“What Stock you had upon the Island”

Cattle and sheep could graze on the natural grasses, taking in adequate water and salt, and they couldn’t run away.

That meant that as the Revolutionary War began, several islands had a lot of animals on them, as well as pasturage that could feed horses.

As the same time, the British military found itself penned up inside Boston, cut off from the town’s usual supply of food from the countryside.

It would take about six weeks before the government and merchants of London would hear of the outbreak of war, another six weeks before any supply ships they sent in response would arrive at Boston. The royal authorities therefore had to secure their own provisions for the next three months. Of course, that was a concern for Boston’s civilian authorities as well.

Leaders of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress saw the same situation. Recognizing that it was to their advantage to starve out the enemy, the committee of safety told farmers around the harbor not to sell provisions to anyone in the British military. Of course, that was easier said than done.

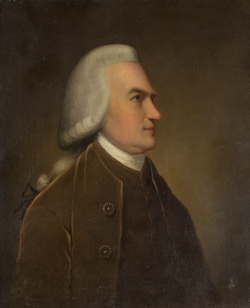

Boston selectman Oliver Wendell owned animals on Hog Island. “Greatly shocked by the Nervous Disorder,” he had left Boston for Newbury before the fighting broke out. His former apprentice Henry Prentiss therefore was trying to manage Wendell’s assets for him from Charlestown.

Of course, neither of those merchants actually handled the animals; that was the job of an employee named William Harris. On 9 May, Prentiss told Oliver Wendell, “Harris continues [on the] Island and sells to every one that comes.”

That wasn’t entirely voluntary. The next day, a man named Elijah Shaw told the committee of safety that British soldiers had “robbed him of 11 cows, 3 calves, a yearling heifer, 48 sheep, 61 lambs, 4 hogs, and poultry, hay 5 tons, and almost all his furniture.” The military was confiscating valuable provisions from people who wouldn’t sell.

On 12 May, Prentiss sent more details, starting with an inquiry from one of Wendell’s fellow selectmen, Thomas Marshall:

Coll. Marshall sent over here to know what Stock you had upon the Island, upon which I sent Mingo to the Island to bring an account to me.Mingo was enslaved to Wendell, it appears, and trusted by him. At the start of the month another mercantile partner, Nathaniel Appleton, reported that Mingo had just gotten out of besieged Boston and “will give you more particulars of the Town.” Then the man returned from Newbury to Charlestown, doing this job for Prentiss.

He tells me Mr. Harris is very uneasy, the people from the Men of War frequently go to the Island to Buy fresh Provision, his own safety obliges him to sell to them, on the other Hand the Committee of Safety have thretned if he sells anything to the Army or Navy, that they will take all the Cattle from the Island, & our folks tell him they shall handle him very rufly.