The Plain Language of the Alien Enemies Act

The Naturalization Law made it harder for immigrants to become citizens of the U.S. of A. by increasing the number of years a person had to live in the country before applying. This was repealed in 1802.

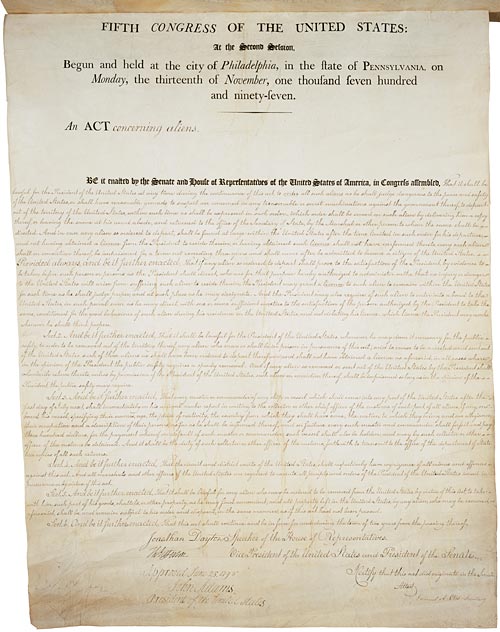

The Act Concerning Aliens (distinguished as the Alien Friends Act) empowered the President to jail or deport any non-citizen who he determined was “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States.” This expired after two years.

The Sedition Act criminalized combining to oppose government measures and criticizing the U.S. government, House, Senate, or President. The John Adams administration deployed this law against Jeffersonian politicians and printers. It expired in 1800.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were strongly opposed at the time. They led to Jeffersonian victories over Federalists. Since then, historians and legal scholars have almost universally treated these laws as a Bad Thing.

The fourth of those laws from 1798 remained on the books, however: the Act Respecting Alien Enemies. It didn’t have an expiration date. Instead, its language limits the circumstances under which a President can invoke it.

The Alien Enemies Act empowers a President to act only

whenever there shall be a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion shall be perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States, by any foreign nation or governmentIf “any foreign nation or government” is in a “declared war” with the U.S. of A. or has made a “predatory incursion,” then the federal government can jail and deport that country’s male citizens aged fourteen or older. The U.S. Constitution further vests the power to declare war in Congress, not the executive branch.

Last week the White House illegally invoked the Alien Enemies Act to justify deporting hundreds of Venezuelans to El Salvador even though there’s no declared war against Venezuela nor any invasion by Venezuela.

In place of the law’s actual conditions, the White House claimed that the Tren de Aragua criminal gang and Venezuela amount to something it calls “a hybrid criminal state.” (It didn’t address how in 2023 the Venezuelan government deployed 11,000 soldiers to break up a Tren de Aragua stronghold.) The White House also claims that illegal migration by individuals, in unspecified numbers, is the equivalent of a government-led invasion.

In some ways, the President is an expert on criminal states. He’s a convicted felon, facing additional federal and state charges, adjudicated as liable for sexual assault, and bound by multiple legal settlements for fraud. But that experience in crime doesn’t give this President the legal power to invoke a statute contrary to its provisions.

The executive branch then further demonstrated its lawlessness by ignoring a judicial order to stop flying people out of the country until the legal issues can be decided.

The Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela shows the danger of allowing a coup plotter—in this case, Maduro’s predecessor Hugo Chávez after 1992—to take political office. Coup plotters by definition don’t respect elections and the rule of law. Venezuela is now only nominally republican, actually authoritarian (as is El Salvador). But Venezuela isn’t in declared war against or invading the U.S. of A., as the Alien Enemies Act stipulates. It’s not the only criminal state in this story.