“Tell her to make her cheese a little salter”

Yesterday I recounted how Moses Gill, lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, gave a large cheese to John Adams as he assumed the office of President.

Gill sent the cheese late in March 1793 and advised Adams, “it will be in eating the first weake in may.” Adams told his wife before she set out from Quincy to Philadelphia, “it will last till you come.”

For years Abigail Adams had overseen a dairy on the family farm. She knew about making cheese. And in that regard, as in almost everything else, she had high standards. So how did she react to Lt. Gov. Gill’s cheese?

There’s no more mention of that particular cheese in the Adams correspondence. By the end of May Abigail was writing back to Massachusetts to ask for more cheese—but not from Gill.

Instead, on 24 May Adams told her elder sister, Mary Cranch, back in Quincy:

I will thank you to get from the table Draw in the parlour some Annetto and give it to mrs Burrel, and tell her to make her cheese a little salter this Year. I sent some of her cheese to N York to Mrs [Abigail] smith and to mr [Charles] Adams which was greatly admired and I design to have her Cheese brought here.Abigail Adams definitely wanted more cheese from Massachusetts. But she was hungry for cheese from local suppliers she knew, and she had particular tastes. We don’t know what Abigail thought of the cheese Gill sent, but we know she didn’t ask for more.

when she has used up that other pray dr [Cotton] Tufts to supply her with some more, and I wish mrs French to do the Same to part of her Cheese, as I had Some very good cheese of hers last Year.

After learning about this episode, I wondered if Gill told any newspapers about his gift. I found no coverage of this cheese in the Massachusetts press. It was a private favor between two gentlemen who had known each other for years.

That was quite a contrast to the next time someone from Massachusetts sent the President a large cheese. In January 1802, as described back here, the Rev. John Leland (1754-1841) of Cheshire presented Thomas Jefferson with a cheese to celebrate his becoming President the year before.

Cheshire was the exceptional Republican town in a Federalist county. Leland, leader of a Baptist congregation in a state with a Congregationalist establishment, supported Jefferson on the grounds of religious freedom.

Leland organized his community to produce a giant cheese for the new President. Their gift weighed 1,235 pounds—more than ten times the size of Gill’s cheese. Leland also made sure to tell the newspapers about that gift.

Jefferson, in turn, carefully paid for the cheese instead of accepting it as a perquisite of office. Even so, the Federalist press seized on this story, mixed in Jefferson's interest in recently discovered mammoth fossils, and harped on the President’s “mammoth cheese” for years.

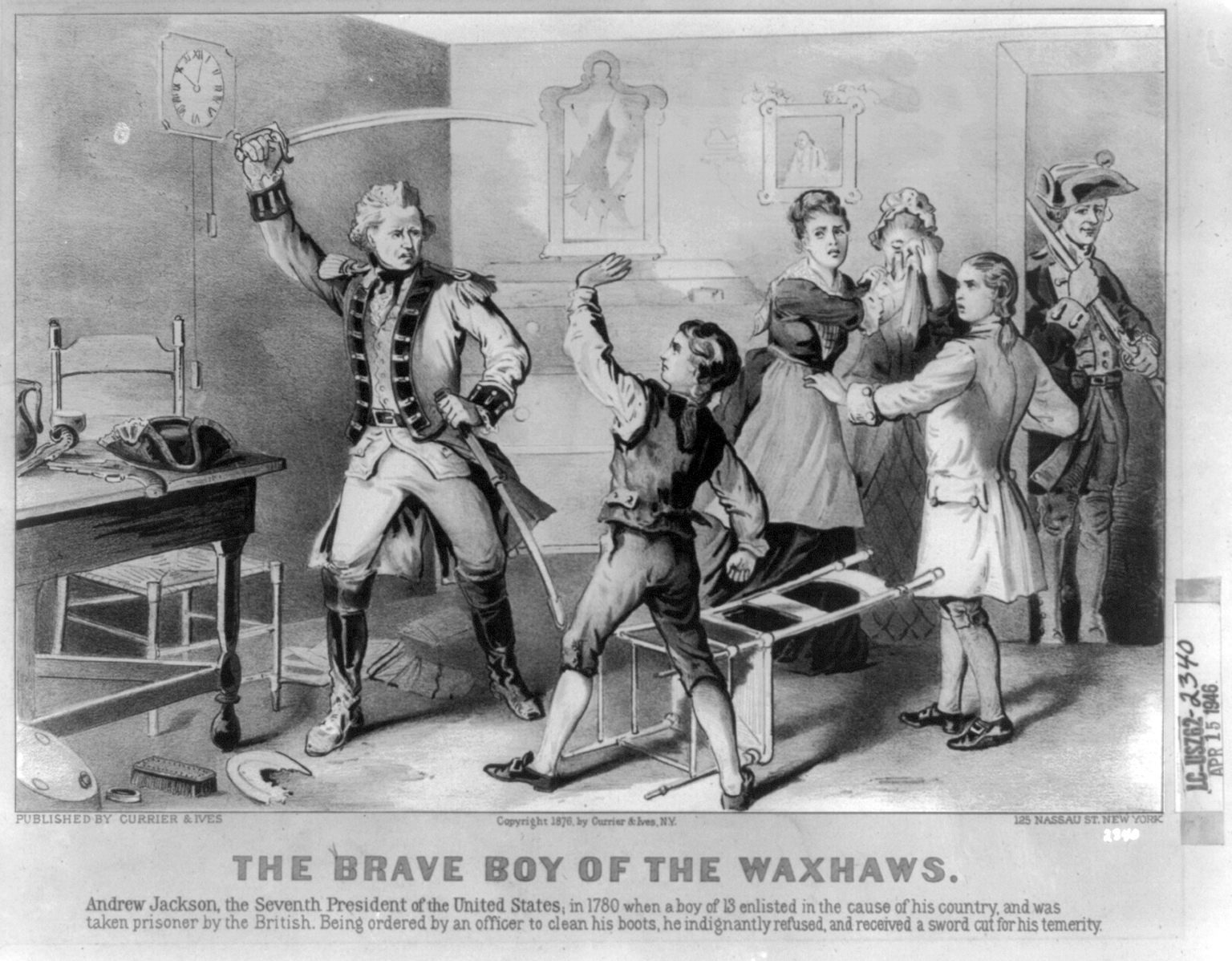

Indeed, the cheese for President Jefferson was so famous that in 1837 another set of cheesemakers sent a giant cheese to President Andrew Jackson.

In 1940 the Sons of the American Revolution erected a monument to John Leland in Cheshire. It includes a bronze memorial plaque about him and a replica of the cider mill used to press the mammoth cheese.

In June of this year, the Cheshire Community Association unveiled a replica of the giant wheel of cheese itself.