The Last of the Last Royal Governor of New Hampshire

They loaded over a hundred barrels of gunpowder into a flat-bottomed boat. Just before embarking, they released John Cochran, commander of the fort, and his wife Sarah from confinement in their house.

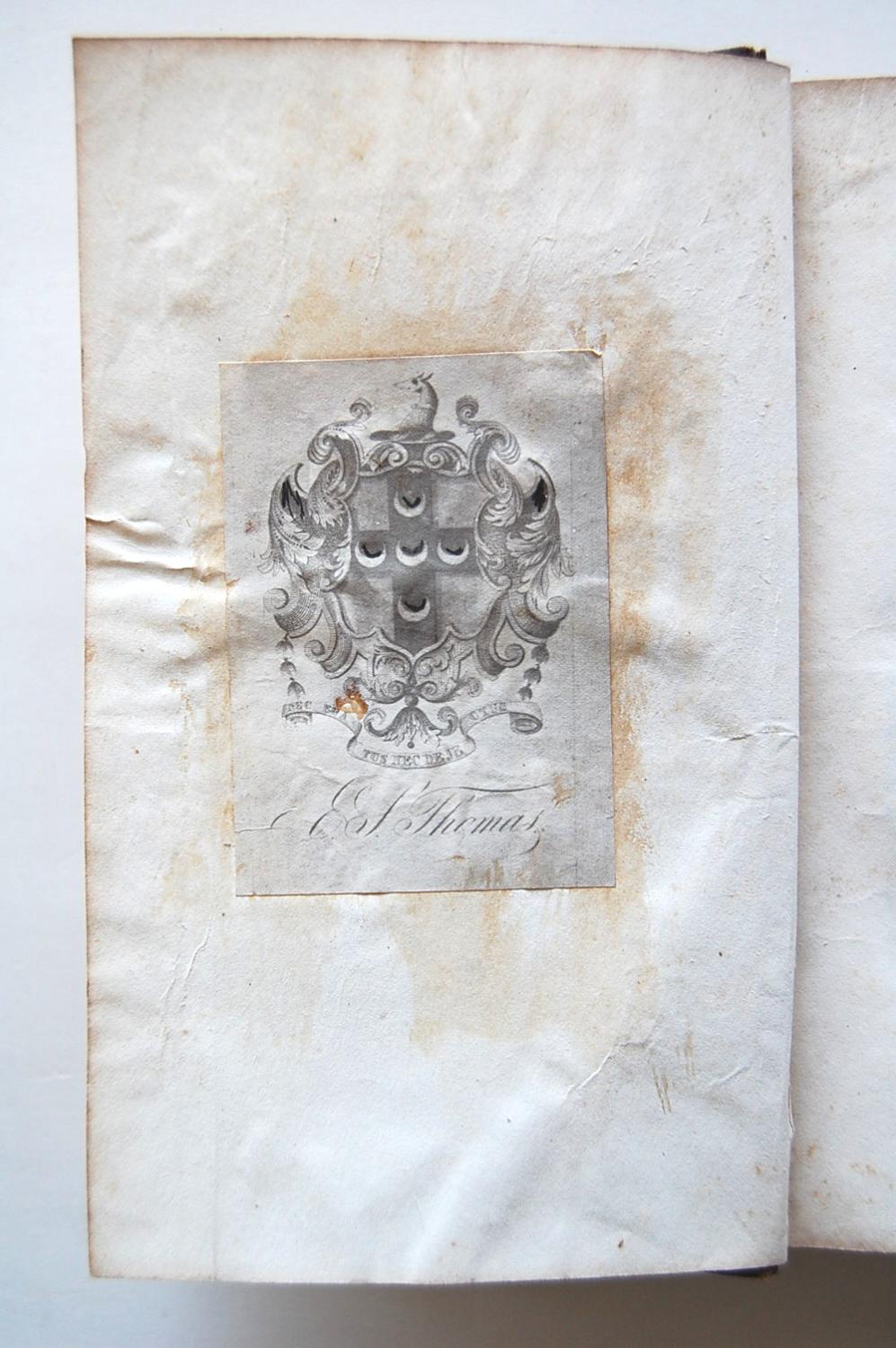

But first they told Cochran to “go and take care of the Powder they had left.” As he reported that evening to Gov. John Wentworth (shown here), the raiders had left “one barrel.”

The royal governor lost most of his authority that day. He couldn’t even get men to row him out to the fort on his official barge.

Wentworth soon knew the identities of many of the raiders, but he didn’t foresee prosecuting them. “No jail would hold them long, and no jury would find them guilty,” he wrote. The most he could do was fire them from their appointed positions.

H.M.S. Canceaux and H.M.S. Scarborough arrived in Portsmouth harbor over the next week, preventing further attacks. The result was a stalemate, with the Patriots leaving Gov. Wentworth alone as long as they could proceed with their plans.

Those activists had already called a province-wide meeting in July 1774 to send delegates to the First Continental Congress. They did that again in January 1775 for the Second Continental Congress. Another meeting in late April endorsed the New Hampshire militia companies already heading toward Boston.

Gov. Wentworth convened the official New Hampshire legislature on 4 May 1775, then prorogued it. He tried to make peace between Capt. Andrew Barkley on the Scarborough, who was seizing supplies and sailors from ships, and the Patriot militiamen, now fortifying Portsmouth harbor against attack from the water.

On 13 June, Wentworth offered shelter to John Fenton, a retired British army captain and a New Hampshire militia colonel. A crowd gathered outside his mansion, pointing a cannon at the front door. Fenton gave himself up. The governor and his wife fled out the back, carrying their infant son.

The Wentworths took refuge at Fort William and Mary, still commanded by John Cochran. The governor reported, “This fort although containing upward of sixty pieces of Cannon is without men or ammunition,” but it was protected by the Scarborough.

Wentworth continued to try to exercise gubernatorial authority, sending messages to the provincial assembly as if he were in his mansion nearby rather than on an island in the harbor. The legislature ignored him and his declarations that their session was adjourned.

Soon it became clear that there was no point in staying in New Hampshire. Capt. John Linzee and H.M.S. Falcon arrived to carry away the fort’s remaining cannon and keep them out of rebel hands. On 23 August the Wentworths boarded a warship to sail to besieged Boston.

With Gov. Wentworth went John Cochran, commander of Fort William and Mary.

Cochran’s wife Sarah and their children weren’t in the fort that summer, however. They were on the family farm in Londonderry.

TOMORROW: A Loyalist family’s troubles.