John Pigeon (1725-1800) was a prominent Boston merchant specializing in dry goods, meaning cloth and

clothing.

Pigeon married Jane Dumaresq, from a wealthy Huguenot family, in 1752. He was an Anglican, a warden of

Christ Church in the North End.

In the 1750s Pigeon ran notices in the

Boston News-Letter and

Boston Evening-Post announcing what people could buy “At his Shop near Doctor [John] Clark’s” on Fish Street in the North End. These were long advertisements in small (italic) type listing a broad assortment of cloths with now-unfamiliar names, subtle variations on types of handkerchiefs, and garments of many sorts.

As was typical at the time, Pigeon didn’t confine himself to one line. He also offered “Cheshire cheese, starch, best London pipes,…Philadelphia flour, rice, English west-india rum, New-England cheese, indigo, sugars, cocoa, coffee, whale-bone and turpentine.”

In 1762 Pigeon shifted his business. The 25 October

Evening-Post stated:

This is to give Public Notice, That the Underwriters at Mr. John Welsh’s Insurance Office, North-End of Boston, have removed a little further to the Northward, to a New Insurance Office, just opened by Mr. John Pigeon, where he lately kept Shop; and where constant Attendance will be given by said Pigeon, to any Gentleman that will favour him with their Business, and the Business transacted with the greatest Dispatch and Fidelity.

Going into the insurance business didn’t mean Pigeon got out of shopkeeping entirely, however. On 18 Feb 1765 he advertised that “At the Insurance-Office in Fish-Street” people could buy “A small Parcel of choice CYDER, Anchors, Deck and Sheathing Nails, and English GOODS at the cheapest Rate.” On 30 September he offered a schooner, “80 or 90 Tons, nine Months old”; a sloop; salt; fish; anchors; and shoes, as well as those “English GOODS.”

Pigeon showed other signs of prosperity, admirable and regrettable. He was elected one of Boston’s wardens, responsible for enforcing the Sabbath. He was also a

slave owner. In 1753 his servants Manuel and Dinah got married. In 1763 Pigeon advertised for the return of another slave named Zangoe, “a middling sized Fellow, about 28 Years old, speaks broken

English, but can talk pretty good

French.”

Because Pigeon sold so many things, possibly on behalf of others, it’s not clear whether the “convenient Dwelling House with a Shop” that he offered on 29 Sept 1766 was his own. That property came with “a good large Yard and Garden, a Barn, Warehouse and Wharf, situate in Boston, near the Hay-Market,” plus three people, “Two Negro Men and one Negro Woman.”

By 1768, Pigeon had moved out to

Newton. In May he asked readers of the

Boston News-Letter and

Boston Chronicle to alert him to any debts he still owed through “Mr.

Nathaniel Barber, at the Insurance Office.” He was by then “but seldom in Boston.” Pigeon had retired to the life of a country gentleman.

Pigeon bought a house and land in Newton in 1769, then 60 acres and another house in 1770, and the house shown above in 1773. It’s possible he was moving around, but he also had two young sons—Henry and John, Jr.—to set up eventually. So maybe those other properties were meant for them.

Newton had no Anglican church for the family. The Pigeons took in

John Marrett (1741-1813), a 1763 graduate of

Harvard College, probably as a tutor for those boys. After trying for other pulpits, Marrett was installed in 1773 at the

Woburn parish that became

Burlington. He was a Congregationalist, and it seems significant that John Pigeon, Jr., went to the Presbyterian college at

Princeton in May 1773 rather than Harvard, which was closer and more welcoming for Anglicans.

In January 1774, Newton’s

town meeting named John Pigeon to its new committee of correspondence, headed by

Edward Durant. That September, Pigeon chaired the committee to instruct the town’s representatives to the

Massachusetts General Court, including Durant. He joined those men in the first

Massachusetts Provincial Congress the following month.

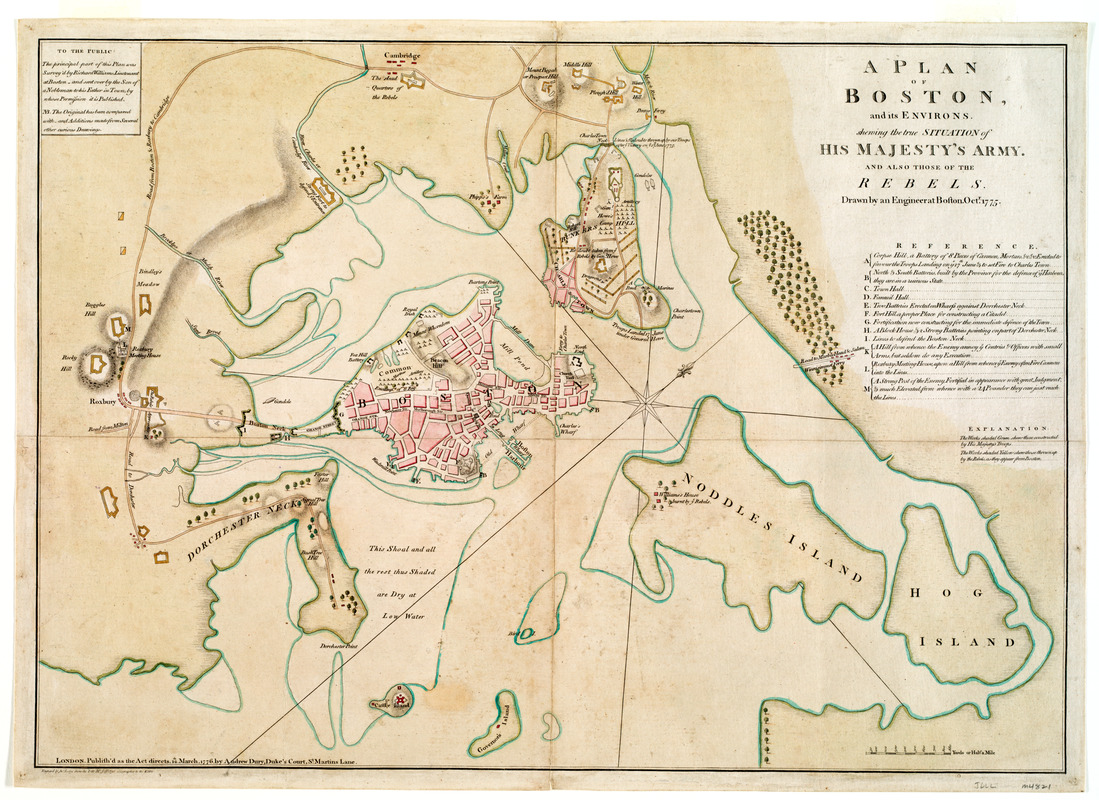

At the congress, one of Pigeon’s committee assignments was assessing the financial losses caused by the

Boston Port Bill. His familiarity with Boston business suited him for that. On 29 October, he was also elected to the congress’s crucial committee of safety. Four days later, at that committee’s first meeting, he was chosen clerk. That put John Pigeon right in the middle of Massachusetts’s preparations for war.

TOMORROW: Pigeon as commissary.