“Not a topsail vessel to be seen”

So I’m going back to mid-June 1774. Many of Boston’s merchants thought the top priority should be finding a way to lift the Port Bill, even if that meant (as George Erving and John Amory proposed) raising money privately to pay the cost of the tea destroyed in December.

The town’s political leaders, on the other hand, felt that standing up to Parliament’s oppressive laws was more important than regaining some expedient advantages in business.

The merchant John Andrews, who normally supported the Whigs (albeit at an ironic distance), joined their opponents on this issue. He saw the town’s economic situation as dire, as he wrote in a 12 June letter to a relative in Philadelphia:

Our wharfs are intirely deserted; not a topsail vessel to be seen either there or in the harbour, save the ships of war and transport, the latter of which land their passengers in this town tomorrow.Only five days after Andrews wrote, Gen. Thomas Gage dissolved the Massachusetts General Court, as recounted here. That legislature never had a chance to provide quarters for the troops in Boston—or to refuse to.

Four regiments are already arriv’d, and four more are expected. How they are to be disposed of, can’t say. Its gave out, that if ye. General Court don’t provide barracks for ’em, they are to be quarter’d on ye. inhabitants in ye. fall: if so, am determin’d not to stay in it.

Nonetheless, those soldiers were never housed in private homes, nor did Gage invoke the revised Quartering Act to put them into “uninhabited buildings” and taverns. Instead, the royal government built barracks and rented buildings from willing landlords, including warehouses empty because of the lack of trade.

Andrews still thought royal officials were being too strict:

The executors of the [Boston Port] Act seem to strain points beyond what was ever intended, for they make all ye. vessels, both with grain and wood, entirely unload at Marblehead before they’ll permit ’em to come in here, which conduct, in regard to ye. article of wood has already greatly enhanced the price, and the masters say they won’t come at all, if they are to be always put to such trouble, as they are oblig’d to hire another vessel to unload into, and then to return it back again, as they have no wharves to admit of their landing it on.Nonetheless, at this time Andrews saved his worst criticism for Boston’s zealous Whigs, “those who have govern’d the town for years past and were in a great measure the authors of all our evils, by their injudicious conduct.” Now those men were supposedly threatening to finish off the town’s trade with the Solemn League and Covenant.

Nor will they suffer any article of merchandize to be brought or carry’d over Charles river ferry, that we are oblig’d to pay for 28 miles land carriage to get our goods from Marblehead or Salem. Could fill up a number of sheets to enumerate all our difficulties.

TOMORROW: Back to town meeting.

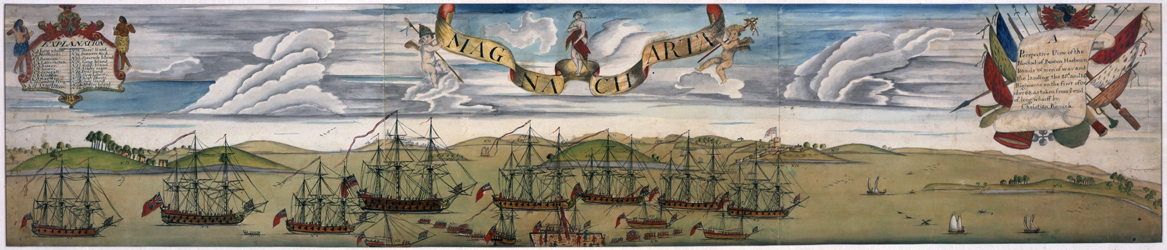

(The picture above, courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, is one version of Christian Remick’s painting of the Crown fleet in Boston harbor as seen from Long Wharf in 1768.)