Yesterday Ray Raphael described a challenge he set for himself: find a bunch of individuals to follow through the Revolution whose stories could also tell the story of the founding of the U.S. of A. He chose seven people. As a proud owner of a copy of the resulting book, Founders, I can’t fault those choices. But just for fun, I can second-guess them.

Yesterday Ray Raphael described a challenge he set for himself: find a bunch of individuals to follow through the Revolution whose stories could also tell the story of the founding of the U.S. of A. He chose seven people. As a proud owner of a copy of the resulting book, Founders, I can’t fault those choices. But just for fun, I can second-guess them.

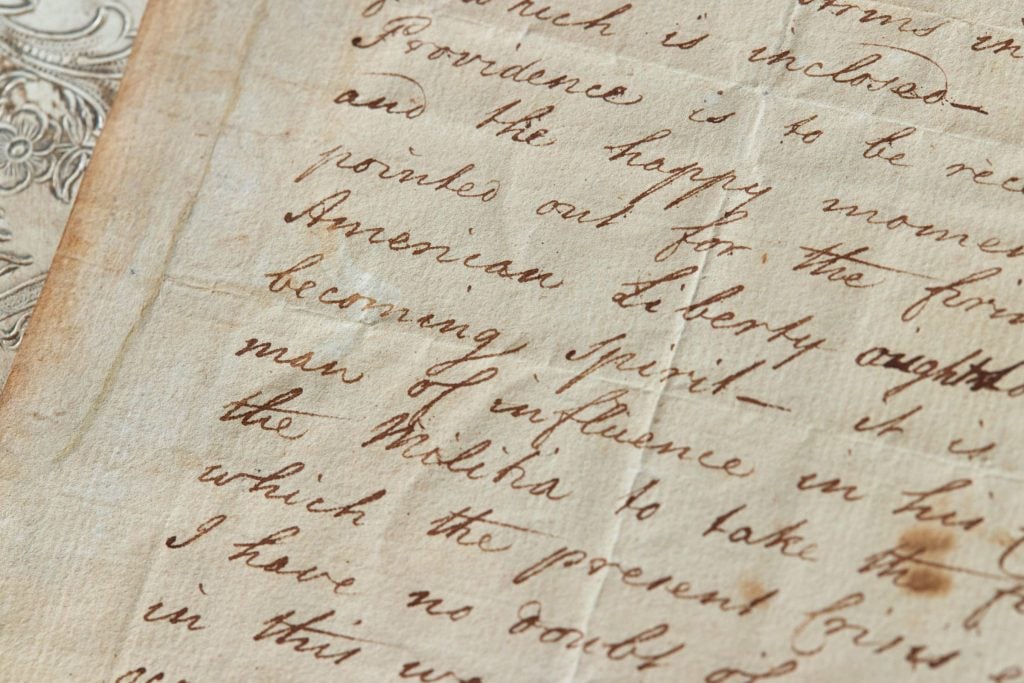

Ray wrote that George Washington is virtually a given. So naturally, to be perverse, I have to question that conclusion. Henry Knox (shown here, later in life) spent nearly the whole war at Washington’s side, so it would be possible to follow the Continental Army’s top command through his eyes rather than through the commander’s. And Knox would bring some further advantages:

- He was present at the Boston Massacre and may have been a crucial informer for Paul Revere just before the war.

- After Washington’s first farewell in 1783, Knox became Secretary of War for the Confederation while the commander went home to Mount Vernon.

- Knox’s alarmist letter to Washington about Shays’ rebellion convinced the older man to throw his prestige behind a movement for a new constitution.

- Knox served as Secretary of War again under President Washington.

- Knox’s personal story from fatherless apprentice bookseller to general, large landowner in Maine, and founder of the Society of the Cincinnati exemplifies the social mobility possible in the Revolution.

Following

Nathanael Greene offers some of the same possibilities: involvement in prewar conflicts (Greene was probably involved in the

Gaspee incident of 1772) and social mobility. In addition, his handling of the Continental forces in the southern states was crucial to the end of the war. Greene’s support for

black soldiers is interesting, as is his turn to being a southerner with his own

slave-labor plantation.

Such a book would need to follow someone deeply involved in running the American government—i.e., the

Continental Congress—during and shortly after the war. My perverse suggestion for that figure is

James Lovell. Son and assistant of the

Loyalist master of Boston’s South Latin School, he was a Whig politics newspaper essayist and orator. The British military arrested him as a

spy in 1775 after officers found his letters on

Dr. Joseph Warren’s body. He was reportedly taken to Halifax in chains.

After James Lovell was exchanged and returned to Massachusetts, the state elected him to the Congress. He supported Gen.

Horatio Gates over Washington in 1777, and wound up virtually running American

foreign policy and intelligence efforts since no one else wanted those responsibilities so badly. His father and siblings were in exile, and his illegitimate son was in the Continental Army. For added interest, in Philadelphia he reportedly roomed in a brothel while his wife and children were back home in Boston. On the down side, Lovell’s a hard man to understand—

John Adams reportedly paced the floor in Holland, trying to figure out what his official instructions meant—and to sympathize with.

Another potentially exemplary character is

Thomas Machin, a British veteran who ended up as a captain in the American engineering corps. He oversaw the effort to build a chain of obstacles across the Hudson River to prevent the

Royal Navy from sailing too far north—a major industrial undertaking in a sparsely settled area. Later Machin was one of the

artillery officers who accompanied Gen.

John Sullivan on an expedition against the Crown’s

Native American allies in upper

New York. And, as a kicker, the standard story of Machin before joining the Continental Army in 1776 is a lie; this

immigrant (or his descendants) reinvented his life in the New World.

For a southern perspective, I might consider

John Laurens: son of a bigwig in Congress, young Continental Army officer,

proponent of emancipation,

prisoner of war, diplomat, and army officer again. Regardless of what far one concludes that Laurens went with

Alexander Hamilton, the close relationship of those two young men shows how military service shaped them.

A book like this needs at least one female figure. Since most women, even those who became involved in political causes, stuck close to their homes, I’d look for candidates in the Middle and Southern states where most of the fighting was. Those women saw the most of, and suffered the most from, the war.

One possibility would be

Esther Reed of Pennsylvania: wife of a Continental Congress delegate, military officer, and governor. In 1777 she had to flee from her home. Three years later she organized an effort to support the army, struggling against both wartime shortages and Washington’s expectations for women.

Another candidate is

Annis Boudinot Stockton of New Jersey, who became a refugee in 1776. She wrote some

political poetry, and had a close-up look at developments in the government through her brother,

Elias Boudinot; son-in-law,

Dr. Benjamin Rush; and husband,

Richard Stockton. Unfortunately, little of her writing is very personal.

And of course a book like this needs to reflect the American enlisted man’s experience. One possibility would be to stitch together three or four people’s accounts of serving in the ranks, both to cover the waterfront and to emphasize how the army was composed of many men working together rather than individuals standing out on their own. (Yes, that goes against the very idea of focusing on individuals that Ray set out to try.)

Among the soldiers who left enough personal material to follow might be fifer and private

John Greenwood, privateer sailor and prisoner of war

Ebenezer Fox, and soldier’s wife and camp helper

Sarah Osborn. Adding dragoon

Boyrereau Brinch to that mix would mean bringing in the rarely documented African-American soldier’s experience.

Folks might notice that a lot of my choices lean toward people from greater Boston, simply because I know that region best. In addition, my list leaves out some really obvious candidates. I didn’t pick any of the people Ray Raphael followed in

Founders, even if they’d be my first choices as well—which is a good clue to the names he actually picked.