“Packed up his presses and types”

For his 1810 History of Printing in America, Thomas wrote a bare-bones version of this event. The 1874 reissue of that book included a descendant’s longer telling, drawn mostly from family lore but also citing that 1775 letter.

According to this account, early in 1775 Timothy Bigelow invited Thomas to start a Whig newspaper in Worcester. That would have been an addition to the Massachusetts Spy in Boston.

It’s not clear whether that venture had gotten anywhere beyond the talking stage, but it meant that Thomas had already thought about moving a press and type to Worcester.

Actions in Boston sped up that process. A mysterious note and a parade by the 47th Regiment threatened the town’s radical printers. Rumors went around that the government in London had told Gov. Thomas Gage to start arresting people. (It had, but the ministers wanted him to start with politicians, not printers.)

According to the 1874 account, Thomas ”sent his family to Watertown to be safe from the perils to which he was daily exposed.” It doesn’t mention that at the time Thomas was breaking up with his wife Mary because she had had an affair with Benjamin Thompson.

The later version continued:

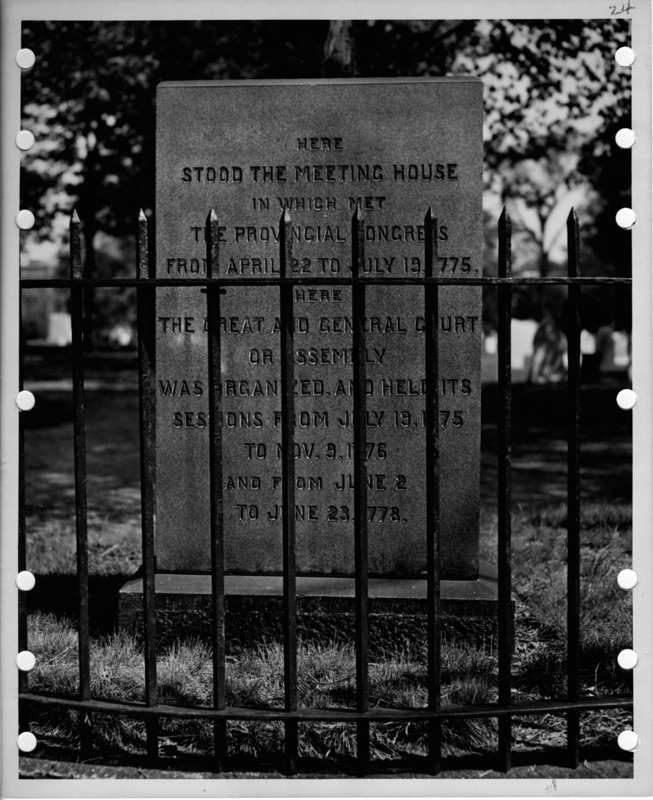

…his friends insisted upon his keeping himself secluded. He went to Concord to consult with Mr. [John] Hancock and other leading members of the Provincial Congress. He opened to them his situation, which indeed the Boston members well understood. Mr. Hancock and his other friends advised and urged him to remove from Boston immediately; in a few days, they said, it would be too late. They seemed to understand well what a few days would bring forth.Thomas was using his old master and partner Zechariah Fowle’s press, made in London in 1747. It remains today at the American Antiquarian Society, which recently celebrated the 250th anniversary of its flight from Boston.

He came back to Boston, packed up his presses and types, and on the 16th of April, to use his own phrase, ”stole them out of town in the dead of night.” Thomas was aided in their removal by General [Joseph] Warren and Colonel Bigelow. They were carried across the ferry to Charlestown and thence put on their way to Worcester.

Two nights after, the royal troops were on their way to Lexington, and the next evening after, Boston was entirely shut up. Mr. Thomas did not go with his presses and types to Worcester. Having seen them on their way he returned to the city. The conversation at Concord, as well as his own observation, had satisfied him that important events were at hand.

TOMORROW: Important events.