Johnny Tremain on the Screen and the Page

In the next week some North End institutions will celebrate the cultural heritage of that book.

Friday, 12 September, 7 to 9:30 P.M.

A Revolutionary Movie Night

Christopher Columbus Park

Join the Paul Revere House and the Friends of Christopher Columbus Park for a free movie night in honor of the 250th anniversary of Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride. Come meet Paul Revere, enjoy 18th-century tunes on the Fife and Drum, and then watch an outdoor screening of Thomas Edison’s silent short movie “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” followed by the iconic Disney classic Johnny Tremain. Popcorn will be provided by Joe’s Waterfront; bring your own seating for the lawn.

Wednesday, 17 September, 7 to 8:30 P.M.

Book Chat: Johnny Tremain with Patrick O’Brien

On Zoom through Old North Illuminated

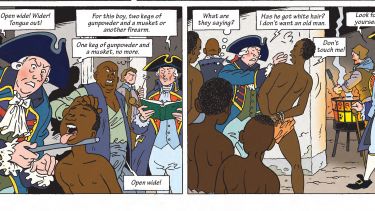

Written in 1943 by Esther Forbes, Johnny Tremain is among the best-selling children’s books of the 20th century. Intended for middle schoolers, the novel’s protagonist is 14-year-old Johnny Tremain, an apprentice silversmith working in Boston in the 1770s. When Johnny’s dreams of becoming a silversmith are dashed by a tragic accident, he takes a new job as a horse-boy, riding for the patriotic newspaper the Boston Observer and as a messenger for the Sons of Liberty. Soon, Johnny is involved in the pivotal events of the American Revolution, from the Boston Tea Party to the first shots fired at Lexington, while he encounters historical figures like John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and Dr. Joseph Warren. The book won the 1944 Newbery Medal and was adapted as a Disney film in 1957.

Patrick O’Brien, a history professor at the University of Tampa, will deliver a short presentation on the historical context surrounding the novel and then lead a discussion exploring themes from the book and what it means today as we approach America’s 250th anniversary. The discussion will be kind of like a virtual book club! This event is perfect for anyone who remembers reading Johnny Tremain as a child and for teachers and educators who would like to teach this novel with their students.

Register for this online discussion here while making a donation to Old North Illuminated for any amount. You’ll receive a Zoom link for the event.

Here are a couple of observations of my own. First, Johnny Tremain is certainly accessible to middle-school readers, and it won the Newbery Medal for best children’s book of the year. However, it was explicitly published as “A Novel for Old & Young.” That line has been dropped from the title page of more recent editions. [I have three copies of the book, in case you wonder.]

I don’t recall how it happened, but Johnny Tremain came up in my online talk for Old North Illuminated back in June. At the end of the novel the newly independent Johnny learns that his father was a Frenchman, and he experiences an emotional reconciliation with his departing Loyalist “cousin” even though her father cheated him. Symbolically, I observed, Forbes was bringing together American, French, and British—right in the middle of World War 2.

As for the movie, it’s definitely the “Disney version” of the novel. It made Johnny more admirable at the outset and his injury less long-lasting. It focused on rousing group politics and left out the deaths of some major characters. The movie also falls neatly into two halves because it was produced to be two episodes of The Wonderful World of Disney, though the studio did give it a cinema release. Folks can enjoy the movie for nostalgia, but shouldn’t miss out on the greater depth of the novel.

Here are more of my ramblings over the years on Johnny Tremain, the book (mostly) and the movie.

_-_Worcester_Art_Museum_-_IMG_7686.JPG/640px-The_Savage_Family%2C_circa_1779%2C_by_Edward_Savage_(1761-1817)_-_Worcester_Art_Museum_-_IMG_7686.JPG)