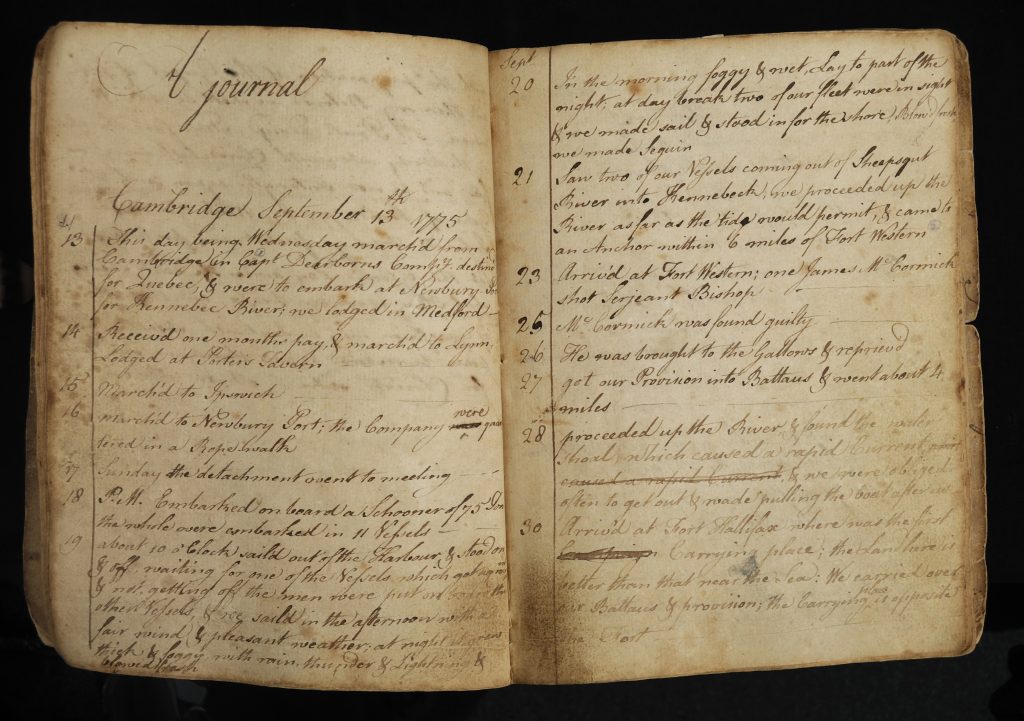

Now it’s true that at one point

Benjamin Franklin suggested that the turkey, rather than the bald or American eagle, should be the emblem of the new nation.

But Franklin didn’t make that remark in 1776 during the earliest

discussions of the U.S. national seal. He wrote that in January 1784 after learning about the public debate over the

Society of the Cincinnati, the new hereditary organization of

Continental Army officers and their male heirs.

Still the U.S.

minister to

France,

Franklin wrote to his daughter

Sarah Bache (

pronounced “Beach”):

I received by Captn. Barney those relating to the Cincinnati. My opinion of the institution cannot be of much importance. I only wonder that when the united wisdom of our nation had, in the Articles of Confederation, manifested their dislike of establishing ranks of nobility, by authority either of the Congress or of any particular state, a number of private persons should think proper to distinguish themselves and their posterity, from their fellow citizens, and form an order of hereditary Knights, in direct opposition to the solemnly declared sense of their country.

In interpreting this letter, it’s useful to recognize how Franklin handled it. Yes, he addressed his daughter and kept the tone folksy. But he rarely discussed politics with Sarah Bache, and this letter didn’t include any personal news that she would presumably want to hear. He was simply using the form of a family letter to get some political thoughts off his chest.

Even more significantly, Franklin actually never sent this letter to his daughter. Instead, in the spring of 1784 he shared it with a couple of French friends, the abbé

André Morellet and the

comte de Mirabeau. He also continued to revise the text.

