Fort Phoenix in

Fairhaven overlooks the site of what’s often called, especially in Fairhaven, the first naval fight of the Revolutionary War. (People in Machias,

Maine, disagree.)

As Derek W. Beck described in

this article for the Journal of the American Revolution, the action started on 11 May 1775 when “a barge from Capt. Linsey’s brig”—H.M.S.

Falcon under Capt.

John Linzee—stopped a sloop in Buzzard’s Bay. (Linzee shown here courtesy of the

Linzee Family Association.)

That sloop was owned by Simeon Wing of Sandwich and commanded by his son Thomas. According to a June report from the Sandwich committee of correspondence, the Wings’ ship

hath been plying, as a wood boat, between Sandwich and Nantucket for some years, and it hath been the usual practice to settle with the custom house once a year, the officer always giving them their choice of paying twelve pence per trip, or the whole at the year’s end: and this hath been, we find, on examining, the common practise with other vessels which have followed the same business at the same place.

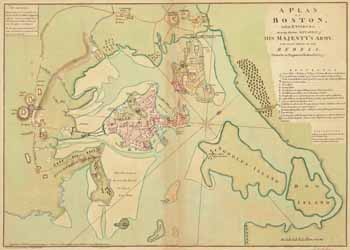

That arrangement meant, however, that the sloop had no clearance papers for that particular voyage. Linzee seized it. The historian Richard Frothingham later understood that the captain planned to use vessels he captured to “freight sheep to Boston” from

Martha’s Vineyard, feeding Gen.

Thomas Gage’s

besieged garrison.

Following normal protocol, Linzee transferred some of his crew onto the Wings’ sloop to sail it into a friendly harbor. Midshipman Richard Lucas was put in charge of “eight seamen, three

marines, a gunner, and a surgeon’s mate,” as Beck (using British naval sources) recounts.

Then the British officers learned about another vessel ripe for seizure. The Sandwich report stated: “An

Indian fellow, on board of Wing’s vessel, informed Capt. Linsey of said [Jesse] Barlow’s vessel, which had brought a cargo lately from the

West Indies, and was laden with provisions, in Buzzard’s Bay.” That Native American sailor evidently saw a better future allying with the

Royal Navy.

Linzee sent the Wings’ sloop after “Barlow’s vessel” and the provisions it carried, quite possibly intended for the provincial army. But by the time Midn. Lucas had caught up with that ship in

Dartmouth harbor, it had been unloaded. He seized it anyway. Then “both vessels, with all the crews and passengers, were taken, and proceeded to the cove to Captain Linsey.”

Barlow, a young man from Sandwich, was determined to get his sloop back. He “made application to some people at Dartmouth” for help. At the time, that town still encompassed modern New Bedford, Acushnet, and Fairhaven. Dartmouth was dominated by

Quaker merchants who were not enthusiastic about the war and how it disrupted their trade. Barlow therefore went to men in the Fairhaven village, who were reportedly having a

militia drill on the afternoon of Saturday, 13 May.

Barlow offered to put up half the money to arm the 40-ton

whaling ship

Success with two swivel guns and an extra large crew for fighting. Two militia officers—Daniel Egery and Nathaniel Pope—gathered twenty-five to thirty volunteers, including drummer Benjamin Spooner. In the shorter of two accounts later published by local historians, Pope’s son related that the bulk of the men hid below deck as the

Success sailed out of Fairhaven on Sunday morning:

Father had the deck, managing affairs there, and Captain Egery, with the drummer, was in the cabin. Captain Egery came on deck to counsel, at father’s foot-rap. There was one other man and a boy, I think, on deck.

The

Success spotted Barlow’s sloop in the waters between Buzzard’s Bay and Martha’s Vineyard. Only one sailor and one armed Marine were on deck. Pope steered his ship close before stomping for Egery. Spooner’s drum sent the militiamen charging up onto the

Success’s deck.

The Marine set down his gun and ran to cut the anchor cable of the prize sloop so it could move off, but the

Success was too close. Pope shouted for the British men to stay still or be shot. His crew grappled the two ships together and boarded the prize. Pope’s son wrote, “the thirteen

prisoners were disarmed and placed below, their position secured by the weight of cable and anchor put over the gangway.”

Egery and Pope then consulted on what to do next. Pope’s son later wrote that they sent the recaptured prize back to port, but British sources suggest that the provincial officers took the

Success and Barlow’s sloop together out to look for the other captured ship—the Wings’ firewood boat. Midn. Lucas was on board that sloop along with most of his loyal sailors and Marines.

TOMORROW: Shots fired, and the aftermath.