“The Colony of Connecticut must raise 6,000”

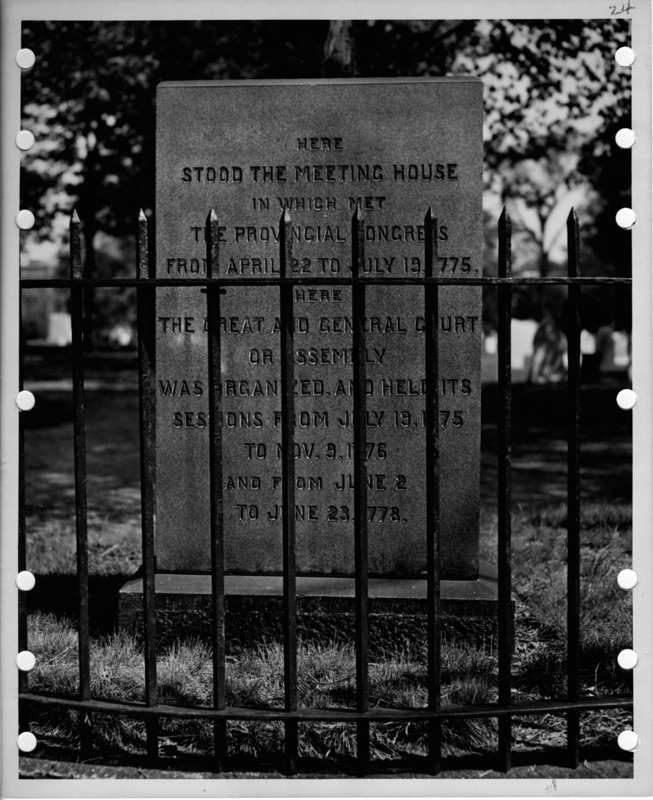

In this Journal of the American Revolution article from last year, I discussed how early in 1775 the congress had set up liaisons with the governments of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire in case war broke out.

The Massachusetts Patriots had alerted their colleagues in those colonies about the fighting on 19 April. And now they asked for troops.

In Connecticut, Gov. Jonathan Trumbull supported the Patriots. As soon as he heard the news from Lexington, he agreed to call the legislature into session to take official action. On 21 April, William Williams, the Connecticut assembly speaker and Trumbull’s son-in-law, wrote with two other politicians to the Massachusetts congress:

Every preparation is making to Support your Province— . . . the Ardour of Our People is such that they can’t be kept back;—The Colonels are to forward part of the best men & most Ready, as fast as possible; the remainder to be ready at a Moments warningSome militia officers were already on the move. Israel Putnam was in Concord on 21 April as the Massachusetts congress met. He wrote back:

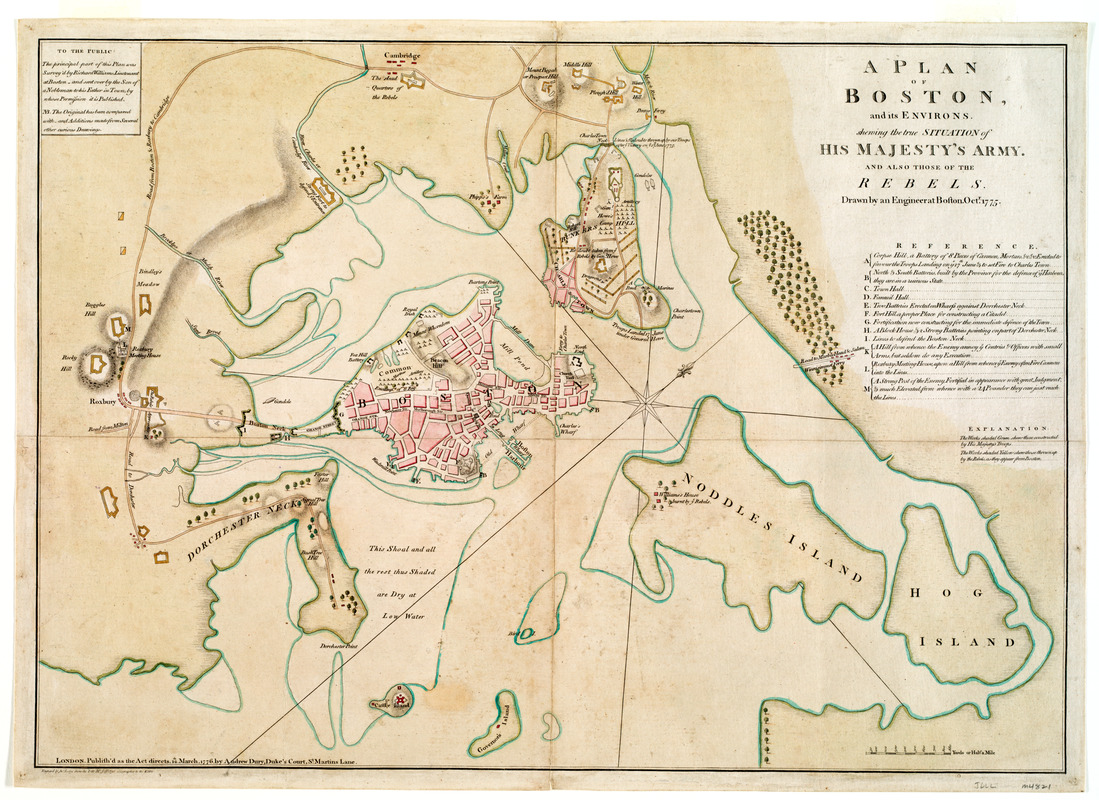

I have waited on the Committee of the Provincial Congress, and it is their Determination to have a standing Army of 22,000 men from the New-England Colonies, of which, it is supposed, the Colony of Connecticut must raise 6,000, and begs they would be at Cambridge as speedily as possible, with Conveniences; together with Provisions, and a Sufficiency of Ammunition for their own Use.Col. Benedict Arnold and his volunteers left New Haven on 22 April and arrived in Cambridge one week later. On 23 April a letter from Wethersfield to New York said:

We are all in motion here, and equipt from the Town, yesterday, one hundred young men, who cheerfully offered their service; twenty days provision, and sixty-four rounds, per man. They are all well armed, and in high spirits. . . . Our neighbouring Towns are all aiming and moving. Men of the first character and property shoulder their arms and march off for the field of action. We shall, by night, have several thousands from this Colony on their march. . . .On 27 April the Connecticut legislature voted to enlist 6,000 soldiers—six regiments of about a thousand men each. Joseph Spencer was appointed general of this army with Putnam next in seniority. (David Wooster remained in Connecticut to oversee defending its coast or New York as needed.)

We fix on our Standards and Drums, the Colony Arms, with the motto, “qui transtulit sustinet,” round it in letters of gold, which we construe thus: “God, who transplanted us hither, will support us.”

Notably, Connecticut asked men to enlist in its army only until 10 December, not the end of the year as other New England colonies did. That became a problem when December rolled around and lots of Connecticut companies wanted to leave early (as Gen. George Washington viewed it) or on time (as their enlistment papers said). I discussed that conflict back here.

TOMORROW: Rhode Island’s observers.