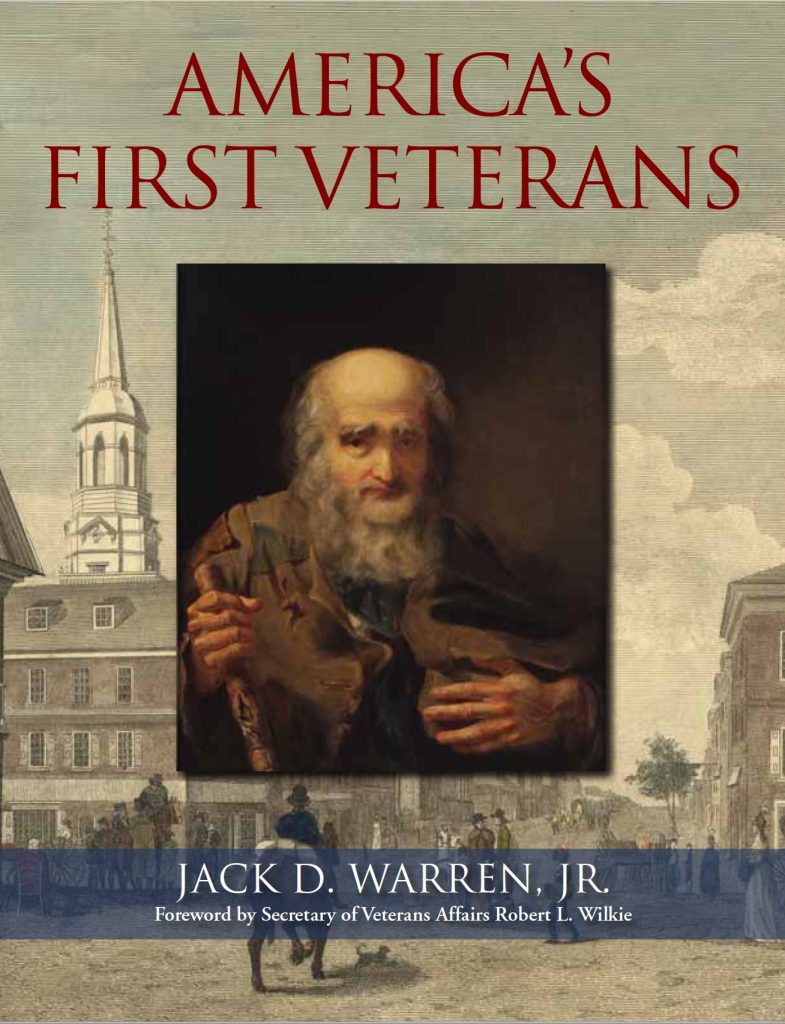

All three men appear to have agreed that it would be impolitic for Franklin to publicize his views of the Cincinnati under his own name. Instead, Mirabeau quoted portions of the letter without attribution later that year in a London pamphlet titled

Considérations sur l’ordre de Cincinnatus, ou imitation d’un pamphlet anglo-américain. Morellet published a complete French translation after Franklin’s death in 1790. (The Society of the Cincinnati included a French branch as well as one for each of the thirteen states, so French noblemen knew about the debate.)

Franklin’s whole letter didn’t appear in English until his grandson

William Temple Franklin published a collection of writings in 1817. By then the founding of the Cincinnati was no longer a burning political issue. The comments about the national emblem were more striking, even if Franklin had originally drafted them to make sarcastic points about a particular issue:

Others object to the bald eagle [of the Cincinnati medal, example show above], as looking too much like a Dindon or turkey. For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character. He does not get his living honestly.

You may have seen him perched on some dead tree, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labour of the fishing hawk; and when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish, and is bearing it to his nest for the support of his mate and young ones, the bald eagle pursues him, and takes it from him. With all this injustice, he is never in good case, but like those among men who live by sharping and robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank coward: the little king bird not bigger than a sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district.

He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America, who have driven all the king birds from our country, though exactly fit for that order of knights which the French call Chevaliers d’Industrie [i.e., “knights of the road”]. I am on this account not displeased that the figure is not known as a bald eagle, but looks more like a turkey.

For in truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours, the first of the species seen in Europe being brought to France by the Jesuits from Canada, and served up at the wedding table of Charles the ninth. He is besides, (though a little vain and silly tis true, but not the worse emblem for that) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.

(Ironically, that American emblem the turkey was named after a European country, either because Turkish merchants sold New World turkeys in early modern Europe or because sixteenth-century Englishman conflated turkeys with guinea fowl that Turkish merchants imported from Africa.)

The musical

1776 therefore has a slight foundation for portraying Benjamin Franklin in the song “The Egg” as wanting the turkey to be the U.S. of A.’s national bird.

However, as I

discussed yesterday, there’s no evidence for

John Adams championing the eagle, as in that song. And I’ve found no evidence for

Thomas Jefferson suggesting that the national symbol should be a dove.

The whole debate in “The Egg” was a last-minute creation of songwriter Sherman Edwards. During the tryouts of

1776 in New Haven, Edwards and his colleagues decided the show needed a light-hearted number in the second act. The musical’s poster,

designed by Fay Gage, showed a patriotic eagle hatching. With the inspiration of that art and Franklin’s 1784 letter, Edwards imagined his lead characters arguing over the national bird.

And a few years later, I watched that scene as an impressionable schoolboy and assumed it had some solid basis in fact. Another Bicentennial

myth shattered!