After the publication of “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Henry W. Longfellow in 1860, there was a lot more attention on the silversmith and his activity on 18-19 Apr 1775.

Little stories that

Paul Revere’s descendants had told within the family soon became parts of America’s national story. Some of those tales do, as W. S. Gilbert wrote, “give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative.” Maybe too much artistry.

Are all those anecdotes reliable? Were any created to entertain and instruct

children, who then grew up with them as unquestionable truth?

We can say for sure that those dramatic stories came from, or were supported by, descendants of Paul Revere. They’re not just random folktales.

One source was John Revere (1822-1886), son of Joseph Warren Revere (1777-1868), the silversmith’s eleventh child. Since Joseph Warren Revere wasn’t alive in 1775, he had only secondhand knowledge of that April through his parents or siblings. Likewise, John Revere never knew his grandparents nor most of his father’s siblings, so his knowledge was probably thirdhand.

Paul Revere’s own 1798 description of his ride said simply: “two friends rowed me across Charles River.” In a letter dated 11 Oct 1876, quoted by Elbridge H. Goss in his 1891 biography of Revere, John Revere wrote more, starting with how that boat was hidden under “a

cob-wharf at the then west part of the town, near the present Craigie Bridge,” which is now the Charles River Dam.

The two men who rowed Revere across remained publicly unnamed for a century. In November 1876 the

Old South Meeting House exhibited a “Pocket-Book of Joshua Bentley, the Ferryman who carried Paul Revere across to

Charlestown,” then owned by a descendant in

Lexington.

Joshua Bentley (1727-1819) is variously described as a boatbuilder and a ship’s carpenter. He “lived directly opposite Constitution Wharf,” according to a grandson. In the late 1880s that was on Commercial Street near Hanover Street, sticking out the top of the North End. (The current Constitution Wharf is in Charlestown.)

The Bentley family was rising in society. Joshua’s second son,

William, graduated from

Harvard College in 1777 and became a

minister in

Salem, as well as an opinionated diarist. In 1780 the

Massachusetts General Court appointed Joshua Bentley himself as clerk of the laboratory assembling

artillery shells. For that reason, Boston’s 1780 tax records identify him as “Clark to Conll [

William] Burbeck,” the comptroller of that state enterprise. Bentley’s family recalled him as a ”commissary.” So he was part of the same crowd of socially mobile, politically active mechanics as Revere. Eventually Joshua Bentley moved out to

Groton to live with a daughter, and he was buried there.

Citing John Revere’s 1876 letter, Goss identified the other rower as shipwright Thomas Richardson. This letter added that “Richardson, with two others, laid the platform for the American guns at

Bunker Hill; one of the three was killed by a cannon ball from the British.” However, Goss also quoted that letter as saying, “John Richardson, his brother, was with Paul Revere in notifying the inhabitants of Charlestown of the intention of the British to march to

Concord.” Does that suggest that John, not Thomas, was in the boat? Without the full letter, there’s some ambiguity.

The 1780 tax records show a bevy of Richardsons working as shipwrights in the North End, including John; John, Jr.; and Thomas. The elder John was presumably the one who died in 1793 at age seventy-seven; he lived near the

North Church. Another John Richardson died in 1789; that could have been John, Jr., but the name is too common to be sure.

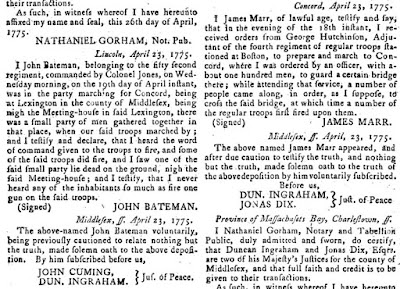

There are two delightful—perhaps too delightful—anecdotes about Revere’s departure from Boston. One was first put into print by Samuel A. Drake in his

History of Middlesex County (1879):

A tradition also exists in the Revere family, that while Paul and his two comrades were on their way to the boat it was suddenly remembered that they had nothing with which to muffle the sound of their oars. One of the two stopped before a certain house at the North End of the town, and made a peculiar signal. An upper window was softly raised, and a hurried colloquy took place in whispers, at the end of which something white fell noiselessly to the ground. It proved to be a woollen under-garment, still warm from contact with the person of the little rebel.

John Revere stated in his 1876 letter: “The story is authentic of the oars being muffled with a petticoat, the fair owner of which was an ancestor of the late John R. Adan, of Boston; Mr. Adan having repeated the account to my father within a few years of his decease.”

City councilor John Richardson Adan (1794?-1849) lived in a house originally built in the seventeenth century and standing on North Street as late as 1893, as shown above. Adan also stated that his grandfather was the last person

Dr. Joseph Warren spoke to before leaving town on the Charlestown ferry early on 19 April. So he definitely wanted people to know about his ancestor’s connections with famous Revolutionaries.

What else can we find out about that anecdote?

John R. Adan’s parents were Thomas Adan (also spelled Eden) and Mary Swift, who married in 1791. Mary’s father was a shipwright named

Henry Swift (1746-1789?), captain of the North End gang during the 1765

Stamp Act demonstrations. In 1768 Henry Swift married Mary Richardson—a daughter of shipwright John Richardson, Sr.? In 1798 Mary Swift was taxed for what appears to be the house shown above, then said to be at the corner of Ann Street and North Street. (The name of Ann Street was later changed to North Street, and North Street to North Centre Street.)

So here’s a scenario to test: Thomas or John Richardson realized he and Joshua Bentley needed cloth to muffle their oars while they rowed Paul Revere to Charlestown. Richardson went to the house of his sister, now Mary Swift. She supplied a petticoat. The story and the house descended in her daughter’s family to her grandson, John R. Adan.

(Another measure of how small Boston society was: In the 1820s John R. Adan served on the city council with John Dumaresque Dyer,

mentioned yesterday.)

Yet another family tradition came from a different branch of the Revere family. The silversmith’s daughter Mary (1768-1853) married Jedediah Lincoln of

Hingham. Their grandson William Otis Lincoln (1838-1907) told Goss that he had “often heard his grandmother tell this” story:

When Revere and his two friends got to the boat, he found he had forgotten to take his spurs. Writing a note to that effect, he tied it to his dog’s collar and sent him to his home in North Square. In due time the dog returned bringing the spurs.

Mary Lincoln witnessed the events of April 1775 as a child, so she could indeed have seen this happen or heard about it immediately afterward. However, this is also literally a grandmother’s tale, and it would definitely have entertained the grandchildren. So it seems the least likely of these legends.