“Permission to pass to & repass from Noddle’s Island”

According to Mellen Chamberlain’s Documentary History of Chelsea, Williams’s “most profitable business had been supplying the King’s troops rendezvoused at Boston, in time of war, and merchant vessels, in time of peace, with fresh provisions from his fields and stock yards.”

That tie to the royal establishment and imperial trade was probably why Williams had signed a complimentary address to Gov. Thomas Hutchinson on his departure for London in June 1774, which quickly became a litmus test for Loyalism.

On the other hand, Williams also had strong ties to the other side of the political divide. He was the son of Roxbury farmer Joseph Williams, and I found hints that that family helped to smuggle cannon out of army-occupied Boston in 1774–75. Williams’s sisters married into Patriot families like the Mays, Heaths, and Daweses. His brother Samuel had moved out to Warwick but then came back east as a Provincial Congress delegate and militia captain.

On 21 April, Williams was in Boston and ran into William Burbeck, who held the Massachusetts government post of storekeeper at Castle William. A year later Burbeck described their interaction:

after some Conoversation with him setting forth my Concern how I should git out of town, Expecting every minute that I should be sent for; to go Down to that Castle—Days after arriving behind provincial lines, Burbeck became the second-in-command of the Massachusetts artillery regiment.

he told me that he would Carry me over to Noddles Island if I would Resque it that he would Do the same for ye good of his Country; And am Sure that if we had been taken Crossing of water must have been confind. to this Day, or otherway more severly punished. . . . And that the Very next morning after; A party of men & Boat was sent after me And Serchd. my house & Shop to find me—

that after we got to ye Island Mr. Williams ordered one of his men to Carry me over to Chelsea by which means I am now in Cambridge—And that a few Days after I got into Cambridge sent to Mr. Williams Desiring him to Send my millitary Books & plans as also all my instruments which ye Army stood in great Need of. And Could not Do without.

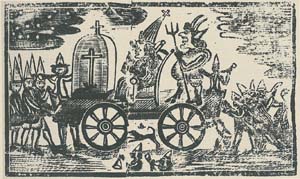

However much Williams wanted to support the Patriot cause, the British military still controlled Boston harbor. So he also made a deal with the royal authorities. On 1 May, Capt. Robert Donkin, one of Gen. Thomas Gage’s aides, issued Williams a pass, shown above courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Head Qrs. Boston 1st. May 1775Adm. Samuel Graves approved this pass as well. After all, the Royal Navy had at least one storehouse on Noddle’s Island, including a cooper’s shop.

The Bearer, Mr. Williams, has the Commander in Chief’s permission to pass to & repass from Noddle’s Island to this place as often as he has occasion; he having given security to carry no people from hence, or bring any thing off the Island without leave from His Excelly or the Admiral—

Rt. Donkin

Aide Camp

NB. his own Servants row him.