When John Piemont Set Up Shop in Danvers

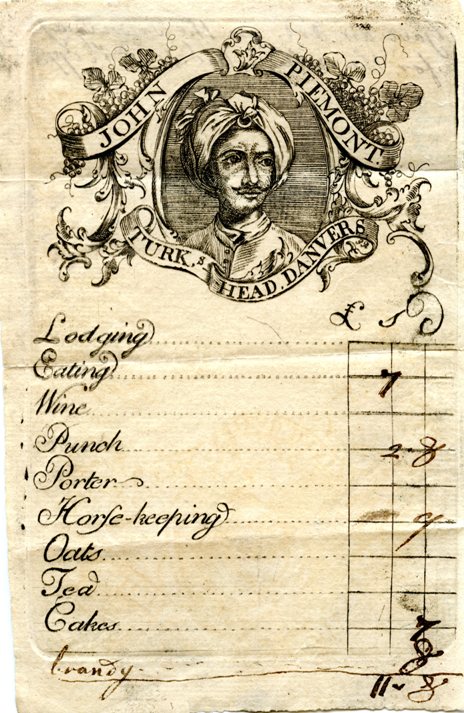

It involves the engraved billhead shown here.

It was the summer of 1969, and I was working for the local Historical Commission as a summer cataloguer and researcher, trying to put into order the thousands of town records. Most of the loose, individual town papers were enclosed in nailed wooden boxes as a result of a W.P.A. project in the 1930s when the records were roughly sorted into various departmental categories. The boxes had originally been used in food relief during the depression and were clearly, and to my eyes humorously, marked, “Dried Prunes–For Relief–Not to be Sold.” Unfortunately, the boxes were not good for storing manuscripts, and many of them had become nesting areas for all sorts of vermin. . . .To be exact, apprentices from the shop Piemont shared with another barber and wigmaker were involved in the first violence on King Street on the evening of 5 Mar 1770. One of those teens, Edward Garrick, criticized a passing army officer, and Pvt. Hugh White called the boy over and clonked him on the head.

Among these handwritten slips of paper, I noticed a very handsome item containing a fine engraving of the shoulders and head of a turbaned and mustachioed man with banners about him proclaiming, “John Piemont. Turk’s Head, Danvers.” The item was a trade bill of John Piemont’s eighteenth-century Turk’s Head Tavern, which was located on the old post road near what is now the junction of Pine and Sylvan Streets in Danvers.

Subsequent to discovering the identity of the trade bill’s printer, I learned from Dr. Richard P. Zollo, who wrote an interesting study on the life of John Piemont titled, “Patriot in Exile,” that Piemont was a Frenchman who settled in Boston in about 1759 and took up the trade of peruke [wig] maker. While residing in Boston, Piemont apparently became enmeshed in the patriot cause. He was a member of St. Andrew’s Lodge of Masons and was actively involved in the events leading up to the Boston Massacre of 1770. In 1773, partly as a result of losing Tory patronage at his wig shop, Piemont moved to Danvers and took on the management of a tavern.

There’s also a complaint from Pvt. John Timmins about Piemont and some other barbers clonking him on the head, as I quoted way back here. I still can’t make sense of this unmotivated attack, especially since Piemont’s business catered to royal officials and army officers. He even employed a moonlighting private, Pvt. Patrick Dines. I suspect Timmins came up with the complaint after the Massacre when he knew his superiors were eager for complaints about the locals whose names had come up in that dispute.

As Trask writes, Piemont later left Boston and opened a tavern in Danvers. When the war broke out in 1775, some locals “called him a Tory,” and the local committee of correspondence had to vouch for him. But back to the essay.

Months later, while browsing in a local book store I was looking through a book titled Paul Revere’s Engravings by Clarence S. Brigham. A plate in the chapter on trade cards caught my eye. A bill from Joshua Brackett’s “O. Cromwell’s Head” tavern on School Street in Boston, was reproduced. The design, format and size of this Revere engraving was almost identical to the Piemont bill that I had found.Check out Trask’s essay to see the clue that confirmed his suspicion that Paul Revere had engraved this image for the former barber from Boston.

I quickly looked in the index for “Piemont” and was referred to page 175, which stated that Paul Revere’s day book included many charges for engraving advertising cards and bill heads, but that no specimen remains of many of them. In June 1774 Revere made two hundred prints for a charge of 8 shillings to Mr. John Piemont.