How Did the Sons of Liberty Bowl Gain Its Name?

Yesterday I quoted from a report of an 1873 special meeting of the Massachusetts Historical Society where a member displayed the silver bowl that Nathaniel Barber had commissioned from Paul Revere one hundred and five years before.

That year the bowl came back to Boston after decades of being owned by a man in New York.

That same page in the M.H.S. Proceedings went on to say:

The name “Sons of Liberty” is said to have been adopted here from its having been used in a speech in Parliament by our friend Colonel [Isaac] Barré. The fellowship under the name here was formed after the passage of the Stamp Act, and was first called in a Boston paper “The Union Club.” It was composed mostly of mechanics, and held secret meetings, at which the risings and other measures were planned. The principal committee met in the counting-room of Chase & Speakman’s distillery, in Hanover Square.That report didn’t link the “Fifteen Associates” named on the bowl to the “Union Club” or “Sons of Liberty,” except in the general way that they were all on the same side of the pre-Revolutionary political divide.

Three years later, the Catalogue of the Loan Collection of Revolutionary Relics: Exhibited at the Old South Church described the same bowl this way:

Silver Bowl. For some years previous to the Revolution a number of gentlemen known as the ”Sons of Liberty” used to meet and discuss the questions of the day. In 1768, the Colonial Assembly of Massachusetts Bay voted to raise a Committee of Correspondence with her Sister Colonies on their grievances. The British Ministry demanded the repeal of this act. The Assembly voted “not to rescind,” and in commemoration of this vote the Sons of Liberty had this massive Punch Bowl made.That description thus presented the fifteen men listed on the bowl as “the ‘Sons of Liberty.’” Not just Sons of Liberty, but the Sons of Liberty.

In 1881 The Memorial History of Boston included Edward G. Porter’s chapter on “The Beginning of the Revolution.” That weighty history mashed together the “party of Boston mechanics” who organized the first anti-Stamp Act protest in 1765 (as named by the Rev. William Gordon) with “the Sons of Liberty” who used the silver punch bowl in 1768. In fact, they were two separate groups; not one name appears on both lists.

Other authors followed suit, soon calling it “the Sons of Liberty bowl.” And after the bowl came on the market in 1949, as described by Museum of Fine Arts curator Ethan Lasser, Arts Digest referred to it as “Paul Revere’s celebrated Sons of Liberty Punch Bowl, thought by some to rank third among American historical treasures, after the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.” [The phrase “by some” is doing a lot of work there.]

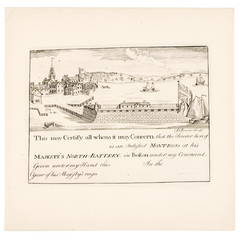

The current webpage for the artifact is titled “Sons of Liberty Bowl” and refers to “the Liberty Bowl.” The bowl does indeed have the words “Liberty” and “Librties,” and a picture of a Liberty Cap, inscribed on it. But the phrase “Sons of Liberty” was attached over a century later.

I agree that the fifteen men named on the bowl were Sons of Liberty as Boston used that term in the late 1760s. Nathaniel Barber and Daniel Malcom were particularly active in resisting royal officials. But they weren’t the only, the first, or the leading Sons of Liberty in town.

And this isn’t the only surviving punch bowl associated with Sons of Liberty in Boston, either. The Massachusetts Historical Society has a porcelain bowl owned by Benjamin Edes, one of the group Gordon credited for those anti-Stamp Act protests.