Thomas Jay McCahill Fellowships for 2026–27

The announcement says:

The McCahill Fellowship will provide up to $75,000 for a one-year period to support the cost of research, travel, housing and per diem expenses for one or more scholars to undertake advanced research on a topic germane to American history in the colonial and revolutionary periods. Fellows will have sustained access to collections and professional staff in a quiet study room at the American Revolution Institute’s headquarters, Anderson House, in Washington, D.C.The upcoming year’s McCahill fellow is Prof. Christine DeLucia of Williams College, writing on “Land, Diplomacy, and Power in the Revolutionary Northeast.”

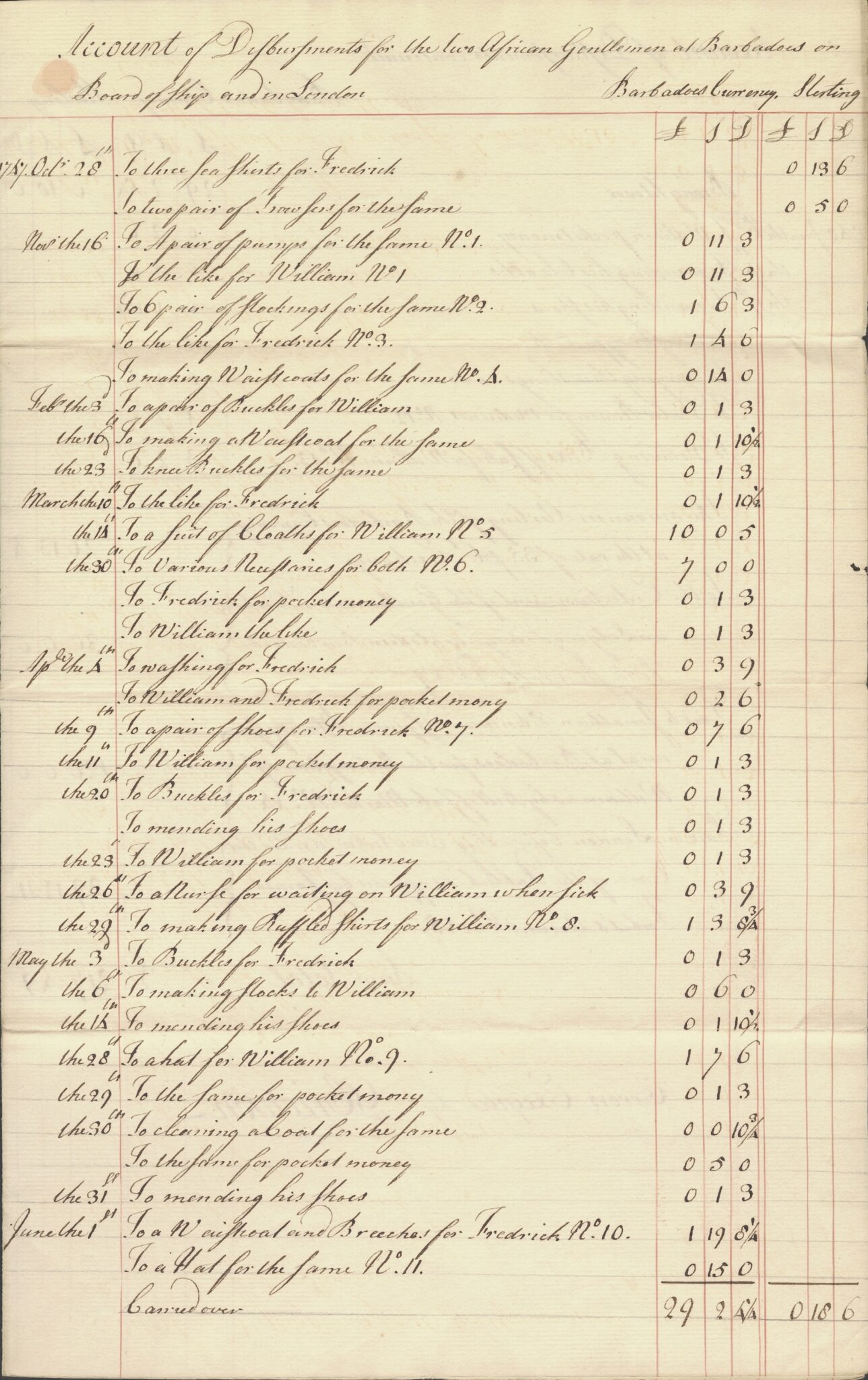

The McCahill Fellowship is open to graduate students and advanced and independent scholars who are conducting research that may benefit from various primary resources, with an emphasis on the collections of the American Revolution Institute and/or the American Independence Museum.

The McCahill Fellow’s research is expected to be on one or more of the following periods:Applicants should submit the following:

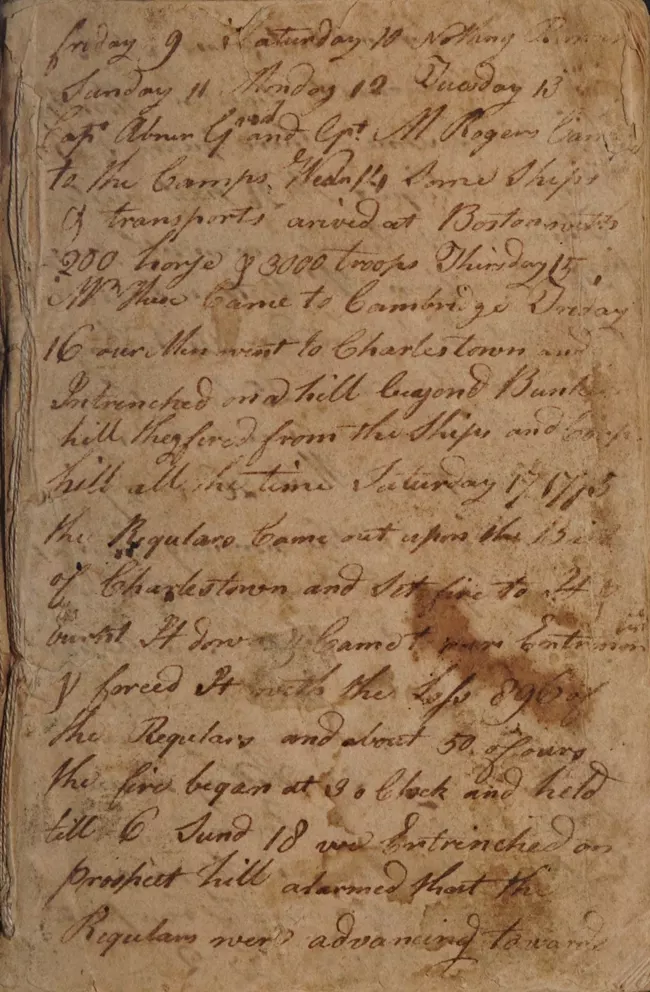

- the Revolutionary War

- colonial British America, preferably for research leading in some way to an issue of the revolutionary period

- the early American republic, preferably for research leading in some way to an issue of the revolutionary period.

The deadline for application is 31 October 2025. Applicants will be notified of the selection committee’s decision by the end of January 2026.

- Curriculum vitae, including educational background, publications and professional experience.

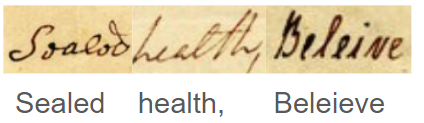

- Brief outline of the research proposed (not to exceed two pages), along with an expectation of how the fellow might use the research library and collections of the American Revolution Institute.

- Writing sample of 10-25 pages in the form of a published article, book excerpt, or paper submitted for course credit, which can be submitted in Word or P.D.F. format.

- Budget for proposed research project to include a schedule and related costs for housing and travel.

- For current graduate students only: Two confidential letters of recommendation from faculty or colleagues familiar with the applicant and his or her research project. Note: If letters are to be mailed independently, please include the names of recommenders when submitting the application.