“To pass unmolested into the town of Boston”

- heard from Col. Benedict Arnold of Connecticut about artillery up along Lake Champlain.

- ordered Maj. Timothy Bigelow to move weapons from Worcester to the siege lines.

- hired an express rider.

- urged its subcommittee of Azor Orne, Richard Devens, and Benjamin White to “form a plan for the liberation of the inhabitants” of Boston now that Gen. Thomas Gage was allowing them to leave.

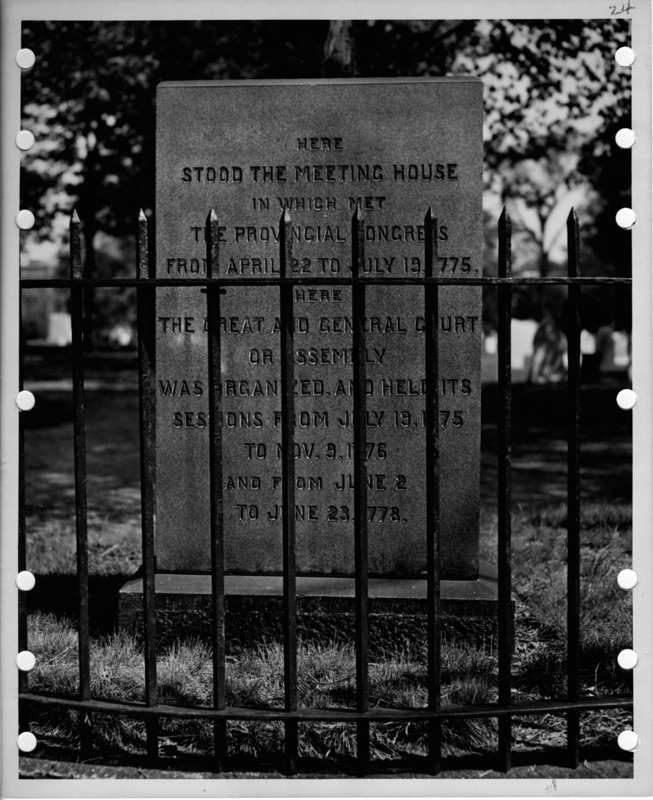

Probably after being stung by the letter from the Massachusetts Provincial Congress quoted yesterday, the committee appointed its chair, Dr. Joseph Warren, along with Joseph Palmer and Orne, to take their resolution out to that body in Watertown.

The committee’s recommendation was:

Whereas, proposals have been made by General Gage to the inhabitants of the town of Boston, for the removal of their persons and effects into the country, excepting their arms and ammunition:Dr. Warren signed that report “clerk pro tem.,” indicating he had taken on yet another job.

Resolved, that any of the inhabitants of this colony, who may incline to go into the town of Boston with their effects, fire-arms and ammunition excepted, have toleration for that purpose, and that they be protected from any injury or insult whatsoever. This resolve to be immediately published.

The following orders were delivered to Col. Samuel Gerrish:You are hereby empowered, agreeably to a vote of the Provincial Congress, to grant liberty, that any of the inhabitants of this colony, who may incline to go into Boston with their effects, fire-arms and ammunition excepted, have toleration for that purpose; and that they be protected from any injury or insult whatsoever, in their removal to Boston.

The following form of a permit is for your government, the blanks in which you are to fill up with the names and number of the persons, viz.:Permit A. B., the bearer hereof, with his family, consisting of persons, with his effects, fire-arms and ammunition excepted, to pass unmolested into the town of Boston, between sunrise and sunset. By order of the Provincial Congress.

The committee of safety addressed only the question of how to reciprocate to Gen. Gage’s decision and let Loyalists enter Boston. It left the bigger question of how to help refugees who had left their homes in that town up to the congress.

The provincial congress made some amendments to the committee’s recommendation, so this is what went out officially:

In PROVINCIAL CONGRESS, Watertown, April 30, 1775.The congress delegates, having given up their whole Sunday waiting for the committee, then adjourned for the day.

Whereas an agreement has been made between General Gage and the inhabitants of the city of Boston, for the removal of the persons and effects of such of the inhabitants of the town of Boston, as may be so disposed, excepting their fire arms and ammunitions into the country:

RESOLVED, That any of the inhabitants of this colony, who may incline to go into the town of Boston with their effects, Fire-Arms and Amunitions excepted, have toleration for that purpose; and that they be protected from any injury and insult whatsoever, in their removal to Boston, and that this resolve be immediately published.

P. S. Officers are appointed for the giving permits for the above purposes; one at the sign of the Sun at Charlestown, and another at the house of Mr. John Greaton, jun. at Roxbury.

Ordered, That attested copies of the foregoing resolve be forthwith posted up at Roxbury, Charlestown and Cambridge.

Resolved, That the resolution of Congress, relative to the removal of the inhabitants of Boston, be authenticated, and sent to the selectmen of Boston, immediately, to be communicated to general Gage, and also be published in the Worcester and Salem papers.

Ordered, That Doct. Taylor, Mr. Bailey, Mr. Lothrop, Mr. Holmes and Col. Farley, be a committee to consider what steps are necessary to be taken for the assisting the poor of Boston in moving out with their effects to bring in a resolve for that purpose; and to sit forthwith.

By the time the congress’s resolve was published in the 3 May Massachusetts Spy, the Rev. John Murray had stepped down as its president pro tempore and James Warren of Plymouth had declined the post. So the resolution was published over the name of the new president pro tem., Dr. Joseph Warren. As if he didn’t already have plenty to do.

TOMORROW: Spreading out the refugees.