“Hardships only make him firmer”

Joseph’s handbill read:

VERSESThis is a sample of “carrier verses.” It’s unusual in two ways. It makes no mention of current events, possibly because the politics of 1775 meant any comment would offend someone. And it specifies the name of the printer’s boy distributing it; though some other surviving examples did that, most didn’t.

Addressed by JOSEPH CREE,

To the

Gentlemen and Ladies,

To whom he carries the

NEW-YORK GAZETTEER.

January 1, 1775.

KIND SIRS, a young and bashful Boy,

Now comes, with Heart brimful of Joy,

To see, if you by some small Favor,

Will please t’encourage such a Shaver---

Though small, he has strove to do his Duty,

And hopes that he did always suit ye;

Through Frost and Snow and scorching Heat,

He has gone with News from Street to Street;

Without a Whimper or a Murmur,

For Hardships only make him firmer.

And now he thinks there’s some Pretence,

T’ obtain of you a few good Pence;

Or something that his Heart will cheer,

And make him merry this NEW-YEAR.

Cree family historian Gary L. Maher has stated that Joseph Cree was born in 1765, which would make him nine years old as he delivered those newspapers. If so, he probably didn’t write or set this verse himself, as some older printing apprentices did. The lines definitely emphasize how little he was.

However, Maher has also found a Joseph Cree enrolled in the New York militia in 1779, and a fourteen-year-old wouldn’t have been enrolled in the militia. So perhaps Joseph was older.

Cree started to work as a printer for Shepard Kollock’s New-Jersey Journal in Elizabeth, New Jersey, about 1783, the same year that Rivington gave up his newspaper in New York. Cree married a woman named Ann Crissey or Creesy, and they had children. City and county records show him living in Elizabeth in the 1790s.

While newspaper owners’ names appeared in their pages regularly, the employees who printed those pages usually remained anonymous. Cree’s name didn’t appear in any newspaper until the 18 Sept 1798 New-Jersey Journal:

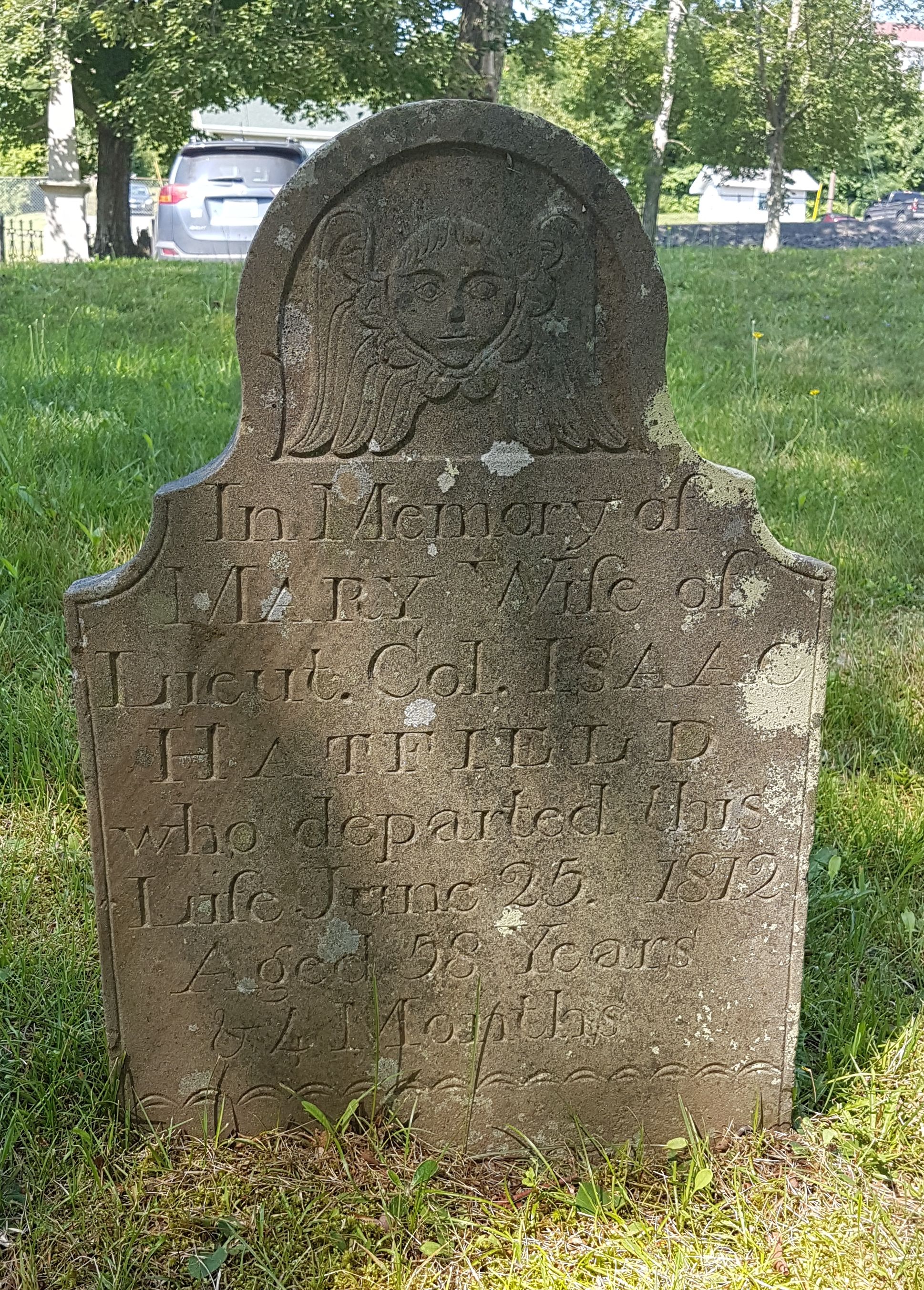

DIED.Cree was buried in the graveyard of Elizabeth’s First Presbyterian Church, twenty-three years after he passed out his greeting for the new year.

On Sunday night [16 September], in this town, of the yellow fever, which he caught in New-York, JOSEPH CREE, Printer, for fifteen years a journeyman with the Editor of this paper.—He has left a worthy woman and four small children to deplore his loss.