“Nathaniel Barber, Esq; Captain of the North-Battery”

He became one of the more gung-ho Whigs in Boston, though he didn’t hold significant political offices or (to our knowledge) publish political essays.

Barber married Elizabeth Maxwell in 1750, and the couple started having children the next year with Nathaniel, Jr. Barber probably worked as an ordinary merchant before opening his insurance office by 1762.

On 24 Sept 1766, Barber was in the crowd watching the Customs officials try unsuccessfully to search the warehouse of Daniel Malcom for smuggled goods. Not coincidentally, Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson reported that “Malcolm is a principal underwriter” of Barber’s insurance firm.

In two depositions after that event, Barber insisted that he had no idea who told him “that Upon Mr Malcoms House being attacked the Old North Bell was to Ring” to assemble defenders, and denied having passed on that rumor to magistrate John Tudor.

Barber also claimed that “from the appearance and behavior of the People assembled who were worthy Gentlemen and good sort of People, there was not the least appearance of disorder, much less Opposition to any legal Authority.” (The Customs officials didn’t see things the same way.)

Here are three notable mentions of Barber in the newspapers, starting with the Boston Gazette for 8 Aug 1768:

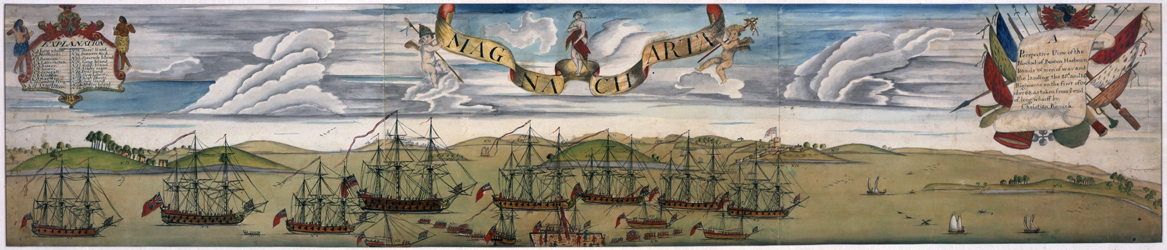

We hear that the Week before last was finished, by Order and for the Use of the Gentlemen belonging to the Insurance Office kept by Mr. Nathaniel Barber, at the North-End, an elegant Silver BOWL, weighing forty-five Ounces, and holding forty-five Gills.The silversmith who made that bowl was Paul Revere, and today it’s a treasure of the Museum of Fine Arts. The song was “The Liberty Song,” printed the month before.

On one Side is engraved within a handsome Border—To the Memory of the glorious NINETY-TWO Members of the Honorable House of REPRESENTATIVES of the MASSACHUSETTS-BAY, who undaunted by the Insolent Menaces of Villains in Power, and out of strict Regard to Conscience, and the LIBERTIES of their Constituents, on the 30th of June 1768, VOTED NOT TO RESCIND.—Over which is the Cap of Liberty in an Oaken Crown.

On the other Side, in a Circle adorned with Flowers, &c. is No. 45, WILKES AND LIBERTY, under which is General Warrants torn to Pieces. On the Top of the Cap of Liberty, and out of each Side, is a Standard, on one is MAGNA CHARTA, the other BILL OF RIGHTS.—

On Monday Evening last, the Gentlemen belonging to the Office made a genteel Entertainment, and invited a Number of Gentlemen of Distinction in the Town, when 45 Loyal Toasts were drank, and the whole concluded with a new Song, the Chorus of which is, In Freedom we’re born, and in Freedom we’ll live, &c.

In the 30 Apr 1770 Boston Gazette:

Yesterday se’nnight a Daughter of Mr. Nathaniel Barber, at the North End, was Baptized at the Reverend Dr. [Andrew] Eliot’s Meeting-House, by the Name of Catharine Macaulay. The same Gentleman about 18 Months ago had a Child christened by the Name of Oliver Cromwell, and about 18 Months before that, another by the Name of Wilkes.Edes and Gill’s newspaper had reported the christening of each boy, with a note that little Wilkes “had No. 45, in Bows, pinn’d on its Breast” at the ceremony.

On 1 Oct 1772, the Boston News-Letter reported:

His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to Commission Nathaniel Barber, Esq; Captain of the North-Battery in this Town, with the Rank of Major.You might ask why Gov. Hutchinson granted a prestigious rank to someone so obviously in the political opposition. In that period he was trying to use his patronage powers as commander-in-chief of the militia to peel men away from the Whigs.

COMING UP: Did that work?