“Twas Expected The Troops would have embarkd this night”

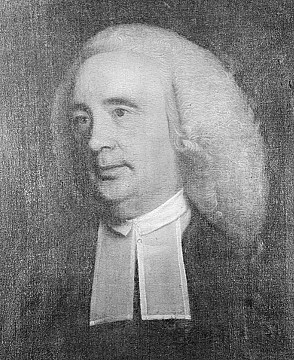

This night my Store on the Long Wharff broke open & almost A hhd of Sugar & A hog head of Ware Stole—Mary Hooper was the widow of the Rev. Dr. William Hooper (1702–1767, shown above), an Anglican minister Rowe admired. She was also the mother of the William Hooper who represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence.

Twas Expected The Troops would have embarkd this night but they still Remain in Town

I din’d at home with Genl. [James] Robertson Colo. Clark Richd. Green An Officer of the 5th Regt. Mrs. Rowe & Jack Rowe—

after dinner Capt. [John] Haskins gave me Notice that several officers were in Mrs. [Mary] Hooper’s House committing Violence & breaking Everything Left they Broke a Looking Glass over the Chimney which cost Twenty Guineas such Barbarous Treatment is too much for the most Patient man to bear.

“Rainy Weather” came on 16 March, and the preparations for departure went on.

The Troops are getting every thing in order to depart.There was a Boston paint merchant and official, about to evacuate, called Capt. John Gore for his militia rank. Just to make things fun, there was also a captain named John Gore in His Majesty’s Fifth Regiment of Foot. Rowe could conceivably have dined with either.

My store on Long Wharff broke open again this night—the Behaviour of The Soldiers is to bad—tis almost Impossible to believe it

I din’d at home with Mrs. Rowe & Capt. [John] Gore & Spent the Evening at home with Richd. Greene Mr. [Samuel] Parker Mr. [Jonathan] Warner & Mrs. Rowe & Jack.

Two officers of the 5th: came to Mee for Wine they wanted to be Trusted I Refused them since I have heard nothing only they Damned me & swore they would take it by Force—One of them nam’d Russell of the 5th. Regmt. the Other I dont know

As for Russell of the Fifth Regiment, no officer of that name appears in the Army Lists of 1773 or 1778. Then again, Rowe forgot the name of the officer from that regiment whom he hosted at dinner the day before. So he didn’t know them that well. Certainly not enough to extend credit for wine.

TOMORROW: The country people come in.