Continuing my exploration of the

Creating a Federal Government website, I looked up another man active among Boston Whigs before the war who I knew received a federal appointment afterward:

James Lovell.

I found him, but found that his name was amalgamated with his son’s. Poking around more, I saw a good genealogy website mixing that son up with

another son.

At the same time, the Creating a Federal Government site has filled in some information about the Lovells that I didn’t have when I

wrote about them back in 2008. So I’m going to try to sort things out.

James Lovell (1737–1814) was the respected usher, or assistant master, at Boston’s South Latin

School in the 1760s and early 1770s. He delivered the first official oration in memory of the

Boston Massacre. In the summer of 1775, the royal authorities arrested him for corresponding with

Dr. Joseph Warren and at the

end of the siege took him to

Nova Scotia as a

prisoner.

Released in an exchange, Lovell was chosen by the

Massachusetts General Court to be a delegate to the

Continental Congress. He was very active there, basically managing the

diplomatic corps for a few busy years.

When Lovell went home to Massachusetts, the national government rewarded his service with an appointment which may not have required a lot of work: naval officer for the port of Boston. He kept that post until his death, through both Federalist and Jeffersonian administrations. In January 1809, for example, he placed an advertisement in the newspapers warning that he would follow his duty in enforcing the Embargo Act, unpopular or not. (It was about to be replaced, anyway.)

Lowell signed that advertisement with his full name: “James Lovell.” However, he’s been

entered into the Creating a Federal Government website under the name of his son James S. (for Smith) Lovell (1762–1825).

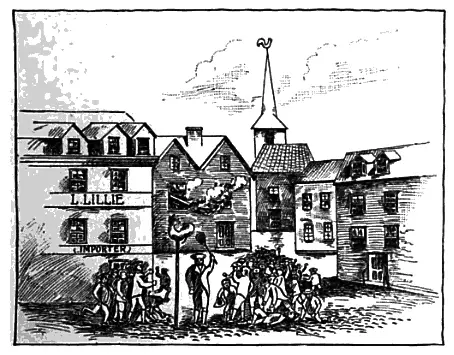

James S. Lovell was a merchant in Boston, selling

tobacco,

sugars, alcohol, and other commodities from his shop on State Street and then beside the Town Dock. By the 1790s he was investing in

ships. In February 1793 he was moderator for

Boston’s Civic Festival supporting the

French republic, and three years later on the committee of the chamber of commerce.

James S. Lovell’s most visible governmental appointment was a local one: Inspector of Police in 1798. In that capacity he made regular reports to the public about the yellow fever epidemic. The following year, the

selectmen authorized him to deal with people who wanted to buy “the Manure, to be taken from the streets of Boston.”

But then in 1801 James S. Lovell was judged bankrupt. He kept a lower profile for several years. In 1820, according to the Creating a Federal Government website,

Lovell was appointed gauger, weigher, and inspector in the Boston

Customs office. Two years later someone signing himself (or herself) “Radical” in the

Boston Courier reported the Customs department salaries, including “James S. Lovell, weigher and guager, [$]3466.99.” At that time Lovell was helping to sell a cotton factory in

Connecticut, advertising that he could meet with people “at the Custom-House, Boston, or his residence,

Newton Plain.”

James S. Lovell died in Newton in December 1825, described in Boston newspapers as “the eldest and only surviving son of the Hon. James Lovell, deceased.”

But that wasn’t true. James S. Lovell had an older half-brother still living, and to add to the confusion that man was also named James.

While he was a student at

Harvard College back in the 1750s, the future schoolteacher James Lovell had fathered a

child with the daughter of the college steward, Susanna Hastings. That boy was born in 1758 and grew up for several years in

Cambridge as James Hastings. About 1770, he came into Boston, joined his father’s household, and assumed the Lovell surname.

The younger James Lovell graduated from Harvard College himself in 1776 and then joined the

Continental Army. He served under Col.

Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, gained the rank of major, and married Ann Reid, a rich South Carolina widow.

In 2008 I wrote that this James Lovell “lit out for New Orleans” when he couldn’t get his hands on his wife’s inheritance. His years in the new Louisiana Territory, from 1806 to 1811, exactly correspond to the

tenure of a James Lovell in the Customs office at New Orleans. Newspapers confirm he was appointed Surveyor in May 1806, Inspector of the Revenue in 1807. So now we know how he supported himself.

The younger James Lovell went back to South Carolina in 1811, prompting his wife to take legal steps to preserve her property. Eventually they quarreled again, and he left. But he lived in Orangeburg until 1850, far outdistancing his younger half-brother.

Finally, in researching these men, I came across information to fill another hole in my old post. The senior James Lovell had another son named

John Middleton Lovell, born in 1763 and thought to have died around 1799 (shown above). I didn’t have much to say about him. Now I can report that he was also in business in Boston in the early 1790s, with a shop on Long Wharf; his brother James S. handled business for him while he invested in

Dedham real estate.

In March 1795, John M. Lovell joined the U.S. Army as lieutenant and adjutant of the Corps of Artillerists and Engineers. That appointment is also

noted at the Creating a Federal Government website. In that capacity he advertised for deserters in the

Columbian Centinel and other New England newspapers. He administered a

movement of troops from Pittsburgh to Fort Adams in the Mississippi Territory in 1798.

In March 1799 Lt. Lovell was still in the Mississippi Territory, negotiating an agreement with

Manuel Gayoso de Lemos,

Spanish governor of neighboring Louisiana, to discourage desertion. His commander, Gen.

James Wilkinson, wrote to

Alexander Hamilton to

boast of the results.

On 7 Jan 1800 the

Massachusetts Mercury ran this death notice:

At the Natchez, JOHN LOVELL, Esq. Aid-de-Camp to Gen. Wilkinson, and son of the hon. James Lovell, of this place.

According to a

21 Apr 1800 letter from

Caleb Swan, paymaster general of the army, “Mr Lovell died on the 24 of October 1799.”