“The Measles coming into the Town”

It quoted extensively from the diary of the Rev. Dr. Cotton Mather, and I’ll quote from those extracts.

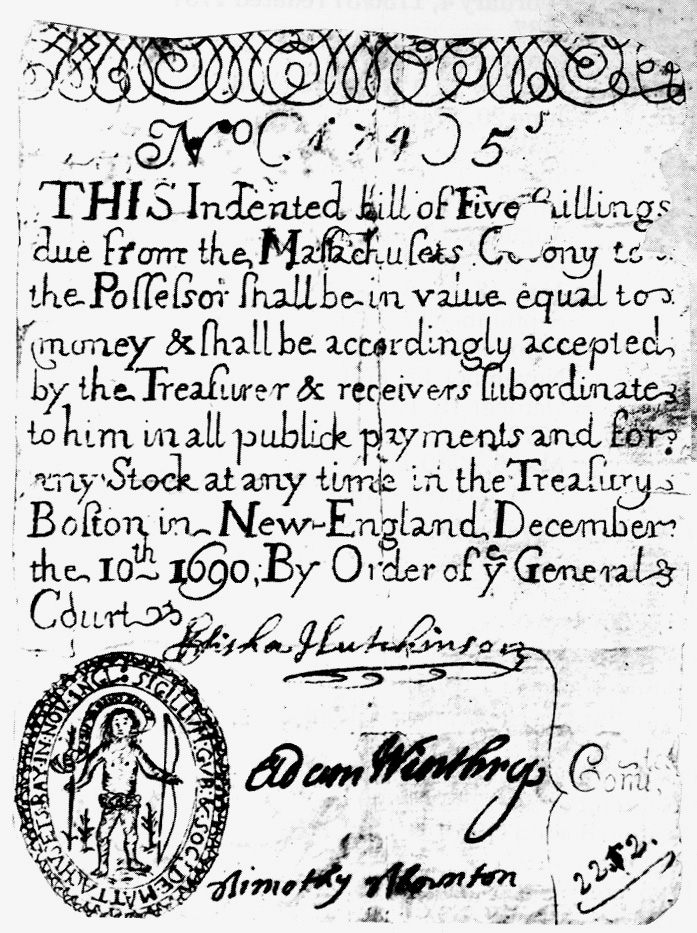

[18 Oct] …The Measles coming into the Town, it is likely to be a Time of Sickness…In 1757 Dr. Francis Home of Edinburgh determined that measles was caused by a pathogen. Unfortunately, he did this by using blood from one person with measles to infect others. He then tried to inoculate against the disease using the same technique as with smallpox, but measles doesn’t work the same way.

[24 Oct]… [in the past week] my Son Increase fell sick…

[27 Oct] My desirable Daughter Nibby, is now lying very sick of the Measles…

[30 Oct] This day, my Consort, for whom I was in much Distress, lest she should be arrested with the Measles which have proved fatal to Women that were with child, after too diligent an Attendance on her sick Family, was… surprized with her Travail [went into labor]… [and] graciously delivered her, of both a Son and a Daughter… wherein I receive numberless Favors of God. My dear Katy, is now also down with the Measles…

[1 Nov] Lord’s Day. This Day, I baptized my new-born twins… So I called them, ELEAZAR and MARTHA….

[4 Nov] In my poor Family, now, first, my Wife has the Measles appearing on her…

My Daughter Nancy is also full of them…

My Daughter Lizzy, is likewise full of them…

My Daughter Jerusha, droops and seems to have them appearing.

My Servant-maid, lies very full and ill of them.

[5 Nov] My little son Samuel is now full of the Measles….

[7 Nov]… my Consort is in a dangerous Condition, and can gett no rest... Death… is much feared for her… So, I humbled myself before the Lord, for my own Sins... that His wrath may be turned away…

[8 Nov] …this Day we are astonished, at the surprising Symptomes of death upon [my wife]… Oh! The sad Cup, which my Father has appointed me!... God enabled her to Committ herself into the Hands of a great and good Savior; yea, and to cast her Orphans there too…

I pray’d with her many Times, and left nothing undone…

[9 Nov] between three and four in the Afternoon, my dear, dear, dear Friend expired…. [I] cried to Heaven…

[10 Nov] …I am grievously tried, with the threatening Sickness of my discreet, pious, lovely Daughter Katharin.

And a Feavour which gives a violent Shock to the very Life of my dear pretty Jerusha.

[11 Nov] This day, I interr’d the earthly part of my dear consort…

[14 Nov] This Morning… the death of my Maid-servant, whose Measles passed into a malignant Feaver…

Oh! The trial, which I am this Day called unto in… the dying Circumstances of my dear little Jerusha!

The two Newborns, are languishing in the Arms of Death…

[15 Nov] … my little Jerusha. The dear little Creature lies in dying Circumstances. Tho’ I pray and cry to the Lord… Lord she is thine! Thy will be done!...

[18 Nov] …About Midnight, little Eleazar died.

[20 Nov] Little Martha died, about ten a clock, A.M.

I begg’d, I begg’d, that such a bitter Cup, as the Death of that lovely [Jerusha], might pass from me…

[21 Nov] …Betwixt 9 h. and 10 h. at night, my lovely Jerusha Expired. She was 2 years, and about 7 months old. Just before she died, she asked me to pray with her; which I did… and I gave her up unto the Lord. [Just as she died] she said, That she would go to Jesus Christ…

[23 Nov] …My poor Family is now left without any Infant in it, or any under seven Years of Age…

Not until 1963 did scientists develop an effective measles vaccine. In the first twenty years after the U.S. government tested and licensed that technique, it was estimated to have prevented 52,000,000 cases of the disease in this country. I was among the American children to benefit from the vaccine and never catch measles.

The World Health Organization reported that between 2000 and 2022, measles vaccination averted 57,000,000 deaths worldwide. That’s a huge number of people, about the population of Italy. But through a quirk of our brains, it can be more affecting to read about the series of small deaths, one after another, in Cotton Mather’s house in 1713.