“When forty-two countrymen Sure bid their friends adieu.”

Ezra Lunt and Henry-Walter Tinges printed the Essex Journal in Newburyport with the financial backing of Isaiah Thomas, who made a hasty move from Boston to Worcester in April 1775.

On 26 May, the Essex Journal published this verse in a section of the back page titled “The Parnassian Packet”:

Seven Danvers men were killed in and around Jason Russell’s house in Menotomy, so that town got the next mention—which the newspaper’s Essex County audience probably appreciated.

Eventually the poet got to individuals, naming a couple of men at the top of society—Capt. James Miles of Concord and Isaac Gardiner, Esq., of Brookline—and Benjamin Pierce of Salem, also killed at the Russell House. Other dead officers went unnamed, however.

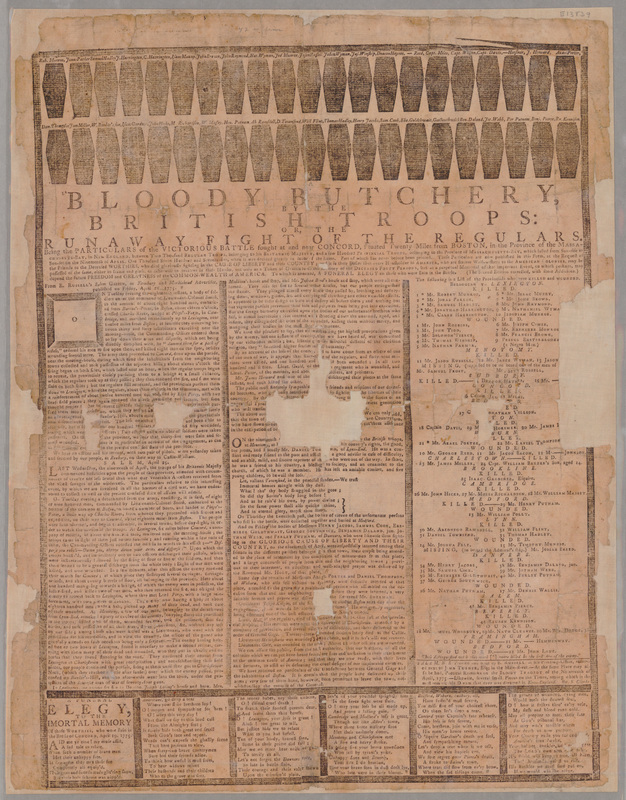

Ezekiel Russell printed this poem at the bottom of his “Bloody Butchery of the British Troops” broadside, shown above. You can peruse that page more closely through the American Antiquarian Society, founded by Thomas.

The Russell broadside contained some errors (a missing “brave,” “young” became “your,” another “your” dropped out), suggesting that shop hastily copied the text out of the newspaper. I would have expected the transmission to go the other way: from the Russell print shop, which was known for publishing a young woman’s elegiac verses, to the Essex Journal.

That in turn suggests that Russell didn’t issue the “Bloody Butchery” broadside until more than a month after the battle. Maybe he needed that time to engrave all those coffins.

On 26 May, the Essex Journal published this verse in a section of the back page titled “The Parnassian Packet”:

A Funeral ELEGY, to the Immortal Memory of those Worthies, who were slain in the Battle of CONCORD, April 19, 1775.This tribute to the local men killed the previous month started with the town of Lexington, not just because redcoats had fired the first fatal shots there but because that town lost more men than any other.

AID me ye nine! my muse assist,

A sad tale to relate,

When such a number of brave men

Met their unhappy fate.

At Lexington they met their foe

Completely all equip’d,

Their guns and swords made glitt’ring show,

But their base scheme was nipp’d.

Americans, go drop a tear

Where your slain brethren lay!

O! mourn and sympathize for them!

O! weep this very day!

What shall we say to this loud call

From the Almighty sent;

It surely bids both great and small

Seek GOD’s face and repent.

Words can’t express the ghastly scene

That here presents to view,

When forty-two brave countrymen

Sure bid their friends adieu.

To think how awful it must seem,

To hear widows relent

Their husbands and their children

Who to the grave was sent.

The tender babes, nay those unborn,

O! dismal cruel death!

To snatch their fondest parents dear,

And leave them thus bereft.

O! Lexington, your loss is great!

Alas! too great to tell,

But justice bids me to relate

What to you has befell.

Ten of your hardy, bravest sons,

Some in their prime did fall;

May we no more hear noise of guns

To terrify us all.

Let’s not forget the Danvers race

So late in battle slain,

Their courage and their valor shown

Upon the crimson’d plain.

Sev’n of your youthful sprightly sons

In the fierce fight were slain,

O! may your loss be all made up,

And prove a lasting gain.

Cambridge and Medford’s loss is great,

Though not like Acton’s town,

Where three fierce military sons

Met their untimely doom.

Menotomy and Charlestown met

A sore and heavy stroke,

In losing five young brave townsmen

Who fell by tyrant’s yoke.

Unhappy Lynn and Beverly,

Your loss I do bemoan,

Five of your brave sons in dust doth lye,

Who late were in their bloom.

Bedford, Woburn, Sudbury, all,

Have suffer’d most severe,

You miss five of your choicest chore,

On them let’s drop a tear.

Concord your Captain’s fate rehearse,

His loss is felt severe,

Come, brethren, join with me in verse,

His mem’ry hence revere.

O ’Squire Gardiner’s death we feel,

And sympathizing mourn,

Let’s drop a tear when it we tell,

And view his hapless urn.

We sore regret poor Pierce’s death,

A stroke to Salem’s town,

Where tears did flow from ev’ry brow,

When the sad tidings come.

The groans of wounded, dying men,

Would melt the stoutest soul,

O! how it strikes thro’ ev’ry vein.

My flesh and blood runs cold.

May all prepare to meet their fate

At GOD’s tribunal bar,

And may war’s terrible alarm

For death us now prepare.

Your country calls you far and near,

America’s sons ’wake,

Your helmet, buckler, and your spear,

The LORD’s own arm now take

His shield will keep us from all harm,

Tho’ thousands gainst us rise,

His buckler we must sure put on,

If we would win the prize.

Seven Danvers men were killed in and around Jason Russell’s house in Menotomy, so that town got the next mention—which the newspaper’s Essex County audience probably appreciated.

Eventually the poet got to individuals, naming a couple of men at the top of society—Capt. James Miles of Concord and Isaac Gardiner, Esq., of Brookline—and Benjamin Pierce of Salem, also killed at the Russell House. Other dead officers went unnamed, however.

Ezekiel Russell printed this poem at the bottom of his “Bloody Butchery of the British Troops” broadside, shown above. You can peruse that page more closely through the American Antiquarian Society, founded by Thomas.

The Russell broadside contained some errors (a missing “brave,” “young” became “your,” another “your” dropped out), suggesting that shop hastily copied the text out of the newspaper. I would have expected the transmission to go the other way: from the Russell print shop, which was known for publishing a young woman’s elegiac verses, to the Essex Journal.

That in turn suggests that Russell didn’t issue the “Bloody Butchery” broadside until more than a month after the battle. Maybe he needed that time to engrave all those coffins.