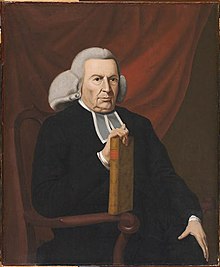

Buchanan’s narrative starts with the dying Braddock (illustrated above) giving his sash to Washington, a young volunteer aide, and saying that it had belonged to his father before him. To my knowledge, that detail hadn’t appeared in any previous printed source. And there doesn’t seem to be any evidence to confirm it.

Weaver

Carol James reports that the date “1709” is woven into the sash and suggests that Braddock’s father graduated from military school in that year. In fact, the elder Braddock was already in the Coldstream Guards as a lieutenant colonel (with the brevet rank of major general, just to confuse things). Instead, 1709 was one year before the younger Braddock joined the Coldstream Guards himself as a fifteen-year-old ensign. Thus, the sash might have been a sort of graduation gift for young Edward as he was about to embark on his own military career.

Buchanan then wrote that Washington gave the sash to his nephew

Fielding Lewis (1751-1803), whose daughter married a “Colonel Butler of Louisiana,” and Butler asked Gaines to send it out to Gen. Taylor after his early victories in the Mexican-American War. But that doesn’t match the genealogical details of Fielding Lewis’s family.

However, I found another family line that matches

some of Buchanan’s details, suggesting she received information that was garbled but originally well founded. I suspect the sash went to Washington’s step-granddaughter Eleanor Parke Custis (1779-1852), who married his nephew Lawrence Lewis (1737-1839), brother of Fielding. They had a daughter named Frances Parke Lewis (1799-1895). She married Edward G. W. Butler (1800-1888). His middle initials stood for “George Washington,” of course. After

his father’s death he had become a ward of

Andrew Jackson, just in case this story didn’t have enough generals and Presidents already.

According to the finding aid for his family’s papers (

P.D.F. file), Edward G. W. Butler served as an aide de camp to Gen. Gaines, settled in Louisiana, and retired from the U.S. Army with the rank of colonel. He thus matches all the clues to the man who sent the Braddock sash off to Gen. Zachary Taylor’s army:

- his wife was a direct descendant of Martha Washington, thus a plausible owner of a garment from Mount Vernon.

- his wife’s father was one of Gen. Washington’s Lewis nephews.

- he was “Colonel Butler of Louisiana,” as Buchanan said.

- he was “a gentleman at New Orleans,” as De Hass understood.

- he had a close connection to Gen. Gaines.

So I suspect the Butlers, pleased with the early American success against Mexico, decided to pass on a precious family relic to a new hero of the American army.

One mystery that the different sources raise is whether the Butlers wanted their relic to go to Taylor himself or to a soldier whom that general deemed particularly worthy. Some of the stories hint at the latter. But Taylor thought the gift was meant for him, and it might have been too

awwwkward to tell him otherwise.

In any event, the sash is back at

Mount Vernon now, having spent decades in the custody of Taylor’s daughter. And though some of the stories told about it seem poorly supported and others garbled, I think the evidence suggests it’s an authentic artifact owned by Edward Braddock from 1709 to 1755 and by George Washington from 1755 probably to his death.